Every country has its stereotypes. From Japan’s point of view, Americans are three things: loud, friendly, and generous. We talk too much, too freely, too familiarly. We’re kind to strangers, to everyone. We share our things without holding back, we help our friends when they ask, and offer when they don’t. We like to have big gatherings and get to know people.

It’s mostly pretty true, and it isn’t the world’s worst stereotype. For the most part, I didn’t mind fitting the mold. It was easy enough to say, yes, I like making new friends. I like eating those foods. I do complete this cultural ritual with my family.

What bothered me was not saying “I,” it was “we.”

Americans don’t say “we.” Yes, I do this thing, but my neighbor might not. It’s a diverse place.

Japan is too, they just on the whole pretend they aren’t. It’s more polite. And so the phrase “we Japanese” can be heard in any given conversation. “We Japanese” do this cultural ritual. “We Japanese” like eating these foods.

I spent hours explaining to students that in English, we don’t say that, and so in English, you must speak for yourself only. “We Japanese” might eat miso soup three times a day, but you actually hate it for breakfast, and it turns out that you forget to take off your shoes all the time, and you actually think Fuji isn’t that beautiful. You are an individual.

Adults didn’t like it, but kids latched on, and after five minutes I’d usually have a classroom full of children comparing the level at which they hated natto and really wanted to visit Paris.

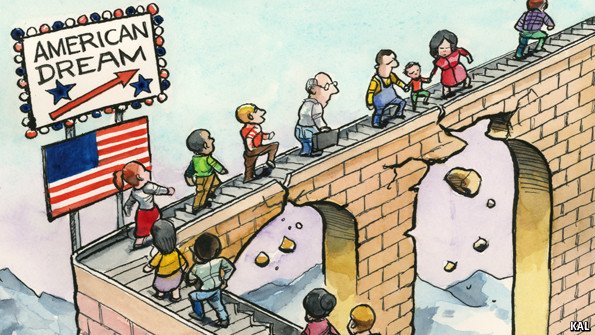

The American dream: 2.5 kids, house, car, job.

The dream of America…well, that’s what you make of it.

The Dream of America

The post office up the road from us is open twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. It might even be open at New Years, which is a bigger feat than anyone outside this country knows. It’s like saying that a Western company has been open every Christmas for the past hundred years—unheard of.

My fiancé delights in going there. I say delights; he drags his feet and looks annoyed and then comes back laughing about whoever they’ve got on staff. The girl who looks, no matter where she’s actually looking, like she’s staring at her feet. The man who has yet to raise an eyebrow no matter what country the parcel’s going to.

The parcels do go everywhere, and I mean everywhere. Antigua, Martinique, Kazakhstan, Brazil, the UK—if someone pays and the shipping is secure, my fiancé will send it. Our knowledge of geography is growing by the day. If there’s some sort of post office knowledge competition I’m sure our place will win first prize; for everything we send it is the staff who must look it up and confirm the address.

It helps here to mention that this is the main branch office for our ward and one of the largest post offices in the city. If we were to go to our actual nearest post office it would take fifteen minutes per parcel to send anything and they would feel the need to ask if we were certain we wanted to send the item internationally. As if we might say, “Oh, no, I didn’t mean to write 42 Wallaby Way Sydney, I meant Sendai!”

For all I know someone out there has done it and the post office really saved the day, keeping ba-chan’s jewelry or oku-san’s birthday present from great harm, but I doubt it.

Besides, and more to the point, if you’re mixing up Sydney and Sendai you have bigger fish to fry. I mean, really.

There is a place called gaikoku. It is a mysterious land, full of strange people with wondrous habits. They do funny things like wear their shoes in the house, and even chew gum in school! They speak a language called gaikokugo and eat gaishoku. It is a mysterious and unknowable place.

During my first homestay in university, the first thing my host family did was take me to the supermarket to make sure they had food that was okay for me to eat. Once there, my host mother, a kind, middle-aged woman with three children, asked what I liked to drink.

“Oh, anything,” was my reply.

No, no, she wanted specifics. She was that anxious. Coke? Coffee?

“I mostly drink water,” I said. It’s all I could think of.

She replied that she’d always thought Americans drank Coke for breakfast. Or coffee.

As much as the west doesn’t understand Japan, Japan doesn’t understand the west. We are terror incognita, XXX, the place where there be monsters. In return, we have an unfortunate habit to conjure up geisha girls and giant squid in our minds.

When my fiancé went in for the graduation ceremony at the junior high school he was working in, the head teacher remarked that my fiancé needn’t have dyed his hair for the event; black would have been okay. As if red hair, red eyebrows, and red eyelashes are surely not natural on anybody, not even pale freckly foreigners from Great Britain. Surely they couldn’t be!

We are gaikokujin, and we come from gaikoku. We eat strange foods and speak in strange tongues. We look different. We are different.

Appearances are very important here.

We found out that a giant wholesale store was opening in our city and set off to find it one Saturday. The place had opened on a Thursday, and we figured that by giving it two days, it might be a bit less crowded. This is what is known as a massive miscalculation.

After a pleasant forty-five-minute drive on the highway, we were then subject to a less-pleasant forty-five-minute traffic jam caused by the traffic lights outside the new store. After finally parking in an overflow lot, we had the unique and doubtful pleasure of a forty-five-minute wait in line to get a membership card for said wholesale store. One card each, with our names printed on the front, for which we paid a fee and they messed up our names.

You see, we made the mistake of each writing our first and last names, but when they saw my fiancé had a middle name on his ID, they insisted on him writing that as well, but mistook his middle name—written after the last name and first name—for his family name. And my family name as well, since they didn’t require me to show identification. And thus we both received shiny new picture-ID cards belonging to two foreigners we’d never met.

After that was one last forty-five-minute wait to actually get into the store.

All this time, while waiting and waiting in the hot sun and dull parking-lot scenery, I’d watched the people around me. They came out of the store in threes and fours and fives, whole families, baby and ba-chan included, each of them trailing a giant slice of pizza and an extra-large drink. The parents looked thoughtful, calculating how many more yen they could squeeze out of the family’s budget. The children only concentrated on the pizza, not even pausing their chewing to shove each other. Surely this was America, if nothing else: pizza slices bigger than your head and giant tubs of laundry soap, with packages of more cake than three boys could consume in a week. Surely this had to be the dream.

I felt the dream as we walked in. The shopping cart was bigger than our kitchen table, each shelf half the size of our apartment building. There were olives and cranberries and chocolate by the metric ton. Surely, if anything was a dream it was this, a dream of food that never runs out.

Japan is within living memory of famine. It’s easy to forget that sometimes.

I love this excellent