Japan is in a death spiral. Or at least that’s the impression you’d get if you read the headlines. Here’s a recent selection:

Japan Is Dying: All Work, No Sex Means No Future — CBN

The Numbers Behind Japan’s Sputtering Economy — New York Times

Japan’s Demographic Conundrum: Echoes from an Aging Nation — The Yale Politic

The force fueling this ostensibly macabre future is a peak in population growth. The Japan Chamber of Commerce and Industry warns that at the current birthrate, Japan’s population will fall by a third over the next 50 years to 87 million, with roughly 40% of citizens aged 65 and older. Even with the rosiest assumptions—including a fertility rate of 2.07 children per woman—Japan’s population will be shrinking.

.gif)

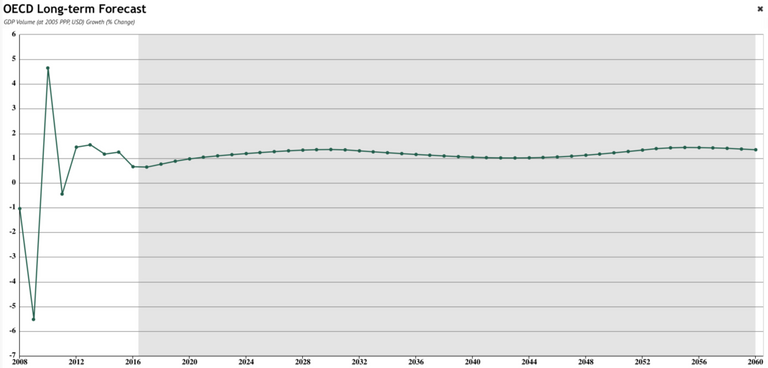

A falling population makes it difficult to continue growing the economy. The OECD projects Japan to grow its GDP (a general metric of an economy’s health) at around 1 percent a year, far below its annual average of 6 percent in the 1980s.

Economists often use increases in the size of an economy to gauge increases in the quality of life. With a sputtering economy, the numbers suggest disaster.

Many policy experts have grappled with ways to return to growth. The Japanese government recently instituted a three-pronged approach to fiscal stimulus by altering tax rates and government spending, manipulating interest rates and money printing, and rewriting business laws to motivate economic growth.

But what if our obsession with growth is outdated?

In her seminal book Limits to Growth (as well as the sequel), Donella Meadows outlines a reasonable theory: nothing can grow into perpetuity. The book’s focus is that the earth is finite. Growth in anything—whether it’s resource production, company sales, or global population—cannot continue without limit.

Researchers and academics have applied this theory to everything from peak oil to business management. The chief application, however, is population.

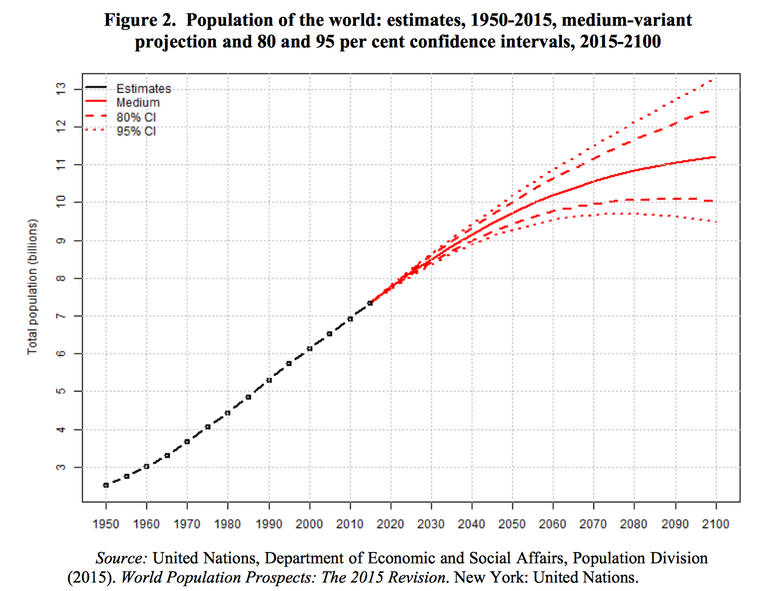

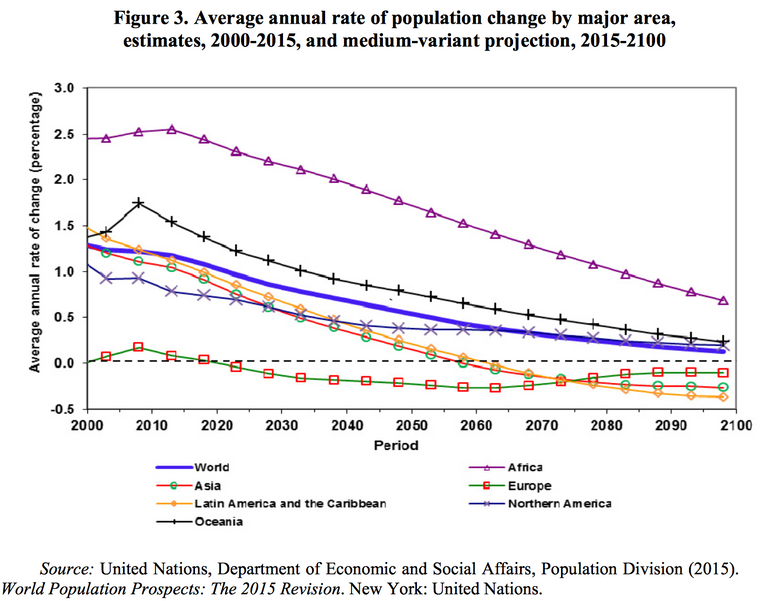

We’ve already discussed the future of the world. The conclusion is that “nearly every country will see progressively lower fertility rates.” Only rapid growth in regions such as Africa and Asia will keep the overall global population growing through 2100, albeit at a slower and slower rate.

According to Donella Meadows, this has to end at some point. Whether it stems from food production limits (more people results in less arable land) or increasingly unstable sanitation systems in urban areas (allowing the spread of cholera, dysentery, and typhoid), the growth explosion has to end at some point. And the United Nations thinks it will, around the year 2100.

While predicting the peak of a 1,000-year population boom seems speculative, most long-term data sets suggest it’s an inevitability.

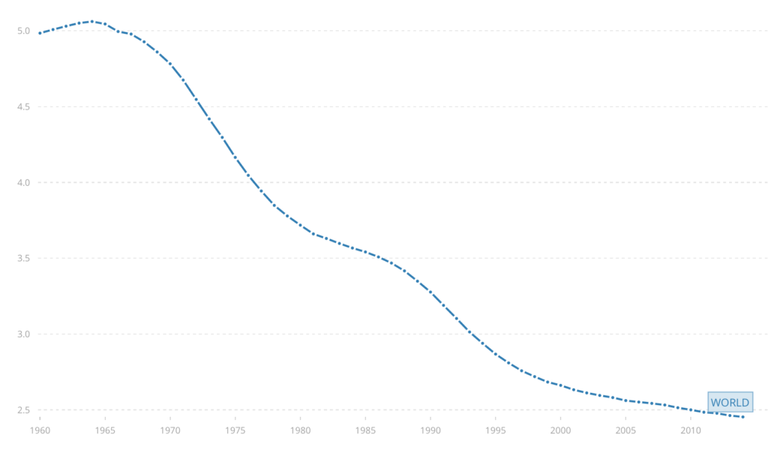

Research from the Population Research and Policy Review pegs the global fertility replacement rate around 2.3 children per woman, although in developed countries, this can be as low as 2.1 children per woman. What this means is that it takes a bit more than two children per woman to replace the parents and create a stable population. (The figure is higher than 2.0 due to various mortality and infertility factors.)

For over 50 years, fertility rates have consistently fallen towards this replacement level of fertility. After it falls below that level, the global population will begin to shrink.

According to the CIA, the total fertility rate in 2016 varied from 0.82 in Singapore to 6.62 in Niger. It’s places like Niger that have keep global population growth chugging along.

Research from The Review of Economics and Statistics show that, as incomes rise, fertility falls. According to Joseph Price, an associate professor of economics at Brigham Young University, “Richer countries have lower fertility rates than poor ones, and high-income families have fewer kids than low-income ones. ”

Thus far, global increases in incomes have caused fertility rates to freefall—and should continue to do so. But remember, even as Niger’s fertility falls, net growth remains positive until it dips below its replacement rate. That’s why we haven’t yet felt the last 50 years of fertility declines; global population won’t cross the magic fertility replacement level until around 2100.

According to Shihoko Goto, a Senior Associate at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, “The biggest enemy for Japan’s growth is Japan itself.” Put simply, it’s difficult to grow an economy when the country itself is shrinking.

But maybe a shrinking Japan—or a shrinking world—isn’t such a bad thing. A member of parliament from northern England is reported to have landed in Tokyo and remarked, “If this is a recession, I want one.”

The chief issue isn’t based in reality, but in the measurement of reality. GDP is increasingly a poor measure of prosperity. According to The Economist, “It is not even a reliable gauge of production.” Either way, the world is getting smaller, even if it takes time for fertility rates to reflect that. Economists, politicians, and academics will need to prepare for a different world.

Unfortunately, not only are they not replacing their populace, but their central bank has been by far the most profligate printer of fiat currency.

nice report bro keep it up