pointed out, there are very few (basically no) full-time entry-level jobs at history institutions. Everything is either part-time or requires several years of experience. However, I still need to eat and pay rent, so I’ve had to figure out how to sell my history degree to apply for other jobs.As I’m close to graduating, I’ve been doing a lot of job searching lately. But as my colleague @johnesmithiii

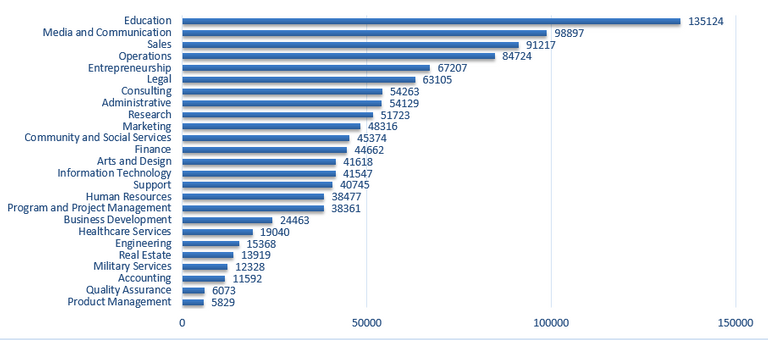

The primary skills I’ve been able to sell in applications are research, analysis, and report writing. These skills are valuable for a wide range of entry-level jobs. I can use my museum experience of researching and identifying unknown objects to showcase my research abilities. I can use my experience writing papers to demonstrate that I can conduct analysis and write reports. And I can use my experience as a tour guide to discuss customer service and presentation skills. However, I have found that it is much easier to tell stories from those internships and jobs in interviews demonstrating those skills than it is to tell stories of writing papers for school.

Of course, being an army officer gives me a whole other pool of experience and skills to draw from. While I was writing my resume, I was genuinely surprised at how many things I’ve done as a leader—it didn’t hit me at the time, because of how gradually the army increased my responsibilities, but I now realize I’ve actually done some pretty impressive stuff. Unfortunately, artillery skills don’t directly translate to any civilian job, so it’s taken a lot of work to explain my job in the army in a way that makes sense on a resume. However, I would find it difficult to build a solid resume for a non-history job with my history and museum experience alone, and I don’t envy the task.

What other ways could a historian sell their skills to a non-history employer?

Center for Public History and MLA Program, is exploring history and empowering education. Click here to learn more.100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History Initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment conducted by graduate courses at Temple University's

Oof! Talk about hitting it where it hurts. I've been really throwing myself into my Digital History class because I think one of my biggest selling points will be tech skills. Even having experience with something like Steemit and the related vocabulary to talk about blockchain is something I plan to take advantage of.

Sometimes I wonder if I should've become a computer programmer or IT technician. I took several programming classes in high school and built the family computer. I was always good at computer stuff. But, I chose to follow my biggest interest and here I am now. Even so, I know people who came in to the museum and collections fields from other careers, and perhaps I will be able to do that too.

history enrollments seem to be dropping.Thanks for bringing a real concern to the conversation @engledd. Perhaps this real concern is why

In a society that defines success through economic gains, the lack of correlation between history knowledge and earned income makes life hard for historians. Unfortunately, many of the benefits of a history degree seem to be "invisible" to employers.

I think the key is to have visible skills, such as web-design or accounting , and use those to get your foot in the door. Once you are in, your training as a historian will help you because you will have critical thinking skills and an open mind.

I agree. I rely on my military leadership skills to be my visible skills--telling a prospective employer on a resume I was chosen to be the second in command of 78 soldiers gives them an idea about what I've done in the army, and a launching point for discussing it in an interview. But I think most history majors don't have those visible skills, or if they do, they didn't get them through the degree program. Perhaps it's time to start rewriting history degree requirements, and including classes that provide visible skills. What if there was a history-accounting major that taught accounting skills alongside research, writing, and critical thinking? Or a history-business major? Or history-computer science major?

In graduate school, I was told not to worry, that worry does not make it happen. What does? Being in the right place at the right time. For me, that meant taking the first small opportunity that came along, a part-time, temporary job with no benefits. While in that, the job of curator opened up. While I wasn't their first choice, I did get the offer on the second round.

Hang in there.