3.3.3. The contribution of third-country innovation

-91. Europe has missed the “cloud computing” transformation. Today, SAP (at rank 7) is the only European firm having managed to climb among the top 10 cloud service providers by revenue, mostly on the back of its strength in enterprise resource planning.

-92. Europe has also missed the “Big Data” innovation wave, despite the legal and regulatory initiative of the “General Data Protection Regulation” (see section 3.1.1. above). In addition to protecting the EU consumers from having their personal data exploited by the big American internet platforms, a hope was nurtured that the legislation will provide a fertile soil for new business models and European innovation around the concept of “personal data stores” (PDS). A 2015 study estimated the potential market size for PDS providers in the EU to between 1 billion euro and 92 billion euro.

-93. GDPR had the noble goal of encouraging a fairer, more transparent distribution of the value created from data, between its rightful owners and those exploiting it. Today we can safely say that, if “data is the new oil”, GDPR had the undesirable effect of practically freezing “oil exploration” in Europe. It has increased the legal cost of collecting, storing and exploiting data for mutual benefit so much, that it de facto prevented a European data market from taking form. Five years after GDPR entered in force, a few European “PDS providers” do exist, such as the French “La Poste”, yet it is unlikely they generate even 1 billion euro of yearly revenues in aggregate.

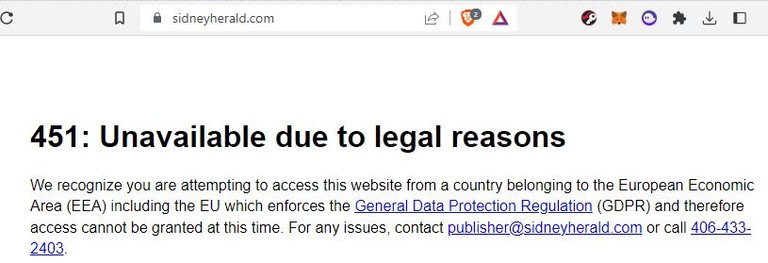

-94. GDPR has also disserved European consumers by making reputable yet smaller information sources inaccessible to them. Indeed, unable to shoulder the legal costs of complying with the regulation, some information providers from third countries decided they would rather prevent Europeans from accessing them (see Figure 8).

-95. At the same time, one would be hard pressed to point out a tangible effect of GDPR on the “balance of power” between European consumers and the big US internet platforms such as Google, Facebook and others. That technology-driven economics trumps hapless law-making and the intention of the legislator is best illustrated by the “Schrems” judicial saga.

-96. Maximillian Schrems, an Austrian lawyer and privacy activist filed a complaint in 2013 with the Irish Data Protection Commissioner (DPC) against Facebook. He argued that, in light of Edward Snowden's revelations about the activities of the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA), the data of EU citizens transferred by Facebook to servers in the U.S. was not adequately protected.

-97. The DPC initially rejected the complaint, citing the EU-U.S. Safe Harbour framework, which was agreed upon in 2000 and allowed companies to transfer data from the EU to the U.S. provided they adhered to certain data protection principles.

-98. Schrems appealed the decision to the High Court of Ireland, which referred the case to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). In 2015, the CJEU ruled in favour of Schrems, invalidating the Safe Harbour framework on the grounds that it did not ensure an adequate level of protection for the personal data of EU citizens.

-99. Following the invalidation of the Safe Harbour framework, many companies switched to using Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs) to legalize data transfers from the EU to the U.S. Schrems updated his complaint to challenge this practice, arguing that SCCs also did not provide adequate protection for EU citizens' data given the U.S. government's surveillance practices.

-100. The DPC again referred the case to the CJEU. In 2020, after the entry in force of the GDPR, the court ruled in what is known as the Schrems II decision. Although the Court invalidated the Privacy Shield framework, the successor to Safe Harbour, again due to concerns about U.S. government surveillance, it upheld the validity of SCCs in principle but emphasized that companies and data protection authorities have an obligation to assess whether the country to which data is being transferred ensures an adequate level of protection.

-101. Beyond the indubitable legal interest of these rulings, it is hard to spot any tangible benefit for the European citizens (or businesses) accruing from the outcomes of the GDPR. In its 2021 annual report, Facebook listed the on-going legal and regulatory uncertainty as a business risk, stating that “If a new transatlantic data transfer framework is not adopted and we are unable to continue to rely on SCCs (standard contractual clauses) or rely upon other alternative means of data transfers from Europe to the United States, we will likely be unable to offer a number of our most significant products and services, including Facebook and Instagram, in Europe.”

-102. Despite the bluster of European politicians claiming that “we would live very well without Facebook”, given the hundreds of millions of Europeans consumers using and relying on Meta’s products and services for several hours a day, every day, it is likelier that both European decision-makers and legislators would face a serious public opinion backlash if that risk came to materialize.

-103. Furthermore, Facebook reported in 2020 that there were over 160 million businesses using its suite of services worldwide, including Facebook and Instagram. Given their prevalence, it is likely that a significant number of these are in Europe, and a subset of those, probably in the thousands Europe-wide, from restaurants to small clothing retailers, would be small businesses that rely on Facebook and Instagram as their main or only online presence. Billions of euros or more would be lost if these services were not to be available anymore, and livelihoods would be endangered. Consequently, that two ministers of the Union's biggest countries, one of which is in charge of the economy, would make such declarations calls into question their responsibility and stewardship.

-104. In the introduction to this Chapter I was asking who the “gold miners” would be and whether they would come. I argued above that, despite much gesticulation, GDPR did not manage to strike the right balance and does not really protect EU consumers but was instead effective at preventing the creation of “data wealth” in Europe. If the GDPR experience is anything to go by, the cost of complying with MiCA could markedly suppress the emergence of innovative European start-ups in the field of blockchain technologies and crypto-assets.

-105. With the incumbent financial firms positioned to benefit financially from crypto activities, and with the EU consumers being “fair game”, the first to arrive are likely to be the big global CASPs such as Binance, Coinbase, Crypto.com, etc. These companies already serve large numbers of European customers and MiCA’s Art. 61 on “reverse solicitation” combined with “word of mouth” from existing customers will give them the freedom to continue doing so and patiently await the right moment before investing in Europe, while also offering them an incentive to engage with the regulators and try to shape the implementing standards to suit their business.

-106. It seems likely that these nimble, highly specialized non-EU firms will be responsible, whether directly or indirectly, for the bulk of blockchain and crypto-asset innovation, and that this innovation will therefore happen outside of Europe, thwarting the Commission’s strategic objective of having “strong European market players in the lead”.

-107. To sum up, MiCA appears to reproduce the approach of the GDPR and will probably have a similar outcome, in that blockchain and crypto-asset specific innovation will be pushed outside of the Union and left to companies based in third-countries. These will then come to utilise ancillary services from traditional European financial firms in order to sell their products and services to European consumers.

Concluding remarks

-108. In Part 3 I stepped back from the focused analysis of the legal text of the previous part and instead looked at the regulation in a larger context. MiCA appears as a pragmatic piece of legislation with a clear mission. Despite the length of time it took from the original Commission proposal of September 2020 to the final version endorsed by the Council in May 2023, it still comes across as a hasty affair, based on insufficient hindsight and a shallow understanding of the domain.

-109. MiCA uses boilerplate provisions that ignore the particularities of the technology and bears signs of considerable influence from the innovation-averse incumbent firms whose rents are at risk. Yet at the same time, MiCA legitimizes crypto-assets and erects a standard to which the actors of the industry can be held, thus contributing to quelling the controversies to which blockchain and crypto-assets gave rise. MiCA’s mere existence is expected to encourage both private and public institutions to experiment with crypto-assets and with enterprise blockchain systems.

-110. At the same time, given the similarities with the approach towards data protection, it is expected that MiCA will considerably suppress European start-up innovation in this domain. Instead, it will invite non-European, third-country firms to come and interface with European traditional financial entities in order to serve the European market. Unlike Patrick Hansen, who writes that “MiCA’s practical success boils down to the implementation standards and enforcement practices to be developed by the EU supervisory authorities in the next 12-18 months”, I do not think that any expectation on the side of ESMA, EBA and national competent authorities is warranted. Their mission is centred on risk reduction above all, and they are no friends of innovation. MiCA’s shortcomings are political at heart, and cannot be corrected by implementing technical standards.

-111. I would advance that blockchain and crypto-asset innovation will nevertheless happen in Europe too, if not where it is most expected and visible, but rather in the “middle offices” and “back offices” of a new activity sector which this regulation frames in the European body of law.

[223] CJEU, 6 Oct. 2015, Maximillian Schrems v Data Protection Commissioner, C-362/14

[224] CJEU, 16 Jul. 2020, Data Protection Commissioner v Facebook Ireland Limited and Maximillian Schrems, C-311/18

[225] S. Shead, “Meta says it may shut down Facebook and Instagram in Europe over data-sharing dispute”, CNBC 2022

[226] P. Davies, “Meta warns it may shut Facebook in Europe but EU leaders say life would be 'very good' without it”, Euronews 2022

[227] P. Hansen, “The EU's new MiCA framework for crypto-assets - the one regulation to rule them all”, op. cit.

Wow

I wonder how many accounts that are created on Facebook. Having 160million businesses is a lot. I’m sure those people must be paying for sponsored ads and all which will even help Facebook to earn more

Yes, but then it's a two way street: many small businesses would not be able to afford a web presence if it wasn't for Facebook

Congratulations @sorin.cristescu! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain And have been rewarded with New badge(s)

Your next target is to reach 160000 upvotes.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPCheck out our last posts:

E U ' is trying their possible best though

The European to an extent is trying to push everything to make sure all things work together

I am not against crypto regulation. The important thing is that they let us breathe in Italy. Now here we are full of taxes to pay. At least they charge us little on cryptocurrencies

Taxes are a national competence, not regulated by the EU. It is your Italian government that taxes you, not the EU