Democracy and dictatorship

We, in the "Western world", live in democracies. Political democracies. While the political systems of the big G7 countries are all slightly different, there are some fundamental common points:

- Pluralism of opinion reveals the existence of a spectrum of different governing paths

- Every person has one vote; elections are organized at regular intervals, where voters get to boot out the incumbent government if they weren't happy with its performance, and express a general preference for the next government, on the basis of non-binding promises.

The only reason why this makes sense is that governing implies compromises and trade-offs. No government can make everybody happy. Despite our wishes, we cannot "eat the cake and have it too." Or to quote a scientific paper, "perfect solutions are likely not to be available, and that the choices made by societies and/or political actors have consequences in the form of serious and unavoidable opportunity costs." (Landman and Lauth, "Political Trade-offs: Democracy and Governance in a Changing World")

As Nobel-prize winning economist Douglass C. North was writing, "In a world of uncertainty, no one knows the correct answers to the problems we confront […]. The society that permits the maximum generation of trials will be most likely to solve problems through time." ("Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance", p. 81)

The democratic process, whereby different political directions are proposed, selected, tried and assessed by the electorate, and discarded if deemed inadequate, is what confers our Western societies the "adaptive efficiency" they need to move forward. To illustrate that, Romania, a country I know, has changed 26 different governments in the 34 years since it overthrew the communist dictatorship of Nicolae Ceausescu, back in 1989.

We need political democracies because governing involves trade-offs and compromises ... we cannot "have our cake and eat it too" ... but we need to be able to decide together whether doing the former or the latter.

Dictatorships by contrast do not permit the electorate at large to reject a political doctrine in a structured manner. Yet that doesn't mean the people do not have a say at all. Witness recent-day China: despite not having a democratic process that would allow it to put other actors in power, the Chinese people were able to express their dissatisfaction with the "zero Covid" policy of their government. Those in power took the cue and changed tack, while remaining at the helm.

Thus even with "undemocratic institutions", changes in policy can be driven by the reactions of the governed.

Politics and finance

Besides the political democracy, it is worth taking a look at how decisions are made in the financial world, especially with respect to monetary policies. China, for instance, is not only a political dictatorship, but also a financial one: the Chinese people have no say at all in what currencies they can use for their economic transactions, and the policies governing the chinese yuan are crafted by the state apparatus under direct guidance from the very top of the political hierarchy, which controls the financial hierarchy.

In the Western world, the relationship between the political and financial hierarchies is less clear and more fluid. At times, it might even seem that, unlike in China, the financial hierarchy controls the political one.

It therefore matters to answer the question: we, in the Western world, live in a political democracy, but do we live in a financial democracy as well? And if that is not the case and indeed the (autocratic) financial hierarcy controls the political hierarchy, isn't it all somewhat of a farce?

Not that an outright dictatorship like in China would be preferrable, far from me that idea. But having a financial system where the preferences of the citizens are first collected, then acknowledged and third, taken into account (when possible), might lead to an increase in the prosperity and well-being of the greater number.

Financial technocracy

"But it isn't that already the case?", you might ask ...

Let's take a closer look: financial decisions are taken by National Central Banks (NCB) like the Fed in the US, or the Bank of England in the UK (BoE). In the Eurozone, the NCBs have pooled their sovereignty into the European Central Bank (ECB). The decisions are taken by the Chairman / President / Governor and the "Governing Council" (or whatever name it happens to have). Jerome Powell for the US Federal Reserve, Andrew Bailey for the BoE, Christine Lagarde for the ECB.

From top left to low right Jerome Powell, Chairman of the US Federal Reserve, Christine Lagarde, President of the ECB, Andrew Bailey, Governor of the BoE, and Kazuo Ueda, Governor of the BoJ, source: Wikipedia

These persons are not elected, which is probably just as well - if they stood for elections, rather than being competent they would need to be persuasive in order to convince voters to elect them. Instead, they are nominated, generally for a fixed term, sometimes renewable, by the elected politicians, and then allowed to do their job according to a mandate, independently from the politicians.

Note first that we are discussing here a "governance spectrum". The President of the ECB is nominated for an 8 year non-renewable term. In contrast, the Chairman of the US Federal Reserve serves a 4-year term but can be renewed indefinitely (Bill Martin: 1951-1970 and Alan Greenspan: 1987-2006 both served more than 18 years). The Governor of the BoE is nominated for a mandate of variable length which tended to last between 7 and 10 years in the past half century.

One extreme I am aware of is Mugur Isarescu, Governor of the Romanian National Bank (not in the Eurozone) which has served since 1990 with only one year of hiatus (during which he was Prime Minister). At 32 years in this post, he is arguably the most powerful person in the country, despite never standing for elections. Should such a powerful position be left to one person for an indetermined period?

Romania might have joined the euro like Croatia has, but for Mugur Isarescu, who holds the record for the "longest-serving governor of a NCB" since 2009 already, and who obviously doesn't think much about "pooling sovereignty". But what do Romanian economists think about that? Or, for that matter, the Romanian people? Fiercely independent, M. Isarescu doesn't need to take any of that into account and can happily continue controlling the Romanian Leu (note pictured) while shrugging the nominal EU Treaty obligation to "work toward joining the euro" (sources: Wikipedia, Club of Rome)

It is important to note that elected politicians are expected not to interfere with the policies of the Central Bank, whose independence is now an almost sacrosanct principle. So unlike, say, the national Security Services, the NCBs have, structurally, no democratic oversight. The ECB President is overseen by the Governing Council which is composed of the Presidents / Governors of the Eurozone NCBs ... so (s)he is responsible to a group of people who are themselves democratically unaccountable. Thus the Romanian NCB Governor Mugur Isarescu has served longer in the position than the Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu.

Monetary policies are decided by Central Banks that are fiercely independent and democratically unaccountable

That is somewhat understandable, you might say:

- First the institutions they lead have a mandate: "price stability and full employment" for the US Fed, just "price stability" for the ECB

- In fulfilling their mandate, they follow the best theories in the economic sciences.

In other words, these are technocracies, because following science is not a matter of choosing between different governing paths like in politics. Or, to quote a former British Prime Minister (Margaret Thatcher) and a former German Chancellor (Angela Merkel), who both used this formula several times during their mandates, including when making financial decisions, "there is no alternative" / "Alternativlos"

Indeed, "deciding democratically" whether 2 + 2 = 4 or 5 is obviously absurd, just as no people can "democratically" decide to abolish gravity or opt for H2 and O2 to combine into something else than water.

Deciding democratically whether 2 + 2 = 4 or 5 is obviously absurd ... but economics is not mathematics

The "dismal science"

Except ... except that economics and finance are no mathematics. Economics, a science for which you'll find a wide range of definitions (including "the study of decision making for allocating resources under conditions of scarcity") is also nicknamed "the dismal science". It is neither physics nor chemistry. Theories which used to approximate economic phenomena relatively well in the past had to be ditched and consigned to economic history books because they proved unable to account for how more recent events unfolded.

Let's take for instance inflation, a phenomenon which has occupied the economists since as long as their discipline exists, and which appears explicitly in the mandate of most Western Central Banks. The current orthodoxy is that to fight inflation, NCBs' main (or only) tool is to raise interest rates. This has worked often, yet it has not always been the only admissible tool (at least theoretically). Back in '70, Nobel-prize winner Friedriech Hayek proposed a different way to fight inflation, by removing the monopoly of money from the Central Banks and allowing a competition in currencies.

Even today there are serious economists such as Lawrence H. White and George Selgin who argue convincingly that giving Central Banks a strict monopoly on money creation might not maximise economic value creation and general welfare.

There are choices in policies, but are there also choices when discussing monetary policies?

That means that, like for other policy areas, even when it comes to monetary policies, it might be time to revisit the orthodoxy of the past 50 years, and inquire whether we shouldn't come up with a genuine mechanism for taking into account the democratic will of the people, or at the very least the diversity of economic theories?

Practical choices in monetary policies in the era of crypto

What changed lately, so as to warrant a reconsideration of an institutional arrangement that has served the Western world quite well for half a century? As it happened in so many other areas, an unstoppable technological upswell has reached monetary policy. It is currently manifesting itself in the flurry of monetary innovation that has followed Bitcoin.

Whereas the US still tries to regulate Bitcoin and crypto on the basis of existing, century-old securities laws, while mulling an update of the legislation, the EU has rushed to legislate and issued this year Regulation (EU) 2023/1114, aka "MiCA" ("Markets in Crypto Assets")

It is essential to keep in mind the opening "Recitals" of this brand new legislation. You can read them in the image above but they are so central that I'm also going to underline here the main points:

"(1) It is important to ensure that Union legislative acts on financial services are fit for the digital age, and contribute to a future-proof economy that works for people, including by enabling the use of innovative technologies. The Union has a policy interest in developing and promoting the uptake of transformative technologies in the financial sector, including the uptake of distributed ledger technology (DLT). It is expected that many applications of distributed ledger technology, including blockchain technology, that have not yet been fully studied will continue to result in new types of business activity and business models that, together with the crypto-asset sector itself, will lead to economic growth and new employment opportunities for Union citizens."

Keep in mind expressions such as "enabling the use", "promoting the uptake", and "new types of business models" ...

"(2) Crypto-assets are one of the main applications of distributed ledger technology. [...] When used as a means of payment, crypto-assets can present opportunities in terms of cheaper, faster and more efficient payments, in particular on a cross-border basis, by limiting the number of intermediaries."

Again, keep in mind the direct implication that "limiting the number of intermediaries" appears as a good, desirable thing ... But who are the current intermediaries and why are they needed, when a new technology such as DLT is absent? Are the "credit institutions" (i.e. banks) intermediaries in today payments? If so, should one infer that MiCA's recitals look approvingly on the possibility that crypto-payments could perhaps do away with the need for "credit institutions" to act as payment intermediaries?

Preventing Union citizens from taking advantage of new business models

If you were to, understandably, infer precisely that, you'd be taken aback by subsequent Recitals of the same piece of legislation which appear to frontally contradict the spirit of the first two recitals quoted above.

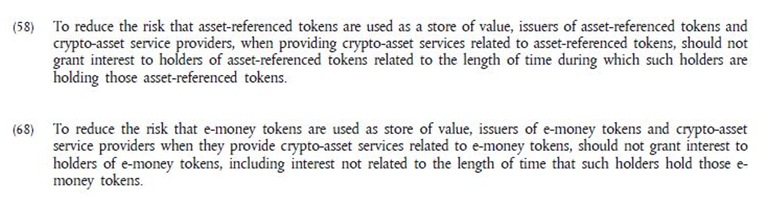

Indeed MiCA classifies crypto-assets in three broad categories. The ones best suited for payments are those commonly called "stablecoins", but which MiCA chooses to split in two different types, "asset-referenced tokens" (ARTs) and "electronic money tokens" (EMTs) for reasons which can be imagined but are not made sufficiently clear.

Under heavy, irresistible influence from the incumbent banks as well as the democratically unaccountable ECB, which is obviously protecting its own power, MiCA bluntly forbids EU-based stablecoin (whether ART or EMT) issuers and service providers from paying any type of interest to holders of stablecoins (see Recitals 58 and 68 below, as well as Articles 40 and 50 of the Regulation).

This equates to a mortal blow to these types of crypto-assets as they are put at an artificial disadvantage with respect to bank money, on which banks are free to pay interest. If the Union really wanted to "enable the use of innovative technologies", and get Union citizens to "enjoy the benefits of faster and more efficient payments", it would logically first need to encourage Union citizens to have stablecoins in their wallet to begin with. One can hardly pay with something it doesn't have ... But who in their right mind would bother acquiring these crypto-assets by exchanging bank money - on which one gets interest - into stablecoins - on which granting interest is forbidden?

I would like to remind here the words of Patrick Hansen which I quoted in a previous post:

The current proposed EU rules for crypto (MiCA) will effectively suppress EURO-denominated stablecoins even before the emergence of this market.

If the EU wants the EURO to play a major role in the future of global payments, stifling EURO-backed stablecoins is literally the opposite of what should be done.

The justification for this shockingly innovation- and technology-adverse, illiberal policy is incredibly flimsy: "to reduce the risk that [these tokens] are used as store of value"? Is that even a risk ? Is it really a risk that needs to be reduced? Where is the evidence for those claims? The ECB is not obviously worried that gold, US dollars or real estate might be used as store of value ... Even if the stablecoins might arguably pose a greater risk, is the measure of totally forbiding interest proportional to the objective pursued?

Proportionality is an important test that all Union legislation has to pass.

The question is all the more relevant given the fact that Union citizens are otherwise free to invest in US-denominated stablecoins ... on which there is no restriction on paying interest (see image below, displaying an ad from Blockchain.com touting enticing annual returns on dollar-denominated stablecoins)...

It would thus appear that, when confronted to a new technological contraption, crypto "stablecoins", monetary policy principles diverge between the US and the EU: while the US Fed does not appear preoccupied about "the risk that stablecoins are used as a store of value", the ECB is very much worried ...

Yet neither has any mechanism to find out in a structured manner what the people (or even trained monetary theorists) think about this specific trade-off. Not that their statutes would need them to care about anyone's opinion either ...

At present the question is moot, as no one is entitled to challenge the will and decisions of the NCBs, even if these decisions are, from one NCB to another, clearly at odds, thus indicating we have left "technocratic" grounds, and are actually witnessing unelected, unaccountable institutions making political choices for which they never received a mandate.

Yes, I know what you'll say: "this is a legislation that has been created by the EU legislator" - which does enjoy a veneer of democratic legitimacy - "NOT by the ECB!" But that claim is so obviously a shameful fig leaf that I can't even bring myself to refute it. Suffice to say that the prohibition of interest has been incorporated following consultations with the incumbent banks (which did not like the idea of being "desintermediated") and with the ECB.

Conclusion

I call hereby on our political and financial masters to reckon that blockchain technology and crypto face our institutions with a much bigger challenge to existing governance arrangements than it has until now been acknowledged.

That an in-depth rethink of the institutional architecture is called for. That, among others, monetary policy is not mathematics nor physics. That in the era of crypto, monetary policy faces trade-offs and choices, such as the one illustrated here: whether to allow stablecoin issuers to grant interest to their holders (and run a theoretical risk, for which the evidence is scant at best) or not (and forgo economic growth and employment opportunities).

And that therefore the consensus of entrusting a monopoly on monetary policy to a pure, democratically unaccountable technocracy (a Central Bank) as we have done with undeniable succes for half a century, might have outilived its usefulness.

Entrusting a monopoly on monetary policy to democratically unaccountable technocracies (the Central Banks) has served us well, but in the era of crypto, it might have outlived its usefulness

Bitcoin and crypto have created an alternative to our financial system. Granting interest is just one among many other choices and trade-offs which have appeared as a consequence of the crypto alternative. Faced with alternatives, some decision makers will take decisions which, in hindsight, will prove good, while other decision makers will make choices that will harm the well-being of the citizens. The people should have the right to show the door to the latter and replace them. In the current system, this is not possible.

After quietly surpassing the length of the reign of the reviled political dictator Nicolae Ceausescu, gentle and soft-spoken financial autocrat Mugur Isarescu can continue improving on his record of "longest serving Governor of a Central Bank" year after year, while watching elected politicians come and go. And no one can trully challenge him or even question him about the cost to ordinary citizens of "Romania not joining the euro" as it commited to, for instance, or any other questionable political choice he has ever made.

Can we then still say that we are living in democracies?

Thank you so much for sharing your valuable incisive analysis!! I hope policymakers read it!

Yes, me too :)

Yay! 🤗

Your content has been boosted with Ecency Points

Use Ecency daily to boost your growth on platform!

Support Ecency

Vote for new Proposal

Delegate HP and earn more, by @sorin.cristescu.

Blockchain is already a challenge to government itself

I just feel we can do better. Thanks for the overview

Wise words and nice reflection