CHAPTER: 2

PART: 1/3

The summer of 1985 was memorable. The twelve-year-old was finally allowed to move into a room of her own. Not only had this long-awaited independence been granted, but my passion for performance was finally being channeled, as I had managed to bag a children’s show. Almost a year earlier, a female producer at the only television network, PTV, had spotted me in a stage play produced by my mother for a women’s charity in the Peshawar Club for the army. So impressed was Bushra Rafiq by my performance that she tracked me down and asked me in for an audition for a new puppet show she was launching on the state TV station. She had previously worked with the comedian, puppeteer and genius Farooq Qaiser. They needed a presenter for a children’s program.

Bushra had seen me play the lead role in full makeup and ball gown. When I turned up in a frock and a ponytail, she was taken aback. They had been looking for a young lady, not a child. I wasn’t even a very girly kind of girl. With an adoring older brother that I idolized, I was more likely to be seen with war paint on my face pretending to be Native American, fighting imaginary battles in the Wild West, rather than playing with dolls or experimenting with makeup. Nevertheless, she gave me a passage from a children’s storybook to read out and I read it my way. People say that when I tell a story, I do it not only with the voices of the characters, but with full expression and complete immersion. Bushra was very creative when it came to using talent, and she fought the TV bosses for me to get the presenter position.

When I turned up on the set, I was given a dupatta to wear on top of the dress I wore, and was then caked in makeup. I was twelve but looked a lot older. In fact, I didn’t look too different at twelve from how I would look at 44, but of course I lost the softness that the adipose layer gave me. I was a nightmare for the makeup artists as I hated makeup (especially eye makeup). I was an even bigger challenge for the PTV Urdu scriptwriters: I couldn’t read Urdu very well and the big words just sounded wrong, so I improvised. It wasn’t the prescribed Urdu for television. It was contemporary and anglicised, but the audience loved it. The catchphrase that became popular at the time was the result of me simply being my chirpy self on set. On the first day, the chief puppeteer (to keep me alert) sang out my nickname.

“Ms Reeeeeeeeeeeeema!” I smiled and immediately sang back ‘Jeeeeeeee haan’. It was only a playfully affirmative response; a simple elongated and melodious “Yes!” But it quickly became popular with audiences and developed

into something of catchphrase.

The long words and long recordings were not easy for a fidgety child, but the seniors kept me engaged with off-air gaffes and a constant stream of biscuits, a tradition which continues to this day. If you want Ms. Khan to stay chirpy, keep the biscuits coming! I had positive and protective encounters with the adults I worked with on PTV. I discovered that one of the producers, the late Farukh Bashir Sahab, was so fatherly that he kept all the fan mail away from me since most of it

was from boys. My mother would keep a hawk-like eye on the proceedings from the far end of the studio. She spent her entire summer chaperoning me, which I never realized or gave her credit for until much later. However, despite being a diligent and hyper-aware parent, she did not know that the risks to our children are far greater than we can comprehend. She perhaps felt that media was full of predators, so she was vigilant in TV studios. But in actual fact, abusers come in all sorts of guises.

Children in Pakistan are often sexually abused by home help, and it is still overlooked by lazy or status-conscious parents. Having a maid or a helper for your child is a symbol of prestige. Some slightly more concerned parents may employ older children to look after their young ones, and with no idea of the huge risk of not only accidents, but also of sexual exposure by those youngsters. The concept of paedophilia was alien to us while we were growing up. Often, our parents, in an effort to not pollute our minds, leave us unprotected to the dangers that we are exposed to as children.

My mother had always encouraged my performing abilities and, since I was a keen singer, she sent me for musical training at the established Abbasin Arts Council in Peshawar. It was a group activity with other children and several musicians in a hall. From all angles, it could be regarded as a safe activity. The unsuspecting, carefree nine-year-old, who was a confident performer and the daughter of the President of the Children’s Academy, was given preferential treatment by the boss. Everyone respected him. After all, he was an educated professional. I had been brought up with strict expectations of politeness and manners towards adults. To this day, that politeness is a burden, as I find it hard to get rid of people who may be boring me to death. I find it difficult to cut meetings short. But our children must be taught to NOT be polite if they feel uncomfortable.

There was something about this ‘Uncle’ which made me uneasy, but I could not fully comprehend what it was. After successfully evading offers of biscuits in his office, I was to discover why I did not like him on what is known as Iqbal Day. That day, our group was performing to a hall full of literary intellectuals at the Pearl Continental Hotel in Peshawar. The ‘Uncle’ came to get me from the ground floor, where we were all getting ready for the performance, and told me he was taking me upstairs to the hall as it was running late. He had brought me a bar of chocolate. I took the chocolate from the balding and ageing bureaucrat and walked with him to the lift. It was too short a walk to the lift for the nineyear- old to plan an escape. As we stepped into the lift, my sense of unease increased. As the doors closed, he asked, “Why do you think I like you so much?”

“Perhaps because you have no children of your own?” I responded. “Why, you clever little girl” he said The next 30 seconds would haunt me for years. He bent down, and I felt his mouth on my lips. The thought of it makes my skin crawl to this day. It was such an awful feeling that I have to physically shake the image from my head even as I recall it. The

image of that creepy man, with his afro-style frizzy hair at the back of his balding head, is etched into my memory. We need to tell parents and children that paedophiles come in suits too.

Fortunately for me, the lift opened on the first floor. It was a brief moment of violation that tortured me for years. I went on to perform in the tableau with not a step out of place, but I gave up my singing lessons forever. I did not know what had happened. I had no name for it, but I knew that it was very wrong and that I had to protect myself from it, and from him. I could not talk to any adult about it.

The shame of what had happened was too much to confess. I was lucky that I could choose where I wanted to go and put my foot down, but many children may not have that liberty. They may not be able to avoid their maths or religious studies lessons because of strict parents. Do they have anyone they can talk to?

As an adult, I would actively campaign for this, in any way I could. This deep desire to protect children was rooted in another change. In the summer of 1985, I discovered another trait of mine: how much I loved babies. My first baby was my first nephew, Abubakr Khan, who arrived in August. With him arrived my chance to be a parent, and it would seem parenting came naturally to me. We were waiting at home when we got the news. As we reached the hospital, I saw my brother-in-law, Khalid bhai, sitting on the stairs of the hospital. It seemed as if the tall man had shrunk. I put a reassuring hand on his shoulder and felt him shivering. I went upstairs and the doctor pointed out Abubakr to me. He was the baby with the oblong head, thumb sucking noisily. I immediately bonded to him. Nothing was difficult or scary for me. I took care of everything from clipping nails to giving him medicine.

Abubakr and I became inseparable over the years; he was the younger sibling I had so desperately wanted. It not only prepared me for single-parenting, but reinforced my identity as a mother early on in life. I would be blessed with seven nephews, all of whom I am extremely close to. Along with my three children, they make my core circle of friends to this day. We tend to hang out together, and I end up assuming the role of agony aunt, quite literally. People have often described me as ambitious, but my teachers always described me as noncompetitive. My goal in life was never to defeat others. I never cared who came first. What mattered more to me was achieving what I had set for myself, and moving forward as a person. I didn’t have my eye on marks; I cared more about reading the book from the beginning to the end. Knowing everything was my motivation. Unlike the other girls, I never memorized past papers and the pre-prepared answers within them. Instead, I understood what I was studying. I wanted to learn.

Running after material success leaves people empty and unhappy. The diamond ring you must have for your hand will only put distance between you and your friends and will never give you a nice warm hug. Unlike sportsmen, winning medals and positions was immaterial to me. I wanted to win genuine respect and love, hoping to have just a few people around me who I could laugh with over cups of coffee and cake. Be wary of sycophants: they are boring and will never give good advice. Power-hungry, egotistical people are only ever surrounded by even greedier subordinates, who will all jump ship the minute the one they are on shows signs of sinking. We, as parents and society, put too much emphasis

on achievement. We teach our kids that the love they receive is conditional: ‘Bring me a trophy and I will love you more’. My mother could be described as one of those parents, who wanted us to bring back medals. But it was my father’s quiet influence, expecting nothing more of us than to be good and happy, that crushed her long list of material expectations.

After my three-month stint on TV, I was nominated for ‘Best Child Star’ in the 6th PTV Awards. The award went to a three-year-old drama artist. She was the daughter of the famous TV star Laila Zuberi. Since I was not from a media family, it was great fun to rub shoulders with the TV stars we had watched from afar. While I looked around wide-eyed at the glamorous celebrities, my mother was focused on winning. I never understood her anger and disappointment at the result. I was secretly hoping to win of course, but not winning didn’t affect me much. In fact, I learnt an important life

lesson: that at times we really will want certain things or outcomes to go our way. But if and when they don’t, and time passes, we will almost always look back on them and smile at just how worked up we’d got ourselves. Because nothing really matters. One day, you might be desperately waiting for someone’s phone call or text. But with the passing of just a few months, you will realise that you managed to not only live without it, but also that whatever it was you were so hell-bent on getting (be it a person, job or anything else) probably just doesn’t appeal to you anymore. It is absolutely true that life has better things planned for you than anything you can imagine. The only condition is that you persevere,

preferably with a smile. Keep moving on from every disappointment with renewed hope, because things will get better. They always do.

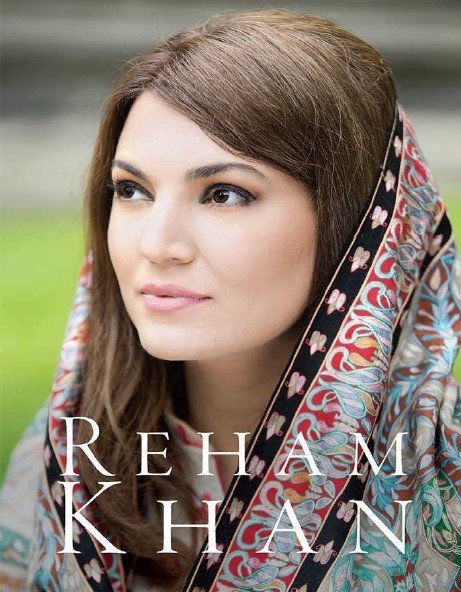

.jpg)

My brief stint on TV as a child star meant that I had more friends almost overnight. The preceding years had been dominated by bullying from classmates and patronizing comments from teachers. On one occasion, in year 5, I was embarrassed in class by Nadia for using the word ‘object’. She insisted that the word did not exist in English. Everyone laughed at me. I burst into tears, more upset at her betrayal. The teachers were another issue. One of the biggest problems was that they would show blatant favoritism towards kids of politicians. The Saifullah family dominated local politics and business at the time. However, the Saifullah girls were lovely and humble considering they were surrounded by sycophancy. I didn’t really think too deeply about it, but looking back, I was able to clearly see and understand how people’s attitudes could change when you stumbled across fortune and fame. I was a happy-go-lucky child, and quite a late developer, with no interest in boys or romance until much later in life. Other girls would talk about boys and use sexual innuendos in conversation, which I struggled to understand.

I was always pretty naive when it came to boys. One day on the TV set, a young boy I had just interviewed walked over from across the large studio and pretended to pick up a book from the coffee table on the set. Without looking at me directly, he whispered, “Hello, how are you doing?” Decent girls did not talk to boys in this kind of society. It was definitely frowned upon. I was taken aback and gave him my trademark raised eyebrow. He didn’t try it again. I didn’t really get it but my inner moral police didn’t like this covert behaviour much. My mother, for all her Westernised appearance, had given us very puritanical values, so I had a very uneventful teenage life.

Working on the TV series not only taught me discipline, but I learned to apply makeup early on. I became so good that I ended up doing bridal makeup for everyone in our social circle, and became a pro at waxing, eyebrow shaping and hair styling. My mum found it very annoying that I would be spending so much time and energy making others look good, while ignoring my own appearance. My best friend Nadia had golden brown hair thanks to her Danish mother, but since both of us had spent all summer in the pool, the chlorine had ruined her hair. Every day for a couple of months after school, I would put an egg mask on her hair. The careful approach paid off, and soon the whole of Peshawar was raving about her glorious mane.