We walked beyond toddlers

To see a section of it

A listless tribe thriving on pottery-doubts

And the broad-core of pinecone plantation

With irons under their feet

They trampled underfoot thorns on barefoot

We saw them scale walls to offset the agile greens

And into the farthest reached the deep to brave the wild barons

They return unscathed, untouched by the crippling swamp

Their spoils lighted fires that smothered deep into the moon

And there we sat bathing our teeth in fat and cooked blood

And there our minds lusted after our fading dreams

When we braved it to last, our seas brought to its shores

Creatures ironed to paper-size by thoughts

Which echoed

‘Crust of void beyond’

They paled to doom against the darkness our bodies unleashed

They were exotic creatures without skins even though they moved as we did

Our buttocks suck sounds and stuck

Amidst the mysterious phrases of the tales told by these femme fatales

But we dreaded to let loose the winds our bowels fought to keep

Their entrance nurtured our hatred

Even though we couldn’t resist their basic cunnings

They got us enrolled so we could be controlled

They ended it for us so we would be led like sightless yobbos

‘Enrolled’ meant to genuflect under control

For before you got enrolled, you might have been controlled

Either by sheer fun or dreary-fear

In our case the latter prevailed, caging our history’

They swarmed around our greenish fields

Like genetically-immutable bees, eating up our girlish faces

In pantaloons, they brought the clue of our nakedness…

‘I hate that literacy’

For we relished the moments when we saw shyness a slain, around naked creatures

31-MAY-2013

LITERARY APPRECIATION OF THE POEM, ‘BROAD DAY SLAVERY’

INTRODUCTION

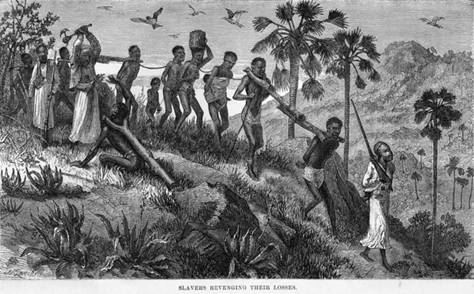

The poem ‘Broad Day Slavery’, written by Barnie Sarpong Freeman, is in all likelihood, about the theme of one recounting the intricacies of the slavery of Africans.

The eight-stanza poem written in free verse is about an expression of regret and frustration of a first-hand eyewitness (the persona) of the invasion of the whites and the exploits they wreaked on the people, somewhere in Africa. The poem recounts the oppression they (the native people) suffered as the Whites introduced to them a culture which sought to replace their most cherished native culture. It could be argued out that the time is set somewhere between the early 15th century and the late 18th century, in the time of Africa’s colonialism.

SUBJECT MATTER / THEME

The theme: An imposed slavery countervails the norms of the enslaved and oppresses their right to emancipation is derived from the subject matter: the complicacy and absurdity of an imposed slavery. The poet chose this sensitive subject matter to address the many forms of slavery that cripple and frustrate the progress of the enslaved. He takes his time to guide the reader through the stages of oppression they had to go through and the variety of native practices they had to abolish to pave the way to the new and exotic ones. The persona addresses the difficulty of embracing a new culture whose very operation and nature he disdains. He refers to this new introduction as ‘mysterious phrases of tales’ as reflected in line four of the fourth stanza.

STRUCTURE

The first three stanzas explain the account of the native people as they are seen ‘thriving’ in their land, exploiting and enjoying the many natural gifts nature endowed them with. The poem begins with an expression which seeks to illustrate the stage of growth the eyewitness (persona) is at with regard to the thought processes of man. ‘We walked beyond toddlers’, in stanza one line one, seeks to draw a link to the fact that the eyewitness was mature enough to have seen and kept details of the Whites’ invasion, placing a premium on the account he recounts next. The persona recounts the rest of the five stanzas, the nature of their suffering, and with his frustration, unleashes his regrets and anger on the system these foreign invaders introduced. His frustration is fueled by the thought that they (the native people) almost had it all before these ‘exotic creatures without skins’ invaded their land. This reflects in his tone in line one of stanza four and fuels the next lines to the closing stanza. He states: ‘When we braved it to last, our seas brought to its shores’. The poet uses enjambment in the first four lines (quatrain) of stanza one and an equivalent use in almost all of the stanzas except stanza five and the eighth stanza which are in a (quintain) form. The lines run-on into the next, giving the poem a river-flow and smooth transiency of reading.

DICTION AND STYLE

The poem is one that is written in a straightforward but complex language. It is predominantly in the simple past time, to suggest a simple and straight forward series of actions that took place when the Whites invaded these native people. The persona's choice of words for describing the frustration in a time of slavery (howbeit harsh) is appropriate. For clarity of atmosphere and setting, he uses everyday words like ‘greenish fields’, ‘seas… shore’, ‘plantation’. And to describe the complexities and absurdity of the slavery, the persona hides behind complex expressions like, ‘femme fatales’, ‘…genetically-immutable bees.’ The persona then puts it clear that the ideals, nature, and operations of the Whites were in sharp opposition to theirs by stating that, ‘They paled to doom against the darkness our bodies unleashed’.

The persona’s reflection on the slavery account exposes a weakness common to humanity; embracing change. when he states the last lines of the last stanza: ‘I hate that literacy’ and ‘We relished the moments when we saw shyness a slain, around naked creatures’, he emphasized his weakness to dealing with the change which the Whites introduced. ‘Literacy’ here implies that the persona was exposed to a system of change which sought to belittle his own by subjecting the latter to light and scrutiny, but he chose to ‘relish’ his own which he speaks of as one in the past; one done away with by these invaders. He states these last two lines of the last stanza which is subtly woven into the narrative to create a lasting impression of the static and resolved stands he places on his native practices against what the Whites introduced. The style is mostly descriptive but it appears as one narrating an event. So, the style follows after a descriptive narrative.

MOOD

The mood of the persona is filtered through the narrative as one of anger, hatred, regret, and frustration,

‘Their entrance nurtured our hatred’

The persona expresses his frustration where he cites an instance of a practice, which as young kids, they engaged in and were not harshly reprimanded or if there was a reprimand, a soft one. He continues by expressing his thoughts which seem to echo that they feared to engage in those practices in the midst of the Whites. A practice which was hitherto safe or somehow safe is no more convenient in the midst of these foreign invaders and their ‘literacy’:

‘Our buttocks sucked sounds and stuck

Amidst the mysterious phrases of the tales told by these femme fetales

But we dreaded to let loose the winds our bowels fought to keep.’

TONE

And the persona speaks with a harsh tone, one of discontentment, a as though he is in a perpetual dissatisfaction with the new trend of events

‘They got us enrolled so we could be controlled

They ended it for us so we would be led like sightless yobbos.’

The images the persona uses is intentionally placed to appeal to our senses of sight and touch in stanza two and three to draw us closer to his narrative forcefully.

FIGURES OF SPEECH

The poet uses figurative language to enhance the beauty of description and to create a better image. In line one and two of the last stanza, he uses simile to create a scene of how these invaders came in droves to inflict their culture on another’s and also to communicate how they chanced upon the most energetic of all that these native people had, despoiling everything and leaving nothing behind.

‘They swarmed around our greenish fields

Like genetically-immutable bees, eating up our girlish faces.’

PARADOX

He uses a paradox in the first two lines of the second stanza to paint a clear picture of the nature of the people that these invaders met; fearless and unashamed people content with their biological and material makeup,

‘With irons under their feet

They trampled underfoot thorns on barefoot’

HYPERBOLE

Line two of stanza three is exaggerated when the fires lighted, ‘…smothered deep into the moon’. With this statement, the persona states the merriment of the occasion when their brave ones return from hunting. They so enjoy their spoils; the game they bring home ‘…bathing our teeth in fat and cooked blood’ that their joy lingers deep into the night ‘…smothered deep into the moon’.

PERSONIFICATION

In line two of stanza three, ‘spoils’ is given a human’s attribute to light fire. Spoils is used out of its traditional sense to refers to the games they hunt in the wild. The spoils were good and tempting to be fed on. They were those that called for fires to be lighted.

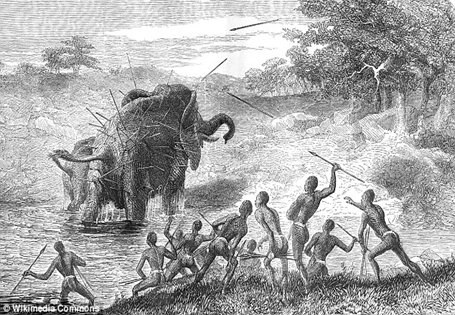

IMAGERY

This poem has solid imagery. The image of slavery, native culture, hunting, and gathering. That images are so revealing that not only is the reader sent back in time to brood on the colonial era but to also crave for the idyll life of the past when all was green and virgin.

SOUND PATTERNS AND RHYME

The poem is written in free verse, therefore, has no strict rhythmic pattern or specific rhyme scheme. However, it could be said that some words used in succession in some of the lines may have been deliberately chosen to enhance possibly, the flow and beauty of the poet’s intention and craft, as they form their own internalized rhythmic patterns, giving the poem a musical feel between the lines:

‘Tribe thriving’

‘…unscathed, untouched’

‘…sucked sounds and stuck’

‘They got us enrolled so we could be controlled’

‘For before you got enrolled, you might have been controlled’

Reading this poem, one needs to note the intensity that drives the persona’s choice of words in describing his native people (from stanza one to three) and when he shifts to commenting on the foreign invaders (from four to eight).

CONCLUSION

This poem could always pass as a good poem. It is worth reading for what it stands for. It represents the frustrations, suffering, and pain some people go through when their freedom is curtailed. And the effect some cultures have on others when there is a superimposing of one on another. It deals with a very sensitive subject; emancipation from slavery of all forms. The theme of slavery and the subject matter, the colonization of an African tribe by the Whites cast our minds to the time of colonialism and the impact it had on the people.

ENJOY THIS POEM