The voice on the other end of the phone was my Rolling Stone editor.

“What!?” I exclaimed, shocked out of my sleep.

“Turn the radio on! How quickly can you get to Seattle?”

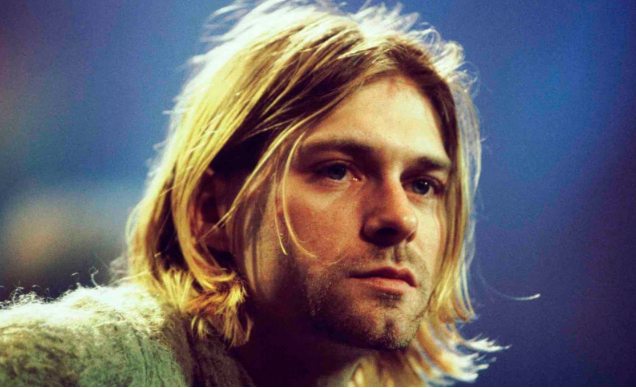

That day, I flew to Seattle to mourn the end of an era and the tragic loss of a life. Of an artist, a husband, a father, and a damn funny, sensitive, brilliant, tortured man.

I often think of Kurt today, in this time when the culture is standing up to bullies and bigots. He was a lone voice doing this a quarter century ago. And he was so much more.

This is the full, in-depth story of the circumstances leading up to his suicide. The original, shorter version won an ASCAP Deems Taylor Award for excellence in journalism.

This expanded version has never been published online before in its entirety. It includes a significant degree of additional reporting and research from after the magazine was published, as well as large sections that were cut for space.

On April 8, shortly before 9 a.m., Kurt Cobain's body was found in a greenhouse above the garage of his Seattle home. Across his chest lay the 20-gauge shotgun with which the 27-year-old singer, guitarist and songwriter ended his life. Cobain had been missing for six days.

Gary Smith, an electrician installing a security system in the house, discovered Cobain dead. "At first I thought it was a mannequin," Smith said afterward. "Then I noticed it had blood in the right ear. Then I saw a shotgun lying across the chest, pointing up at his chin."

Though the police, a private-investigation firm and friends were on the trail, his body had been lying there for two and a half days, according to a medical-examiner's report. A high concentration of heroin and traces of Valium were found in Cobain's bloodstream. He was identifiable only by his fingerprints.

Mark Lanegan, a member of Screaming Trees and a close friend of Cobain's, says he didn't hear from Cobain that last week. "Kurt hadn't called me," he says. "He hadn't called some other people. He hadn't called his family. He hadn't called anybody." Lanegan says he had been "looking for [Kurt] for about a week before he was found. . . . I had a feeling that something real bad had happened."

Mark Lanegan and Cobain.

Cobain's friends, family and associates had been worried about his depression and chronic drug use for years. "I was involved in trying to get Kurt professional help on numerous occasions," says former Nirvana manager Danny Goldberg, now president of Atlantic Records. It wasn't, however, until eight days after Cobain returned to Seattle from Rome to recuperate from a failed suicide attempt in March that those close to him realized that it was that it was time to resort to drastic measures. Cobain had gone "cuckoo," says a spokesperson for Gold Mountain Entertainment, the company that manages Nirvana and Courtney Love's band Hole.

Those who were friends with Cobain and his wife, Courtney Love, report an increase in domestic disputes during that period, including instances when Love was forced to spend nights away from the house in order to escape Cobain's erratic behavior. Cobain had even told a few friends that he was worried Love was having an affair.

His relationship with Nirvana was just as rocky. In fact, Love told MTV that Cobain said to her in the weeks after Rome: "I hate it. I can't play with them anymore." She added that he only wanted to work with Michael Stipe of R.E.M.

"In the last few weeks, I was talking to Kurt a lot," Stipe said in a statement. "We had a musical project in the works, but nothing was recorded."

On March 18, a domestic dispute escalated into a near disaster. After police officers arrived at the scene, summoned by Love, she told them that her husband had locked himself in a room with a .38-caliber revolver and said he was going to kill himself. The officers confiscated that gun as well as a bottle of "assorted," unidentified pills that the singer had on him. Love told the officers where Cobain had stashed a Beretta .380 handgun, a Taurus .38 handgun, a Colt semiautomatic rifle, and 25 boxes of ammunition, all of which were confiscated. Though, later that night, Cobain told officers that he hadn't actually been planning to take his own life, the police report nonetheless described the incident as a "volatile situation with the threat of suicide." No one was arrested, and Cobain "left the residence" afterward.

Four days later, Cobain and Love took a taxi from their home in Seattle's Madrona neighborhood to the American Dream used-car lot near downtown Seattle. The taxi driver, Leon Hasson, says the couple fought the whole ride there. Still arguing, Cobain and Love entered the lot. According to lot owner Joe Kenney, Love was upset because, two days after they had purchased a Lexus on January 2, Cobain had returned it. Love wanted the car, but Cobain wanted something less ostentatious. Kenney adds that Love appeared unstable, and dropped several pills while walking toward a bathroom.

By this time, Cobain's family members, band mates and management company, had begun talking to a number of intervention counselors about treating Cobain's increasing heroin and psychological problems. One of these specialists was Steven Chatoff, executive director of Anacapa by the Sea, a behavioral health center for the treatment of addictions and psychological disorders, in Port Hueneme, Calif. "They called me to see what could be done," says Chatoff. "He was using, up in Seattle. He was in full denial. It was very chaotic. And they were in fear for his life. It was a crisis."

Chatoff began interviewing friends, family members and business associates in preparation for enacting a full-scale intervention. According to Chatoff, someone then tipped off Cobain, and the procedure had to be canceled. Nirvana's management, Gold Mountain, claims that it found another intervention counselor and told Chatoff a small lie to turn down his services politely.

Meanwhile, Roddy Bottum, an old friend of Love and Cobain's and the keyboardist for Faith No More, flew from San Francisco to Seattle to care for Cobain. "I really loved Kurt," Bottum says, "and we got along really well. I was there to be with him as a friend."

Nirvana guitarist Krist Novoselic staged his own separate intervention with Cobain, but the most grueling confrontation took place on March 25. That afternoon,, roughly 10 friends, including band mates Novoselic and Pat Smear, Nirvana manager John Silva, longtime friend Dylan Carlson, Love, Goldberg, and Janet Billig, manager of Love's band Hole (Bottum had already gone home) gathered at Cobain's home on Seattle's Lake Washington Boulevard to take a different approach with a new intervention counselor. As part of the intervention, Love threatened to leave Cobain, and Smear and Novoselic said they would break up the band if Cobain didn't check into rehab. At first, Cobain was unwilling to admit he had a drug problem, and did not believe that his recent behavior had been self-destructive. However, by the end of the tense five-hour session, Cobain's resolve had weakened and he agreed to enter a detox program in Los Angeles later that day. He then retired to the basement with Smear, where they rehearsed some new material.

Cobain and Novoselic.

However, once at the Seattle airport, Cobain changed his mind and refused to board the flight. Love had hoped to coax Cobain into flying to Los Angeles with her so that the couple could check into rehab together. Instead, she wound up on a plane with Billig. (The couple's daughter, Frances Bean, and a nanny followed the next day.) Love would say that she regretted leaving Cobain alone ("That '80s tough-love bullshit, it doesn't work," she said in a taped message during a memorial vigil for Cobain two weeks later). After a stop in San Francisco, Billig and Love flew to Los Angeles, and on the morning of the 26th, Love checked into a $500-a-night suite in the Peninsula Hotel, in Beverly Hills, and began an outpatient program to detox from drugs (Gold Mountain says it was tranquilizers).

Back in Seattle that evening, Cobain stopped by a woman friend and drug dealer's house in the upscale, bohemian Capitol Hill district. "Where are my friends when I need them?" she told a Seattle newspaper Cobain said to her. "Why are my friends against me?"

Capitol Hill neighborhood on the northeastern edge of downtown Seattle.

Cobain stayed in Seattle five more days before agreeing to go to Los Angeles for treatment on March 30th. Before leaving, he stopped by Dylan Carlson's condominium in the Lake City area of Seattle to ask for a gun because, Carlson says Cobain told him, there were trespassers on his Madrona property.

"He seemed normal, we'd been talking," Carlson, who was the best man at Cobain and Love's wedding, says. "Plus, I'd loaned him guns before." Though there is no registration or waiting period for shotguns in Seattle, Carlson believes Cobain didn't want to buy the shotgun himself because he was afraid the police would confiscate it, since they had taken his other firearms after the domestic dispute that had occurred 12 days earlier.

Cobain and Carlson headed to Stan's Gun Shop nearby and purchased a six-pound Remington Model 11 20-gauge shotgun and a box of ammunition for roughly $300, which Cobain gave Carlson in cash.

Cobain’s gun receipt from Stan’s Gun Shop, March 30, 1994.

"He was going out to L.A.," Carlson says. "It seemed kind of weird that he was buying the shotgun before he was leaving. So I offered to hold on to it until he got back." Cobain, however, insisted on keeping the shotgun himself. The police believe that Cobain brought the weapon home and stashed it in a closet. Novoselic reportedly drove Cobain to the airport. Smear and a Gold Mountain employee met Cobain in Los Angeles and drove him to the Exodus Recovery Center, in the Daniel Freeman Marina Hospital, in Marina del Rey, Calif. Cobain had spent four miserable days detoxing at Exodus in 1992, but left the center before his treatment was completed.

Despite his inability to proceed with his plan, Chatoff says he spoke with Cobain by phone several times before Cobain left for Los Angeles. "I was not supportive of that at all," says Chatoff of Cobain's admittance to Exodus, "because that was just another detox 'buff and shine.'"

Cobain spent two days at the 20-bed clinic. He talked to several psychologists there, none of whom considered him suicidal. Though Frances Bean and her nanny visited him, Love never did. On April 1 Cobain called Love, who was still at the Peninsula. "He said, 'Courtney, no matter what happens, I want you to know that you made a really good record,'" she later told a Seattle newspaper. "I said, 'Well, what do you mean?' And he said, 'Just remember, no matter what, I love you.'" (Hole were due to release their second album, Live Through This, 11 days later.) That was the last time Love spoke to her husband.

According an artist known as Joe Mama, a longtime friend of the couple's who was the last to visit Cobain at Exodus, "I was ready to see him look like shit and depressed. He looked so fucking great." An hour later, Cobain, in Love's words, "jumped the fence." Actually, it was a six-foot-plus brick wall surrounding the center's patio.

Though Exodus is a low-security clinic, and Cobain could have walked out the door if he had wanted to, he had something else in mind. One of Cobain's visitors remembers, "When I went to visit him, Gibby Haynes [of the Butthole Surfers] was in there with him. I don't know Gibby, but he's a nute. He was jabbering a mile a minute about people who had jumped over the wall there, stuff like 'Bob Forest went over the wall five times.' Kurt probably thought it would be funny."

Gibby Haynes and Cobain.

At 7:25 p.m., Cobain told the clinic staff he was stepping out onto the patio for a smoke and scaled the wall. "We watch our patients really well," says a spokesperson for Exodus. "But some do get out." Most of Cobain's friends and business associates who were in L.A. were at a concert by another Gold Mountain client, the Breeders, oblivious to the fact that he had escaped.

"After Kurt left, I was on the phone with Courtney all the time," says Mama. "She was really freaked out, so we drove around looking for him at all the places he might have gone. She was really scared from the beginning. I guess she could tell."

But Cobain was already on his way back to Seattle. He returned home on a Delta flight five and a half hours after his escape. By the time Love cancelled his Seafirst bank credit card and hired private investigator Tom Grant to track him down the following day, it was too late. In fact, according to police, cancelling the credit card made it even more difficult to find Cobain because Seafirst only records the type of business and amount of money for attempted charges on cancelled cards, not the precise location of the business. Love also reportedly hired a second private investigator to watch Cobain's drug dealer's home, a woman Love is said to have been jealous of to begin with.

When Cobain returned to his Madrona home, he found his former nanny, Michael DeWitt (whose nickname is Cali), staying there. "I talked to Cali, who said he had seen [Kurt] on Saturday [April 2]," says Carlson, adding that DeWitt described Cobain as looking ill and acting weird, "but I couldn't get ahold of him myself."

Neither could anybody else. The police believe Cobain wandered around town with no clear agenda in his final days. A taxi supervisor reports that Cobain was driven to a gun shop to buy shotgun shells (a receipt for the ammo was later found at Cobain's house). Neighbors say they spotted Cobain in a park near his house during this period, looking ill and wearing an incongruously thick jacket. Cobain reportedly spent time with some junkie friends, shooting up so much that they kicked him out because they were worried that he'd OD on them. Cobain is also believed to have spent time at his second home, in Carnation, Wash, where a sleeping bag was found. Next to it was a picture of the sun drawn in black ink above the words "cheer up," and an ashtray filled with cigarettes--one brand was Cobain's, the other wasn't.

On Sunday, April 3, someone (possibly Cobain) attempted to make several charges to his credit card. The amounts, ranging from $1,100 to $5,000, were apparent attempts to get cash. The following day, two more charge attempts were made, this time to get $86.60 worth of flowers. It was this same day that Cobain's mother, Wendy O'Connor, filed a missing-person's report. She told police that Cobain might be suicidal and suggested that they look for him at a particular three-story brick building, described as a location for narcotics, in Capitol Hill.

L to R: Cobain’s mother Wendy O’Connor, newborn Frances Bean, Cobain, and half-sister Breanne O’Connor.

Sometime on or before the afternoon of April 5, Cobain barricaded himself in the greenhouse above his garage by propping a stool against its French doors. The evidence at the scene suggests that he removed his hunter's cap--which he wore when he didn't want people to recognize him--and dug into the cigar box that contained his drug stash. He completed a one-page note in red ink. The top of the note was written in small handwriting, and never directly referred to suicide, leading some to believe it had been written ahead of time. The second half of the note was in much larger writing, and made direct reference to suicide (police handwriting experts have determined that both halves were written entirely by Cobain). Writing to Love, daughter Frances Bean, friends and fans, Cobain spoke of the great empty hole he felt had opened inside him. He also expressed his hope that Frances Bean's life would not turn out like his own.

Cobain’s suicide note.

"I haven't felt the excitement of listening to as well as creating music, along with really writing something for too many years now," Cobain scrawled, adding that "when we're backstage and the lights go out and the manic roar of the crowd goes out, it doesn't affect me the way in which it did for Freddie Mercury. . . . I've tried everything that's in my power to appreciate it, and I do, God, believe me, I do. But it's not enough. I appreciate the fact that I and we have affected and entertained a lot of people. I must be one of those narcissists who only appreciate things when they're alone. I'm too sensitive. I need to be slightly numbed in order to regain the enthusiasm I had as a child. On our last three tours I've had a much better appreciation of all the people I've known personally and as fans of our music. . . . I love and feel for people too much, I guess. Thank you all from the pit of my burning, nauseous stomach for your letters and concern during the last years. I'm too much of an erratic, moody person, and I don't have the passion anymore, so remember it's better to burn out than to fade away."

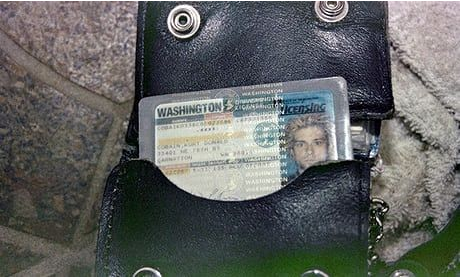

Cobain tossed his wallet on the floor, open to his Washington driver's license, which friends believe was to help the police identify him. Love reconstructed the rest of the tragedy for MTV: Cobain drew a chair up to the window, sat down, took some more drugs (most likely heroin), pressed the barrel of the 20-gauge shotgun to his head and--evidently using his thumb--pulled the trigger.

Though the county medical examiner has determined that Cobain died on the afternoon of April 5, someone tried to charge a $1517.56 cash advance on his credit card the following morning. The attempt was either made over the phone, or in person without the card. The police also report that two people say that Cobain's Capitol Hill heroin dealer told them Cobain had come by her apartment the night of April 5. The dealer denies the incident.

In a cruel twist of fate, it wasn't until April 6 that Love's private investigator, Tom Grant, arrived in Seattle. I was working with [Grant]," Carlson says, "and the day we were going to Carnation to look for him, we found out he was dead."

Carlson and Grant, a former deputy sheriff, also checked Cobain's Madrona home twice, but failed to search the greenhouse where Cobain's body lay. DeWitt left the main house and flew to Los Angeles on the afternoon of April 7, still unaware of the body nearby. Police say they never entered the house before Cobain's body was found, satisfying themselves with asking workers outside his house if they had seen Cobain.

Elsewhere on April 7, an emergency phone call was placed to 911 about a possible overdose victim at the Peninsula Hotel in Los Angeles. The police, the fire department and ambulances arrived at the scene, where they found Love and Hole guitarist Eric Erlandson. (Frances Bean and her nanny were staying in the room next door.) Love was taken to Century City Hospital, arriving around 9:30 a.m. She was released two and a half hours later. Lt. Joe Lombardi of the Beverly Hills Police says that Love was arrested immediately after her discharge and "booked for possession of a controlled substance, possession of drug paraphernalia, possession of a hypodermic syringe and possession/receiving stolen property."

Criminal lawyer Barry Tarlow, Love's attorney, says that contrary to published reports, Love "wasn't under the influence of heroin" and "didn't overdose." He says that "she had an allergic reaction' to the tranquilizer Xanax. Tarlow says the stolen property was a prescription pad that "her doctor . . . left there when he was visiting. . . . There were no prescriptions written on it." And the controlled substance? "It was not narcotics," says Tarlow. "It's Hindu good-luck ashes, which she received from her entertainment lawyer Rosemary Carroll.

Love was released at about 3 p.m. after posting $10,000 bail. (All charges against Love were later dropped.) She immediately checked herself into the Exodus Recovery Center, the same rehabilitation facility from which her husband had escaped a week earlier. The following day, April 8, she checked out when she received word that her husband had been found.

The first time Cobain's troubles made tabloid headlines was in August 1992, after an infamous Vanity Fair article was published in which its writer, Lynn Hirschberg, reported that Love had used heroin while pregnant with Frances Bean. (Love has denied this.) As a result of subsequent media attention, the Cobains were not allowed to be alone with their newborn daughter for one month.

After a long and taxing battle with children's services in Los Angeles, where they were then living, the couple regained custody of the girl. In a September 1992 Los Angeles Times article, Cobain admitted to "dabbling" in heroin and detoxing twice in the past year--a strategic move, according to an insider, to mollify children's services. In subsequent interviews, Cobain never admitted to using heroin after he and Love had detoxed before Frances Bean was born.

In the spring of 1993, after the band had recorded In Utero with producer Steve Albini in Minnesota, another frightening series of events began to unfold. First came good news: On March 23, 1993, following a Family Court ruling in Los Angeles, children's services stopped its supervision of the Cobains' child-rearing. But just six weeks later, on May 2, Cobain came home (then in Seattle's Sand Point area) shaking, flushed and dazed. Love called 911. According to a police report, Cobain had taken a large dose of heroin. As Cobain's mother and sister stood by, Love injected her husband with buprenorphine, an illegal drug that can be used to awaken someone after a heroin overdose. She also gave Cobain a Valium, three Benadryls and four Tylenol tablets with codeine, which caused him to vomit. Love told the police this kind of thing had happened before.

A month later, on June 4, the police arrived at the Cobains' home again after being summoned by Love. The two had been fighting over Cobain's drug use, a source says Cobain later told him. However, Love told the police that she and Cobain had been arguing over guns in the house.

Cobain was booked for domestic assault (he spent three hours in jail), and three guns found at the house were confiscated. One of those weapons, a Taurus .380, had been loaned to Cobain by Carlson. (Cobain picked up the guns a few months later; they were again confiscated in the March 1994 domestic dispute.)

Seven weeks later, on the morning of July 23, Love heard a thud in the bathroom of the New York hotel where the couple was staying. She opened the door and found Cobain unconscious. He had overdosed again. Nevertheless, Nirvana performed that night at the Roseland Ballroom. Fans never knew the difference.

A few days later, Cobain returned to Seattle. One friend says: "He just kept to himself. Every time he came back after a tour, he would get more and more reclusive. The only people that saw him a lot were Courtney, Cali and Jackie [Farry, a former babysitter and assistant manager]."

Though, according to Gold Mountain, Cobain's clinical depression had been diagnosed as early as high school, according to Gold Mountain, the singer never seemed to fully believe he had a problem. "Over the last few years of his life," says Goldberg, "Kurt saw innumerable doctors and therapists."

Many who were close to Cobain remember that the musician frequently suffered dramatic mood swings. "Kurt could just be very outgoing and funny and charming," says Butch Vig, who produced Nevermind, "and a half-hour later he would just go sit in the corner and be totally moody and uncommunicative." "He was a walking time bomb, and nobody could do anything about it," says Goldberg.

Butch Vig, producer of Nirvana’s album Nevermind.

On Sept. 14, In Utero was released. Even though Cobain had vowed not to "go on any more long tours" unless he could keep his chronic stomach pain from acting up, he detoxed from heroin, according to sources, and hit the road for a long stretch of U.S. Nirvana dates.

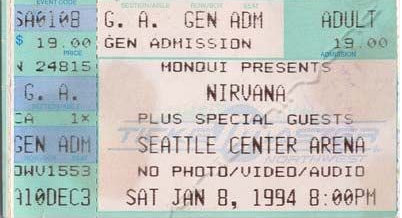

On Jan. 8, 1994, Nirvana performed what would be their last American show, at the Seattle Center Arena. The band then spent the next couple of weeks relaxing in Seattle. During that time, in a move considered uncharacteristic by many, Cobain authorized Geffen to make a few changes to In Utero. In order to get chains such as Kmart and Wal-Mart to carry the album, which the stores had previously rejected, Geffen decided to remove Cobain's collage of model fetuses from the back cover.

Nirvana’s final show in the United States.

Geffen also changed the song title "Rape Me" to "Waif Me," a name that Cobain picked, according to Ray Farrell of Geffen's sales department. "At first, Kurt wanted to call it 'Sexually Assault Me,'" Farrell says, "but it took up too much room. In the end he decided on 'Waif Me' because waif, like rape, is not gender specific. Waif represents somebody who is at the mercy of other people." The altered version was also shipped to Singapore--the only country where In Utero was banned.

Nirvana (minus Pat Smear, who was still at home in Los Angeles) emerged from hibernation on the weekend of Jan. 28 and spent three days in the studio. On Feb. 2, the band members left for Europe. They stopped in France to appear on a TV show and began their tour in Lisbon, Portugal, on Feb. 5. It was the first time Nirvana had scheduled so many consecutive dates in Europe. The band and crew traveled by bus. Cobain and Smear traveled in one bus; Grohl and Novoselic rode in another. According to road manager Alex Macleod, two buses were a matter of luxury, not animosity.

L to R: Dave Grohl, Krist Novoselic, Cobain, and Pat Smear.

"The shows went really well," recalls Macleod. "But Kurt was tired; I mean, we were traveling a lot."

About 10 to 12 days into the tour, heading back through France, Cobain began to lose his voice. For a while, a throat spray purchased in Paris and administered before shows helped ease his discomfort.

Cobain in Rome, Italy.

While Nirvana was in Paris--a week before Cobain's 27th birthday--photographer Youri Lenquette witnessed a chilling scene. Cobain showed up for a photo shoot for the French magazine Globe and struck up different poses with a sports pistol he had recently purchased. On one occasion, Cobain foreshadowed his own suicide by pressing the gun against his temple, pretending to squeeze the trigger, and miming the impact of the gunshot to his head. (Lenquette has decided not to release the photos.)

After a swing through a handful of French and Italian cities--including Rome--Nirvana performed in Ljubjana, in the former Yugoslavia, on Feb. 27 and, two days later, at Terminal Einz, in Munich, Germany. It would be Nirvana's final show. Cobain lost his voice halfway through the performance and, says Macleod, went to see an ear, nose and throat specialist the next day. "[Cobain] was told to take two to four weeks' rest," Macleod says. "He was given spray and [medicine] for his lungs because he was diagnosed as having severe laryngitis and bronchitis"

According to Macleod, the doctor who prescribed the throat spray to Cobain told him: "'You shouldn't be singing the way you're singing,' the same as they always say. "'You have to take at least two months off and learn to sing properly.' And he was like 'Fuck that.'"

The band postponed two more German shows--in Munich and Offenbach--until April 12 and 13 and took a rest. Novoselic flew back to Seattle the following day to oversee repair work on his house; Grohl stayed in Germany to participate in a video shoot for the film Backbeat (he played drums on the soundtrack); and Cobain and Smear headed for Rome. The band had made it through 15 shows with another 23 to go.

Cobain decided to stay in Europe. The plane trip and jet lag were too much to take in his condition. "He as much as anyone else was bummed out that they had to pull these two shows," says Macleod. "But there was no way that he could have gone on the next night."

On March 3, Cobain checked into Rome's five-star Excelsior Hotel. That same day, in a London hotel room, a writer for the British monthly Select was interviewing Love, who was preparing for an English tour with her band Hole. The writer says that during their talk, Love was popping Rohypnol, a tranquilizer manufactured by Roche, which also makes Valium. According to pharmacists, the drug is used to treat insomnia. It has also been used to treat severe anxiety and alcohol withdrawal and as an alternative to methadone during heroin withdrawal. (Gold Mountain denies withdrawal as an issue in Love's and Cobain's cases.) Known in some parts of Europe as Roipnol, the drug is not available in the United States. "Look, I know this is a controlled substance," Love said in the interview. "I got it from my doctor. It's like Valium.

According to Gold Mountain, Love, Frances Bean and Cali met Cobain in Rome the next afternoon. That evening, Cobain sent a bellboy out to fill a prescription for Rohypnol. In an uncharacteristic move, Cobain also ordered two bottles of champagne from room service. ("He never drank," his friends confirm.)

At 6:30 the following morning, Love found Cobain unconscious. "I reached for him, and he had blood coming out of his nose," she told Select in a later interview, adding, "I have seen him get really fucked up before, but I have never seen him almost eat it." At the time, the incident was portrayed as an accident. It has since been revealed that some 50 pills were found in Cobain's stomach. Rohypnol is sold in tinfoil packets; each pill must be unwrapped individually. A suicide note was found at the scene. Gold Mountain still denies that a suicide attempt was made. "A note was found," says a company spokesperson, "but Kurt insisted that it wasn't a suicide note. He just took all of his and Courtney's money and was going to run away and disappear."

Cobain was rushed to Rome's Umberto I Polyclinic Hospital for five hours of emergency treatment and then transferred to the American Hospital just outside the city. He awoke from his coma 20 hours later and immediately scribbled his first request on a note pad: "Get these fucking tubes out of my nose." Three days later, he was allowed to leave the hospital. Cobain's doctor, Osvaldo Galletta, says that the singer was suffering "no permanent damage" at the time.

Inside the ambulance with Courtney in Rome.

"He's not going to get away from me that easily," Love later said. "I'll follow him through hell."

The couple then returned to Seattle. "I saw [Kurt] the day he got back from Rome," says Carlson. "He was really upset about all the attention it got in the media." Carlson didn't notice anything abnormal about Cobain's health or behavior. Like many of Cobain's friends, he regrets that neither Cobain nor anyone close to Cobain told him that Rome had been a suicide attempt.

Sonic Youth guitarist and longtime Nirvana supporter Lee Ranaldo, who, like Nirvana, is managed by Gold Mountain, agrees. "Rome was only the latest installment of [those around Cobain] keeping a semblance of normalcy for the outside world," he says. "But I feel like I was good enough friends with Kurt that I could have called him up and said, 'Hey, how are you? Do you want to talk?'"

Lee Ranaldo of Sonic Youth.

"I never knew [Cobain] to be suicidal or anything like that," Mark Lanegan recalls. "I just knew that he was going through a really tough time."

The days after Cobain's death were filled with grief, confusion and finger pointing for all concerned. "Everyone who feels guilty, raise your hand," Love told MTV the morning after Cobain was found. She said she was wearing Cobain's jeans and socks and carrying a lock of her husband's blond hair. According to Gold Mountain, a doctor was summoned to stay with Love at all times.

"She's a strong enough person that she can take it," says Craig Montgomery, who was scheduled to manage a since-canceled spring tour for Hole.

"It was hard to imagine Kurt growing old and contented," adds Montgomery. "For years, I've had dreams about it ending like this. The thing that weirds me out is how alone and shut out he felt. It was him that shut out a lot of his friends.

Novoselic later said that he believed Cobain's death was the result of inexplicable internal forces: "Just blaming it on smack is stupid. . . . Smack was just a small part of his life."

"I think drugs tampered with his life," Faith No More's Bottum agrees, "but they weren't as huge a part of his life as people make it out to be."

The news of Cobain's death was first reported on Seattle's KXRX-FM. A co-worker of Gary Smith, the electrician who found Cobain's body, called the station with what he claimed was the "scoop of the century," adding, "you're going to owe me a lot of concert tickets for this one."

"Broadcasting this information was kind of an eerie decision to make," says Marty Reimer, the on-air personality who took the call. "We're not a news station." Cobain's sister, Kim, first heard of her brother's death through radio reports, as did his mother, Wendy O'Connor. "Now he's gone and joined that stupid club," O'Connor said to a reporter, referring to Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Brian Jones and Jim Morrison. "I told him not to join that stupid club."

After Reimer called the Associated Press with the story, MTV played reruns of Nirvana's Unplugged performance and Seattle DJs took to the airwaves. "He died a coward," barked one Seattle DJ on KIRO-FM, "and left a little girl without a father.

"I don't think any of us would be in this room tonight if it weren't for Kurt Cobain," Pearl Jam's Eddie Vedder told a capacity audience during a Washington, D.C., concert the night that Cobain's death was announced. Vedder left the crowd with the admonition: "Don't die. Swear to God."

Outside Cobain's Seattle house the afternoon after his body was found, 16-year-old Kimberly Wagner sat on a wall for four hours, crying and fielding queries from news-hungry TV stations and magazines. "I just came here to find an answer," she sobbed. "But I don't think I'm going to."

Nearby, Steve Adams, 15, stood with a friend. As a Gray Line tour bus full of curiosity seekers passed by, he explained what Cobain's music meant to him. "Sometimes I'll get depressed and get mad at my mom or my friends, and I'll go and listen to Kurt. And it puts me in a better mood. . . . I thought about killing myself a while ago, too, but then I thought about all the people that would be depressed about it."

The Seattle Crisis Clinic received roughly 300 calls that day, 100 more than usual. Dr. Christos Dagadakis, director of emergency psychiatry at Harborview Medical Center, says, however, that "there was no particular increase in overdoses or suicide attempts coming in to our emergency room.

The following evening, on April 10, Seattle mourned Cobain as some 5,000 fans gathered in the park near the Space Needle to commemorate him. Love read excerpts from Cobain's suicide note in a taped message to the crowd, interspersing her own emotional responses to the confessions and doubts of her "sad little sensitive underappreciative Pisces Jesus man." "I should have let him, we all should have let him have his numbness," she sobbed. "We should have let him have the thing that made him feel better."

Vigil in Seattle, April 10, 1994.

It wasn't until hours after this candlelight vigil that Seattle experienced its first possible Cobain-related suicide. After returning home from the vigil, Daniel Kaspar, 28, ended his life with a single bullet.

The effects of Cobain's suicide reverberated around the globe. In Australia, a teenager committed suicide in an apparent tribute to Cobain. In southern Turkey, a 16-year-old fan of Cobain's locked herself in her room, cranked Nirvana music and shot herself in the head. Friends said she had been depressed ever since hearing about Cobain's death.

Elsewhere, on the evening of the vigil, Cobain's family scheduled a private memorial service at the Seattle Unity Church a few blocks away from the Seattle Center. There was no casket; Cobain's body was still in the custody of the medical examiners (he was later cremated). The Rev. Stephen Towles began the service by telling some 150 invited guests: "A suicide is no different than having our finger in a vise. The pain becomes so great that you can't bear it any longer."

Novoselic delivered a short eulogy afterward. "We remember Kurt for what he was: caring generous, and sweet," he said. "Let's keep the music with us. We'll always have it forever."

Carlson read verses from a Buddhist poet. Love, clad in black, read passages from the Book of Job and some of Cobain's favorite poems from Arthur Rimbaud's Illuminations. She told anecdotes about Cobain's childhood and read from his suicide note. She included parts that she had not read on tape for the vigil. "I have a daughter who reminds me too much of myself," Cobain had written.

Gary Gersh, who signed Nirvana when he was with Geffen (he is now president of Capitol Records), read a faxed eulogy from Michael Stipe. Last to speak was Danny Goldberg. "I believe he would have left this world several years ago," Goldberg said, "if he hadn't met Courtney."

When the service ended, Love headed to the Seattle Center nearby, where the vigil had just ended. Fans were burning flannel shirts, shouting for Nirvana music (which they got) and taunting the police, who were trying unsuccessfully to keep them out of the public fountain. Love mingled almost unnoticed in the sea of mourners, clutching her husband's suicide note in her hand. She disappeared and then reappeared with an armload of Cobain's old clothes and possessions, which she distributed to his fans. She described herself to bystanders as "angry" and emotionally "messed up."

Kim Warnick of the local group Fastbacks surveyed the scene with KNDD-FM music director Marco Collins, who had helped organize the mass memorial. "He would have loved this," she told him.

"All these kids," Collins replied, as he surveyed the undernourished teens with dyed hair, troubled eyes and torn jeans milling around him, "they look like they came from his world."

As of this writing, neither Grohl nor Novoselic has told his story to the press, though, along with Cobain's family and Gold Mountain, they will be setting up a scholarship fund for Aberdeen, Wash., high-school students with "artistic promise regardless of academic performance."

Children's services departments in both Seattle and Los Angeles confirmed that they had no caseworkers assigned to Frances Bean. Though Cobain did have a will, it was unsigned and therefore invalid at the time of his death. With no will, Love and Frances Bean have become the only heirs to his estate (which includes assets of over $1.2 million and debts of less than $740,000). Love, meanwhile, donated all of Cobain's guns, including the one he used to kill himself, to Mothers Against Violence in America.

Kurt Cobain Memorial Park, Aberdeen, Washington.

Love spent time holed up in Seattle for a while before flying to New York, where she went on a lingerie shopping spree. After Love returned to Seattle, another tragedy unfolded around her. Kristen Pfaff, the bassist in her band, Hole, was preparing to move from Seattle to Minneapolis on the evening of June 15 when she locked herself in her bathroom around 9:30 p.m. The following morning, Paul Erickson, the bassist in the Minneapolis band Hammerhead, who had spent the night at the house, found her slumped over the side of the tub, kneeling in five inches of water. Police say they found "syringes and what appeared to be narcotic paraphernalia" in a purse on the bathroom floor, but were unable to determine the cause of her death.

"It was an accident," Hole drummer Patty Schemel told a Seattle newspaper afterward. "She loved life and this shouldn't have happened."

Courtney Love communicated her grief on online, where she had been engaging in an active discourse with fans, friends, and enemies for several weeks. "Pray for [Kurt] and Kristen," she wrote. "They hear it i know . . . . My friend has been robbed of her stellar life my baby has no dad . . . . Thank you for respecting the finest man who ever lived, that he loved a scum like me is testament enough to his empathy."

Suicide is not the answer. If you are ever considering harming yourself, remember, there is hope:

In the United States, contact the Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255, or go to their website https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org

You can also contact the Crisis Text Line at 741741 or visiting https://www.crisistextline.org.

International suicide prevention resources: http://suicideprevention.wikia.com/wiki/International_Suicide_Prevention_Directory