Some interesting facts I found in a book about the occult and Rock and Roll.

The following is excerpted from Season Of the Witch: How the Occult Saved Rock and Roll by Peter Bebergal, published by Tarcher.

Terry Manning was hunched awkwardly over the master vinyl disk of the album that would be called Led Zeppelin III, his hand preternaturally steady as he engraved the words on the runoff—the smooth inner ring where no grooves had been cut. A special platter was placed on top of the disk that exposed only the area he was working in, so he was prevented from accidently scratching the vinyl and ruining the master. Guitarist Jimmy Page, excited and stoned, looked on. It was Page who’d implored Manning to carve the message that would end up on every copy in every record store and in the hands of every fan. Unless you looked for it, the words would essentially be invisible, but their very existence on the record would impress a great truth that Page was convinced the world needed: “Do what thou wilt.” This single moment serves as microcosm of the entirety of the influence occult would have on rock and roll. It would spread out into rock’s atmosphere in ways neither Manning nor the band could have predicted. The timing was perfect. Music fans were anxiously waiting for the next incarnation of Dionysus to remind them the god was not dead. He was merely biding his time while the astral trails of psychedelic rock dissolved. Led Zeppelin perfectly encapsulates the power of the occult imagination, how it continues to see expression, and how it was able to completely propel rock and roll into electrifying new directions.

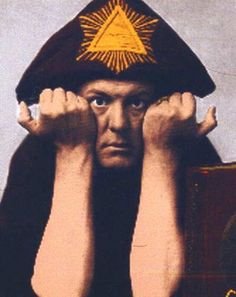

Manning, an old friend of Page and a veteran of the still fairly young rock industry, had been called in to engineer the record. On a humid July day in 1970 at the Mastercraft studio in Memphis, he and Page did the final mix and then the master. It was going to be a slightly different album, Zeppelin’s hard- rock edge softened with British folk influences. But the opener, “Immigrant Song,” was pure Zeppelin, a Viking-inspired revelry about cold Nordic winds and the halls of Valhalla. At the time Page was obsessed with Aleister Crowley, whose notorious turn-of-the-century magical and sexual escapades were idealized by much of the sixties counterculture as brilliant feats of radicalism. Page believed Crowley was a “misunderstood genius” and thought he had a duty to spread Crowley’s prime directive: “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law.” While Page’s own passion could be infectious, it was not always easy to know when he was just looking to stir things up. Manning later said he never knew of Zeppelin’s guitarist ever actually trying to cast a spell or perform a ritual. But Page had invested a huge sum on rare Crowley manuscripts, and even went so far as to buy Crowley’s home on the shore of Loch Ness—a mansion rumored to be haunted by the spirits the dark magician had conjured. By agreeing to inscribe the Crowley line on the master pressing of the album, Manning decided to humor his friend even though the risk of damaging the master was great.

Twenty years later—almost to the day, as he remembers it—Manning was flipping channels when he came across a televangelist preaching on the devil’s influence on rock and roll. He held up a vinyl copy of Led Zeppelin III, an album by then considered one the greatest rock records of all time by critics and fans. As the camera zoomed in on the album, the televangelist’s fingers began to trace the words engraved on the runoff. The TV preacher explained that these were the words of one of the most devilish men who ever lived, the black magician and Satanist Aleister Crowley. Manning sat back, smiled. He said to himself, “I did that.”

…

Today, Page tends to dismiss his interest in Crowley as just one of many novel curiosities he’s explored in his life. In a 2012 interview with Rolling Stone, he even seemed a bit annoyed to have to keep answering questions about it all these years later: “What attracted me to [the Pre-Raphaelite poet and painter] Dante Gabriel Rossetti? You won’t be asking me questions on that. But you would ask me about Crowley. And everyone is going to prick up their ears and wait for great revelations. . . . It’s taken out of all proportion. There was a balance to it. I wouldn’t be here now if there hadn’t been.” But no matter the force of his protestations, in the accepted history of Led Zeppelin the story of Page’s magical dabblings is indispensable.

In Hammer of the Gods, one of the earliest and most popular biographies of the band, author Stephen Davis quotes a much younger Page saying something a bit less “balanced”: “Magic is very important if people can go through it. . . . I think Aleister Crowley’s completely relevant today. We are still seeking for truth—the search goes on.” No source is provided for the quote, but it certainly echoes the thoughts of a typical young man in the early 1970s for whom taboo and dark things held a special appeal. Let’s chalk it up to his age and the context of his life a rock star. In a 1976 Rolling Stone interview, he talked candidly about his interest in Crowley, but was wary of coming across as proselytizing. He notes Pete Townsend’s name-checking of the Indian spiritual leader Meher Baba in the title of the song “Baba O’Riley” as something he never wanted to do with Crowley. But he was not shy in proclaiming that he incorporated Crowley’s ideas into his “day-to-day life.” Here Page is more mature, less gushing, likely feeling he no longer has to convince anyone of anything. His 2012 interview, where he almost seems exasperated with the question, is just as indicative of a long life where one’s ideas have mellowed.

Page’s willingness to discuss his fascination with Crowley and magick ebbed and flowed. But over many years of interviewing Page, Guitar World editor Brad Tolinski was able to gain confidence with the reticent guitarist, and in their conversations a clearer picture emerged. With Tolinski, Page admits that his esoteric inquisitiveness was not limited to Crowley, but took in the whole spectrum of “Eastern and Western traditions of magick and tantra.” But the media found Crowley an easy mark for referencing a sinister figure par excellence, and he made for more interesting interview questions than, say, an obscure grimoire. Nevertheless, Crowley did represent for Page the very best example of “personal liberation.” As a young man with unlimited money and access to drugs, Page took it literally: “By the time we hit New York in 1973 for the filming of The Song Remains the Same, I didn’t sleep for five days!”

But the cultural truth is much more important than even how Page talks about the occult at different stages in his life. Culture is where the story of the occult and rock is created, not in coy interviews with musicians. Along the trajectory of a band’s life, the facts are akin to mythology, a grand narrative that as is as much about how the myth gets transmitted as it is about the how the myth gets made. But for Led Zeppelin, their mystique was grounded in something intentional, something that was as much a part of what they conceived and gave birth to as it was the frenzied media and fan speculation. Page tells Tolinski, “I was living it. That’s all there is to it. It was my life—that fusion of music and magick.”

Page first encountered the writings of Aleister Crowley when he was eleven years old, and while intrigued, he couldn’t really penetrate Crowley’s often impenetrable and assertive prose. When he returned to the magician’s writings as an adult he was taken by Crowley’s philosophy of self-liberation. In the late 1960s, Page began collecting rare Crowley works and in 1970 purchased the home once owned by the magician known as the Boleskine House on the southeastern shore of Loch Ness in Scotland, a place that would continue to attract legends of mystery and monsters. Crowley purchased the house in 1899 as it was, according to the magician, situated in a place that was particularly conducive to magical experiments. Crowley was at the time attempting a ritual by which a magician meets his or her Holy Guardian Angel, a year-long operation that requires chastity, intense prayer, and the conjuration of spirits both good and evil.

The ritual is found in a medieval grimoire known as the Sacred Book of Abramelin the Mage, a text filled with complex and decidedly religious invocations (“In the name of the blessed and holy Trinity . . . “), list after list of infernal and heavenly names (“Akanef. Omages. Agrax. Sagares . . . “), and byzantine rules (“Take of myrrh in tears, one part; of fine cinnamon, two parts; of galangal . . . “). Nevertheless, the practical purpose of the grimoire is disappointingly prosaic: becoming invisible, discovering treasure, and even locating a misplaced book. Crowley believed, however, the Holy Guardian Angel was not in fact an external divine presence, but a stand-in for the “higher self.” He never completed the ritual at the Boleskine House. But the attempt was enough to charge the grounds with a current of ominous radiance.

Prior to Crowley, the house was already considered a place of ill repute. A church once situated there is said to have burned down, killing all the people inside. Crowley’s reputation for black magic made the place twice haunted. It’s uncertain what Page actually did there except hold lavish parties. The guitarist eventually sold the house and opened a bookstore in London called Equinox, named after Crowley’s book series (an attempt at a literary journal for the occult set). Page worked hard, and spent a lot of money, to keep the store from looking like a typical musty bookstore or a head shop, an establishment just then beginning to line store shelves with quartz crystals. Page, ever the romantic dandy, had an architect design the shop in the style of a nineteenth-century occult lodge replete with Egyptian motifs and Art Deco trappings.

Page’s burgeoning curiosity with Crowley coincided nicely with Robert Plant’s own love of Celtic folklore and fantasy, particularly by way of J.R.R. Tolkien. References to Tolkien’s hobbit-populated Middle Earth in Led Zeppelin’s lyrics were fairly explicit, with Plant name-dropping Tolkien’s delightfully grim locations, such as Mordor and Misty Mountains, as well as the nefarious Gollum and dark riders called Ringwraiths. Plant also wanted his lyrics to hold mythological meaning and he once described Celtic mysticism as the vital source for the spirit of Led Zeppelin. “[Those are] the lyrics I’m proud of,” he told a reporter for New Musical Express in 1973. “Somebody pushed my pen for me, I think.”

Plant grew up in West Bromwich, England, an area of England rich with folklore and legends. Pre-Christian mythology was at his doorstep. And Page’s magick guitar work was the perfect vehicle to hitch folk fantasy lyrics. “Immigrant Song” offers a powerful example. The song is a dragon’s fiery breath unsealing the new decade of the 1970s, a period that would fuse mythology, fantasy, and the occult in exactly the same way the band would with their music. Lester Bangs, the frenetic genius of rock criticism, prophesized this union of imagined worlds carved out of ancient myths and the spiritual rebellion at the heart of rock and roll in his review of Led Zeppelin III for Rolling Stone in 1970.

Bangs makes special note of Page’s opening cry with its “infernal light of a savage fertility rite.” Even more so in “Immigrant Song,” Bangs identifies the future of rock: “You could play it, as I did, while watching a pagan priestess performing the ritual dance of Ka before the flaming sacrificial altar in Fire Maidens of Outer Space with the TV sound turned off. And believe me, the Zep made my blood throb to those jungle rhythms even more frenziedly.” Led Zeppelin rapidly became the touchstone for all the weird and occult permutations of the 1970s. From Tolkien to Crowley, from pulp fantasy to pop-magick, the darker edge of the 1970s occult leanings was found everywhere.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

http://realitysandwich.com/229927/led-zeppelins-dance-with-the-occult/