Richard III, a historical tragedy and one of the earliest works by the one and only William Shakespeare displays a protagonist who is solely bent on evil. While other Shakespeare villains, like Edmund in King Lear or Macbeth, have a good nature too, Richard appears to be a thorough-going villain incapable of redemption.

From his very first soliloquy in Act 1.1, Richard seems immune to his own conscience and is “determinèd to prove a villain” (1.1.30). His sudden attack of conscience in Act 5.4 seems out of place, as he has had no previous second thoughts about murdering people, even his own relatives. The brief awakening of Richard’s conscience is not brought about by the belief of his guilt, but by fear. Since this fear and self-reflection is short-lived, Richard’s soliloquy in 5.4 should not induce an audience to feel sympathy for him.

Although Richard’s terrifying dream should force Richard to reflect on his crimes, he instead focuses on his fear, rather than his guilt. Instead of repenting of his deeds, Richard instead blames his conscience saying, “O coward conscience, how dost thou afflict me!” (5.4.157). Richard calls his conscience a coward, as if it is cowardly to feel remorse for committing murder. Richard’s conscience does not speak on its own, but through the voices of the dead: “My conscience hath a thousand several tongues, / And every tongue brings in a several tale, / And every tale condemns me for a villain” (5.4.172–74). These tongues that condemn him to “despair and die” are the voices of the ghosts of young Prince Edward, Henry the Sixth, Clarence, Rivers, Grey, Vaughan, the two young Princes, Hastings, Lady Anne, and Buckingham (5.4.106,14,19, 28,35). The terror of hearing his doom pronounced to him by the dead does not cause him to see his guilt and need of repentance and only causes him to fear the future battle with Richmond. Richards asks Ratcliffe: “What think’st thou, will our friends prove all true? … O Ratcliffe, I fear, I fear” (5.4.192–93). Richard is controlled by his fear and thus fails to recognize or accept his guilty conscience, which only results in pathetic self-pity.

Richard’s fear only brings on self-pity rather than true remorse in response to his dream. Richard admits that he is “a villain” and he has committed “hateful deeds,” but the next second he declares, “Yet I lie; I am not” (5.4.169–170). When plotting the murder of the young princes, Richard admits that “[t]ear-falling pity dwells not in this eye” (4.2.65). Richard has no pity for his live victims, and even after being accused by their ghosts, he still has no compassion for them. Instead he turns to pathetic self-pity, saying: “I shall despair. There is no creature loves me, / And if I die, no soul will pity me. / And wherefore should they, since that I myself / Find in myself no pity to myself” (5.4.179–82). Richard’s whole soliloquy oozes of self-pity, as he repeats the words “me,” “my” and “myself” over and over again and remarks that “Richard loves Richard” and no one else (5.4.162). Richard’s focus is always on how he can further his own interests and his self-pity should leave no sympathy for him.

Richard’s fearful and despairing soliloquy may tempt an audience to be sympathetic to him, but he deserves no one’s sympathy because it is clear that he is still the unrepentant tyrant. Richard quickly recovers from his attack of conscience as he says, “Let not our babbling dreams affright our souls. / Conscience is but a word that cowards use, / Devised at first to keep the strong in awe. / Our strong arms be our conscience, swords our law” (5.5.37–40). Richard dismisses his dream and his conscience as cowardly, thus banishing any guilt he might feel from his mind. Even after his terrifying nightmare, Richard shows his arrogance when he is still willing to commit murder. When he learns that Stanley is no longer serving him, he interrupts the Messenger to declare, “Off with his son George’s head!” (5.5.73). Richard has obviously learned nothing from his dream and has no regrets for murder. Because of his lack of a change of heart after the soliloquy in Act 5.4, no audience should sympathize with Richard. He is a black hearted tyrant through and through and he deserves to be killed and dethroned.

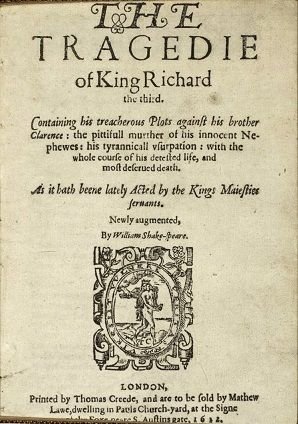

Shakespeare, William. The Tragedy of Richard III. Edited by John Jowett, Oxford UP, 2000.

I think characters that are without a redeeming quality, but with a lot of evil ambition, can be really fascinating and Shakespeare was so well at crafting characters that intrigued the audience.

So true! Ian McKellen does a fantastic job playing Richard in the 1995 film production. Although the film makers do not directly say it, Richard resembles Hitler and the world around him resembles the Nazis regime. If you haven't seen it, I would highly recommend it!