Ursula Le Guin’s use of Taoism should shape one’s interpretation of The Lathe of Heaven in its entirety. While the Western world might be tempted to view the novel from Haber’s point of view and see progress and change as a good thing, readers are meant to be sympathetic to George’s claim that change is dangerous. The Tao is represented by George, who embodies the yin/yang, while Dr. Haber, who believes he can play God, is “destroyed on the lathe of heaven” (26). Taoism is most clearly represented in The Lathe of Heaven through George’s beliefs and personality and is contrasted by Dr. Haber’s flawed optimistic portrayal of change, progress, and the possibility of a man-made utopia.

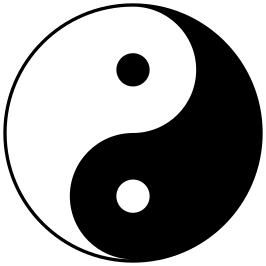

While Taoist philosophy is evident in the epigraphs at the beginning of each chapter, George Orr not only seems to have a Taoist outlook on the world, but also embodies it in his personality. Dr. Haber sneeringly comments on this saying, “You’re of a peculiarly passive outlook for a man brought up in the Judeo-Christian-Rationalist West. A sort of natural Buddhist. Have you ever studied the Eastern mysticisms, George?” (82). George appears passive because he believes that “it’s wrong to force the pattern of things” and prefers to let events occur in their own way and time rather than controlling them with his dreams (82). George’s personality also portrays this belief. George is referred to by Heather as “Mr. Either Orr” (90). Later, Dr. Haber says the same thing when he tells George the results of the tests he had him undergo: “you’re a median. […] If you put them all onto the same graph you sit smack in the middle at 50. […] Both, neither. Either, or. Where there’s an opposed pair, a polarity, you’re in the middle; where there’s a scale, you’re the balance point” (137). George embodies the yin/yang as he becomes a duality; he is both passive and strong at the same time. Heather sees George as “the strongest person she had ever known, because he could not be moved away from the center” (96). In this way, George becomes the jellyfish in the opening paragraphs of the novel that allows itself to “drift,” “tugged from anywhere to anywhere” (1). The jellyfish image gives “a feeling of carefreeness, or perhaps a suspension of anxiety” as the jellyfish readily surrenders itself to the will of the ocean (Selinger 76). George, as the jellyfish, allows himself to be borne on the ocean, while Haber, who is represented by the violent and obtrusive image of the land, “disrupts the oceanic unity” (Selinger 76). As a representative of the Tao, George becomes an image of balance and unity, while Haber’s obsession with progress and change disrupts unity and brings instability and destruction.

While George believes that the world should be balanced and unified, Haber likes change and progress and sincerely believes that he can bring a utopia to the world. Haber believes that “[t]he more things go on moving, interrelating, conflicting, changing, the less balance there is—and the more life” (139). For Haber, balance is stifling and restrictive while change is life-giving. Haber sees nothing wrong with taking matters into his own hands, playing God, and changing things in the world, for what he sees as for the better. He accuses George of not wanting to change the world for the better, saying: “You are afraid of losing your balance” (139). Haber brags to George of all the improvements he has made to the world: “Eliminated overpopulation; restored the quality of urban life and ecological balance of the planet. Eliminated cancer as a major killer. […] Eliminated the color problem, racial hatred. Eliminated war. Eliminated the risk of species deterioration and the fostering of deleterious gene stocks” and he is in the “process of eliminating—poverty, economic inequality, the class war, all over the world” (147). Haber believes he is changing the world for the better and takes pride in the fact that with his changes “this world will be like heaven, and men will be like gods!” to which George eerily replies, “We are, we are already” (150). George recognizes that “it’s not right to play God with masses of people” (155). Haber’s hunger for power ultimately destroys him as he does not understand the dangers of playing God and creates a nightmare and goes insane. The epigraph for chapter 3 summarizes Haber’s experience: “To let understanding stop at what cannot be understood is a high attainment. Those who cannot do it will be destroyed on the lathe of heaven” (26). Haber refuses to keep George’s brain a mystery and insists on obtaining the power to dream effectively for himself, thus denying the Tao. Heather remarks that “there is a whole of which one is a part, and that in being a part one is whole; such a person has no desire whatever, at any time, to play God. Only those who have denied their being yearn to play at it” (108). Haber denies his being and attempts to play God and make a utopia and is ultimately destroyed by his own ambition.

As characters, George and Haber represent the Taoist and Western philosophies as George believes that life should be balanced while Haber insists that progress and change is a good thing. The Tao asserts that “[l]ife is made possible by not knowing. The demand for certainty blinds one to life’s plenitude” (Galbreath 43). Le Guin’s Taoist leanings emerge in The Lathe of Heaven as the characters must learn that the mysterious is best left untouched. Anyone, like Haber, who attempts to pursue understanding what “cannot be understood […] will be destroyed” (26). As scholar Frederic Jameson clearly puts it: “the effort to ‘reform’ and to ameliorate, to transform society in a liberal or revolutionary way is seen […] as a dangerous expression of individual hubris and a destructive tampering with the rhythms of ‘nature’” (156). Reform denies the will of the Tao, which seeks balance with the universe. Change leads to destruction while balance ultimately leads to happiness.

Western culture believes that science is the vehicle that can propel society into a utopia and that progress is a desirable thing that will bring about success and happiness. In stark contrast, the Tao believes that a person should remain in balance with the universe and not attempt to assert power to change anything. Readers in a Western society must embrace Taoist philosophy in order to comprehend the conclusion of Le Guin’s novel The Lathe of Heaven, where Haber is destroyed by his own utopic ambitions and George refuses to tamper with the new universe.

Galbreath, Robert. “Holism, Openness, and the Other: Le Guin’s Use of the Occult.” Science Fiction Studies, vol. 7, no. 1, 1980, pp. 36–48. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4239309.

Jameson, Fredric. “Progress versus Utopia; Or, Can We Imagine the Future?” Science Fiction Studies, vol. 9, no. 2, 1982, pp. 147–158. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4239476.

Le Guin, Ursula. The Lathe of Heaven. Scribner, 1971.

Selinger, Bernard. Le Guin and Identity in Contemporary Fiction. UMI Research Press, 1988.

*Pictures show various editions of the cover design for Le Guin's acclaimed novel.