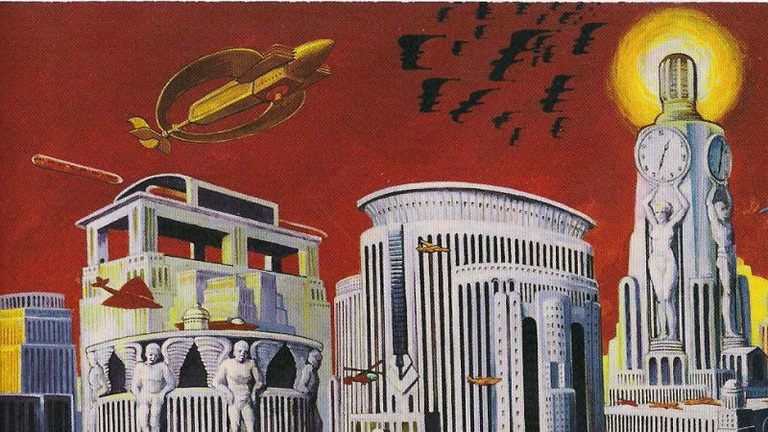

In his article “The Death of Utopia Reconsidered,” Leszek Kolakowski describes social utopia as trying to accomplish “perfect and everlasting human fraternity” and equality (237,40). However, utopias can only result in anti-utopias because attempts to achieve “[s]ocial perfection has irreversibly killed human personality” (239). Utopias try to “abolish tension and suffering” in society but this only reduces people to anti-humans because tension and suffering is an essential part of life (241–42). Kolakowski concludes his article by saying, “[t]he victory of utopian dreams would lead us to a totalitarian nightmare,” which is exactly what Russian author Yevgeny Zamyatin describes in his 1924 dystopic novel We (247). Although society seems utopic to We’s protagonist, D-503, he is really living in a dystopia where “fraternity” and “equality” have only reduced the people to ciphers and machines.

In We, the One State and the Benefactor create a controlled society where ciphers can be happy in perfect equality with their brothers and sisters. However, a happy society means that there can be no freedom, and thus no individuality. D-503 describes an “ancient legend about paradise,” where Adam and Eve are given the choice of “happiness without freedom or freedom without happiness” (55). D-503 has been programmed to be believe that the ability to choose is an evil from which the One State guards the ciphers, since happiness can only be achieved in non-freedom. As a result, no freedom creates perfect equality where “‘WE’ is divine, and ‘I’ is satanic” (113). Individuality must be eradicated in order for a utopic “WE” to exist. When D-503 finds himself isolated and alone, he describes himself as “a human finger, cut off from the whole, from the hand. …And the strangest, most unnatural thing of all is that the finger doesn’t want to be on the hand, with the others, at all. It wants to be alone” (92). D-503 finds this desire “to be alone” incredibly unsettling and as unnatural as a severed finger is unnaturally unattached to the rest of the body. D-503 has been told all his life that he happiest when he has no freedom, and when he begins to find opportunities to choose, he recognizes that he is rebelling against blissful equality.

This supposed blissful equality is achieved by the One State, which has reduced its people to ciphers who have become little more than machines. The ciphers are called by their impersonal “names,” like “D-503,” “S,” “O,” “R-13” and “I-330.” These non-personal, numeric titles destroy individuality and make everyone an equal in society. This leveling is also accomplished by the non-existent private life in society. The ciphers live in transparent glass boxes where everyone can see what everyone else is doing at all times. The only time the blinds can be closed is when two ciphers are given permission from the Table to have intercourse. The One State attempts to conquer Love by proclaiming that “‘[e]ach cipher has the right to any other cipher as sexual product’” (21). Individuals are reduced to products, labelled by numbers and letters that can be summoned for sexual gratification. Even the ciphers’ mail must “pass through the Bureau of Guardians” where other people read everything before they receive it (45). When people are reduced to impersonal products, individuality is destroyed and only tyrannical equality remains.

When D-503 and other ciphers begin to rebel against the One State, the Benefactor radically responds by surgically altering people to become literal machines. D-503 catches a glimpse of what it means to be human when he begins to “[develop] a soul” (79). However, the One State responds to this by sending people to the Great Operation where the Imagination, the part that makes a person a human, is permanently removed. Ciphers, which are already less than human, are transformed into “person-looking tractors” (166). They literally become “machine-equal” as their imagination is extracted and they become perfectly submissive to the One State and the Benefactor (158). The chilling conclusion to We shows how equality and perfect fraternity does not create a utopic society, but rather a freedom-less, machine-like nightmare where individual humans are numbers, products, and ultimately expendable.

Kolakowski, Leszek. “The Death of Utopia Reconsidered.” The Tanner Lectures on Human Values, edited by Sterling M. McMurrin, Cambridge UP, 2011, pp. 229–47.

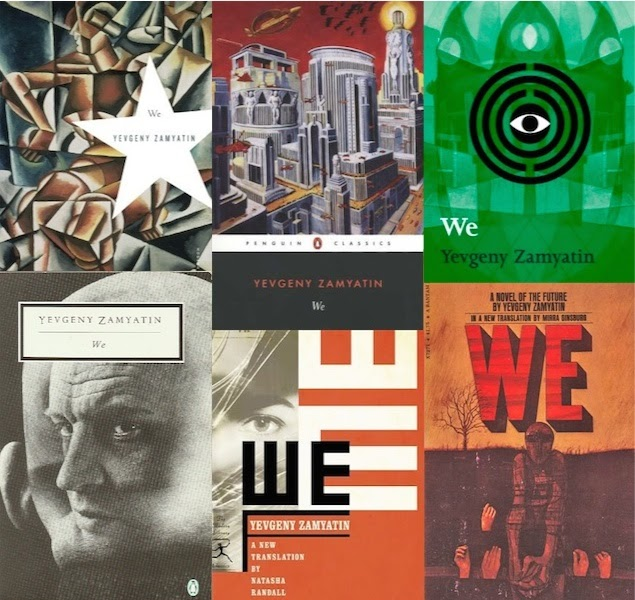

Zamyatin, Yevgeny. We. Translated by Natasha S. Randall, Modern Library, 2006.

*Photos of various book cover editions

This really sounds like an interesting book. It's not that we don't have enough dystopias, but this one was written during full-blown revolution and yet managed to see through it it seems.

I find it particularly fascinating that Zamyatin was imprisoned for writing We, which was banned from being within the Soviet Union. He eventually was allowed to emigrate to Paris. We was considered a dangerous book, which is understandable because of its bold critique of both socialism and communism.

Hi @rennoelle You wrote the best. I love these Let's come forward. Hope to get a better post. I would also be more delighted if you subscribe to my posts too.

wrote very good for the readers .