As we have been learning about and discussing non-profit health, one topic that has repeatedly popped up (thanks in part to @jfeagan) is non-profit death. What happens when a non-profit can no longer sustain itself, especially in a capitalist environment that prioritizes growth over all other measures of success?

A large portion of non-profits insist on staying in operations, even if that means losing their audience or reputation, burning out staff, or creating even more of a financial burden. When the most responsible and sensical answer is to downsize or close the organization, few non-profits are willing to take that path.

So what happens when one does?

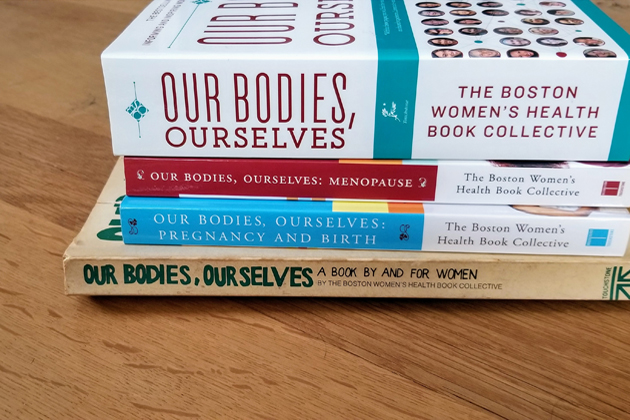

Image courtesy of Our Bodies, Ourselves

What was the Boston Women's Health Book Collective?

In 1970, a group of 12 women in the Boston area published a pamphlet titled "Women and Their Bodies." A combination of personal stories and careful research, this pamphlet explored a number of topics pertinent to women's health at a time when women were encouraged to depend solely on male doctors for health-related information. The pamphlet was soon expanded into a book titled Our Bodies, Ourselves (hereafter "OBOS"). With an acknowledgment that women's health issues involve social, economic, and political factors, and a frank inclusion of contemporary issues like abortion, the book spurred an international health movement.

But 9 editions, 4 million copies, and almost 50 years later, the Collective (which had since renamed itself to OBOS) had an announcement.

"A Message About the Future of Our Bodies Ourselves"

On Monday, board chair Bonnie Shepard announced that after a staff retreat several months ago, OBOS would be transitioning to a volunteer-run organization. This decision was based on several factors, including financial woes, a changed publishing industry, and the plethora of available resources regarding women's health. The announcement also outlined changes in leadership, an end to updating and physically publishing OBOS, and a transfer of various initiatives to relevant feminist organizations.

How did the public react?

Interestingly, in the wake of the announcement, the comments section turned into an unofficial memorial/oral history collection, as people shared their memories and gratitude for OBOS. Commenters wrote stories about the different ways they've kept their tattered first editions still bound, how they followed OBOS's instructions for viewing their cervix with hand mirrors, and even one person wrote about how they named their two cats Simon and Schuster, in honor of OBOS's original publisher. (No, really.)

Aside from these personal accounts, comments showed mixed reactions that tended to fall into two camps:

- Some commenters thanked OBOS for all they had done, acknowledging how difficult of a decision this must have been.

- Other commenters were (understandably) more upset, arguing that in the current administration, which has fueled wars on both AFAB bodies and on science, OBOS is needed more than ever.

Overall, every single comment (that I read, at least) expresses a deep gratitude for OBOS -- a great amount of public trust. In contrast with other institutions, such as the Berkshire Museum that sold donated Norman Rockwell paintings to ensure its own survival, OBOS places the greatest emphasis on its audience. Granted, OBOS is a different kind of organization -- it has no historical collection, and thus there is nothing to deaccession. However, OBOS still does not prioritize its publication as its primary mission and asset. The organization prioritizes its public, which in OBOS's case, means maintaining access to current editions of the book, support of relevant organizations, and ongoing lobbying on behalf of women's health.

While there are plenty of parts of the transition plan that have yet to be announced, the board's open communication has made it clear that OBOS's main asset is its audience.

Sources

Jewish Women's Archive, "New York Times reviews Our Bodies, Ourselves." https://jwa.org/thisweek/mar/13/1973/our-bodies-ourselves

Bonnie Shepard, "A Message about the Future of Our Bodies Ourselves," Our Bodies Ourselves, Apr 2, 2018. https://www.ourbodiesourselves.org/2018/04/a-message-about-the-future-of-our-bodies-ourselves

Nina Simon, “Instead of Selling Objects, Build Public Trust,” Museum 2.0, Jan 8, 2018. http://museumtwo.blogspot.com/2018/01/instead-of-selling-objects-build-public.html

Stefanie Weiss, "Our Bodies, Ourselves taught women about sexuality and reproductive health," The Washington Post, Oct 3, 2011. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/our-bodies-ourselves-taught-women-about-sexuality-and-reproductive-health/2011/09/22/gIQAdkV6IL_story.html?utm_term=.65064d47d0bf

100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History Initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment conducted by graduate courses at Temple University's Center for Public History and MLA Program, is exploring history and empowering education. Click here to learn more.

I think you finally found an example of a nonprofit that has closed/downsized itself without being perceived as a failure. They can say, we were so successful in meeting our mission that we're no longer needed--and that allows them to claim success in the midst of downsizing. Can we apply this to failing history nonprofits? I imagine most of them don't have missions that they can claim they have successfully completed, especially if their missions involve preserving a collection.

Good point, is a history nonprofit mission ever accomplished?

That's an interesting question, and I would say no. That's definitely the case for OBOS, their mission is to disseminate information on and advocate for women's health, which unfortunately is still an ongoing mission.

I'd say instead that the approaches that nonprofits (history or otherwise) take to fulfilling their mission needs to change, as society changes. In OBOS's situation, their mission was primarily fulfilled through print publications, and they realized that today, people are more often getting their information from non-print resources, and when their own digital campaign failed, they realized their approach to their mission was no longer effective. Instead of trying to keep afloat a structure that was no longer working, they acknowledged other organizations doing the same work but better, and are in the process of adjusting their model so they can better support those organizations.

All of this is to say, it's not an issue of whether a history nonprofit can completely accomplish/complete their mission, it's an issue of how nonprofits are approaching their mission, which nonprofits are doing that more effectively than others, and which nonprofits are the most equipped to change with the times.

I sure hope some archivists are collecting the public responses to this move! Sounds like a great case study.

I am a little skeptical about the organization continuing as a volunteer organization. We've seen a lot of examples of bad mergers but it seems to me like OBOS' assets would make a really good addition to a lot of more healthy organizations, right?