This week, my classmates and I are reimagining how funds can operate within the cultural sector. We'll be discussing the different sources from which museums and other historical institutions generate revenue, how that money is managed, and how that revenue can best reflect needed expenditures.

This is a timely conversation to have, since at the beginning of this year, the Metropolitan Museum of Art announced it will be changing its admissions policy. The institution, which has been "the only major museum in the world that relies exclusively on a pure pay-as-you-wish system or that does not receive the majority of its funding from the government" will only continue that pay-as-you-wish structure for New York residents -- visitors from out of state will pay flat rates, such as a $25 ticket for adults.

External facade of the Met. Image courtesy of sailko on Wikimedia Commons

Who pays for the arts?

There was an immediate uproar. Some questioned the logistics of the arrangement -- Will visitors be carded? How will this affect undocumented immigrants? Others questioned the ethics of the situation -- All museums should be free! How can you charge when you just installed a multi-billion dollar fountain at the entrance?

Questions of the latter kind indicate a public misunderstanding of how museums acquire and use funds. They also indicate the necessity of a larger conversation we must have as a society: Who pays for the arts? Is it the responsibility of individual visitors, private donors, or the government?

In an American context, we have been having this conversation since the founding of our country. In the 1790s, Charles Willson Peale founded his Peale Museum, considered to be the first publicly accessible museum in the United States. By the early 1800s, Peale needed funds beyond admission to operate the museum, and he appealed to Congress for supplementary funding. Despite the museum's overwhelming popularity, including among the country's leaders, Thomas Jefferson replied that Congress could not agree whether institutions not named in the Constitution could be funded. Soon after Peale's death in 1827, it closed.

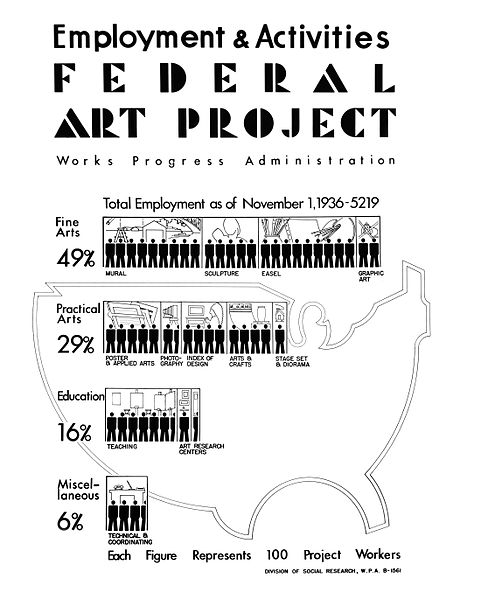

This debate is still happening. While there have been occasional exceptions -- like the Federal Art Project, a federal program to create jobs as part of the New Deal -- the government has repeatedly indicated that it is not interested in funding museums to the degree needed. While the NEA and NEH often fund large projects hosted or organized by museums, the current administration has considered cutting those programs altogether during past budget talks.

Poster advertising the Federal Art Project. Public domain image

courtesy of the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Who wants to pay to keep the lights on?

Many museums turn to private donors for a large portion of their fundraising, such as through annual appeals. However, these donors often are not interested in funding operating costs, as opposed to new exhibits and programs. In a manual for direct mail fundraising, Kay Partney Lautman and Henry Goldstein state that donors may acknowledge operating costs like the electrical bill, but discussing those needs will not pique donors' generosity. Direct mail fundraising letters should instead name an enticing cause that demands immediate action. Not only does this preference lead to earmarked funds that can only be used for the project rather than operating costs, but it also encourages unhealthy financial attitudes that prize growth over stability.

This prioritization partially applies to grants as well, which often center around specific projects. While grant applications can ask for money for broader causes, such as part of the salaries of staff involved in the given project, or could apply to behind-the-scenes projects like facility maintenance, basic operating costs like the electric bill are often still not covered.

During conversations about the Met's updated policy, many people brought up the idea of corporate sponsorship of museums. Large corporations with millions of dollars in profit would easily be able to pay for non-profit organizations' operating costs, and they would likely be interested in the publicity of having their name associated with cultural organizations. However, with the funding credits that would likely accompany this type of donation, would the public be comfortable going to, say, the Coca-Cola Philadelphia History Museum?

Visitors' burden

Of course, we can't expect visitors alone to carry a museum financially. In fact, admissions only accounts for 14% of the Met's total revenue. However, many supporters of free museums argue that admission costs further the exclusivity of the cultural sector. Cost creates a barrier to many potential visitors who cannot pay admission fees. These costs also support and further the museum world's history of systematic oppression such as white-centrism and colonialism, which can make people of color, immigrants, and other marginalized groups to feel unwelcome to begin with, even if they could pay.

So what's the answer here?

Of course, there is no easy answer to this conundrum. While I agree with many other public historians that museums should be free, this is often an unrealistic goal for many institutions, especially smaller and non-urban ones. Museums and other historical institutions must find their own particular balance between seeking federal funding, private donations, grants, and admissions fees, based on their audience and their mission. They must also develop the financial literacy to manage the funds they do have well. But as we move forward in this conversation, we should keep in mind that someone must bear this financial responsibility, and ask ourselves: What is ideal? What is realistic? And how can we compromise between those two answers?

Sources:

Hart, Sidney and David C. Ward. "The Waning of an Enlightenment Ideal: Charles Willson Peale's Philadelphia Museum, 1790-1820." Journal of the Early Republic 8 no. 4 (1988): 389-418.

Lautman, Kay Partney and Henry Goldstein. Dear Friend: Mastering the Art of Direct Mail Fund Raising. Washington, D.C.: Taft Corporation, 1984.

100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History Initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment conducted by graduate courses at Temple University's Center for Public History and MLA Program, is exploring history and empowering education. Click here to learn more.

Does anyone think Coca-Cola or any other big for-profit entity would want to align itself with a needy institution and thereby possibly damage its own brand?

Another thought: How about the entire field agree and put into practice an across-the-board rate, a percentage of all gifts and grants that would go toward indirect costs. If it was 25%, a donor of $100,000 for an exhibition would know upfront that $25,000 of the total would be allocated toward operations.

Maybe that hypothetical wasn't the best example... I like your idea about an automatic percentage of donations going to operations, but I wonder how that would affect the amounts people donate. Especially for donation packages built around the costs of specific projects or opportunities, would donors still want to give the same amount (and thus not fund the project to the desired degree) or would donors be willing to give extra to fulfill both the project's needs and operations allocation?

You raise some important questions at the end @charliehersh. I think you are correct in that museums and historical institutions must find their own particular balance in order to succeed. I think such a balance will be easier to find when there is more collaboration between and innovation from the relationship between the cultural and private sector. I am just not sure how it is possible to get the private sector more interested in the cultural sector. Whether or not the public is comfortable with the Coca-Cola Philadelphia History Museum might be less important than if Coca-Cola is comfortable or interested in such a museum.

I think that the private sector is becoming more interested in philanthropy in general. Maybe not in actually useful public service like using clean energy or reducing waste, but appearing to be considerate, like the Pepsi commercial with the protesters, or Budweiser's recent Superbowl commerical about their disaster relief. I don't think it will necessarily be difficult to make the jump from "helping" in this regard to the cultural sector, as long as it comes with enough opportunity for advertising. I know that NMAJH at least has recently started a Corporate Partnership program (though more with local businesses than large conglomerates), though I'm not sure how common that model is.

Neither of these are my field, but the situation reminds me of wildlife conservation. I wrote about that, here, a while ago. To the best of my knowledge, entrepreneurship is the only sustainable funding model that has been discovered for just about any purpose we can name. Free market environmentalists have a saying, "If it pays, it stays." One example of a self-funding conservation site is Hawk Mountain, not too far from Philadelphia.

So the question becomes: "How can museums raise revenue from their art while allowing visitors to view it for free?"

Even when the government pays for something, the value was ultimately created by someone who produced a product or service. So, if I ran the museum, I would not like to have the government play middle-man. Instead, I'd be thinking about premium products (raffles to meet the artists, art lessons, gift shops, etc...) and opt-in gameification. For example, something like a scavenger hunt in the museum. Visitors could pay a fee to join the game, and the first person to find the answer to a question about some obscure characteristic of a piece of art work in the museum wins a prize, with a new challenge each day (or hour, or whatever...)

And of course, there's Steemit. ; -)