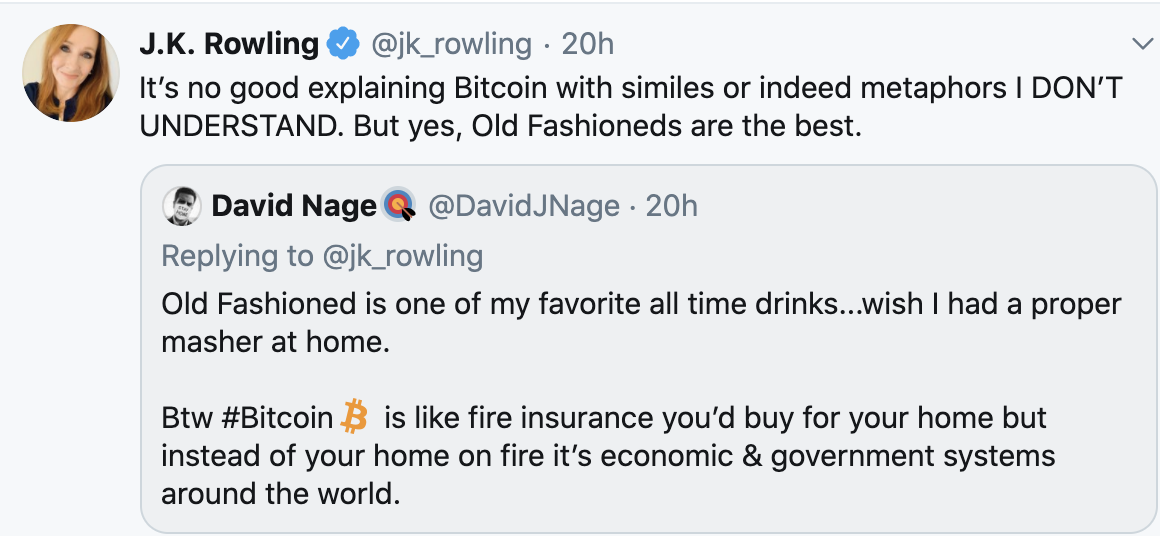

There has been somewhat of a twitter-war regarding J. K. Rowling and her understanding/ignorance of Bitcoin and cryptocurrencies/blockchain technology in general. She is in this case, whether she likes it or not, an exponent of the point of why I write this article.

Even the very rich, don't fundamentally understand money or the importance of having such an understanding, but it is extra ridiculous when they explicitly DON´T want to know, in the same vain as "why would I care about that" or "you people are weird with that nerdy interest in money".

Now, I am normally not triggered by anything famous people or politicians say. It is usually not of any particular importance. One thing that does bother me though is when influential persons are will-fully ignorant of something of such a monumental importance as money. It strikes a chord in my aversion against people who have everything you could possibly buy with money, while showing such ridiculous indifference to the thing that enables their lush life.

Most people on this planet are slaves to the money their state/central bank forces them to "work" for, through taxation. It is controlled by people who can enrich themselves by "printing" their own money in an elaborate shell game based on indebting the population (fractional reserve banking).

If you ask a number of individuals what money is, you are likely to get as many different definitions as the number of individuals you ask.

Why is this so? Why is the most important aspect (in my opinion) of "the economy", so poorly understood, that most people really do not have much of a clue about it, except that it is something they "get" for "working" and they use to "pay" for "stuff" with.

Understanding money is a deeply philosophical endeavour and it is in fact no wonder that most people have no clue how to define it. Most of those who have control over money, do not want most people to understand what it is, how it is made, who controls it and why it apparently have to be a monopoly controlled by the state and a central bank working in an untouchable alliance.

When you ask philosophers, mainstream economists and even "Austrian" economists, you usually get a list of "qualities" that money MUST have in order to be (considered) (good) "money".

The list goes something like this:

(Descriptions here are partly "mainstream" and partly mine)

Money must have:

1a. Recognisability

An individual should be able to recognise the money. In other words, its money attributes should be obvious to any individual.

1b. Durability

Its money attributes must not change over time (Ultimately indestructible)

1c. Divisibility

If you need to make a transaction with less of the money you have, you should be able to split it into any specific (smaller) parts, that still maintain the same money attributes. (Malleable and Homogeneous)

2a. Fungibility

Each identical quantity of the money, must be equally valid for a given (economic) transaction

2b. Portability

You must be able to transfer any specific quantity of the money to the place of an intended (economic) transaction

2c. Stability

The quantity of money you need, to perform any specific (economic) transaction, must not change over time

2d. Scarcity

There must not be too high a quantity of the money

Let me take the points on the list one by one.

Recognisability.

How do you recognise money? Well ... In order to recognise something it would be fair to say that it must exist. Without going too far into metaphysics and epistemology, the only way to recognise (or have knowledge of) some "thing", is to experience it. So how do individuals experience "things"? Via their senses. There are five of those: sight, hearing, smell, touch and taste. The register of each of these come in the form: colour, sound, aroma, feel and taste.

So when you "recognise" a thing, it must be a combination of one or more of these sense data. Which one of them do you use to identify money? What colour does it have? Is it a specific colour? No. Does it have a specific sound? No. Does it have a specific aroma, feel or taste? No. So in reality, it is impossible to "recognise" money, without a previously defined set of specified sense data. But who would decide what those should be? Would it just follow from culture, habits or such? And then a consensus arrived at - defining "this is the sense data of money"? No, I would say.

Durability

is dependent on time and you can only register aspects of the "effects" of time by letting time "go" sufficiently long to register that aspect. So can you observe durability as such? No, it takes time and if durability is something in the order of decades, it is very tedious to use that measurement to figure out if it is money.

Yes you can "trust" that other individuals has heard stories about a certain money's durability, but to be absolutely philosophically rigid, that is not knowledge, at least not your knowledge. Hear-say is not knowledge and as such you cannot know, except for the duration that you are not going to use the object you consider (your) money, if it is money.

Divisibility

is more straight forward. It seems. Check out if it is malleable, with tools that seems fit for the job. Can it be divided into separate, smaller parts and do they seem not to change in any way other in that they have a smaller quantity than that of its original whole? If yes, it seems that it is divisible. Now, an important point is that a lot of things are divisible, without being (considered) money, so the divisibility alone proves nothing, except that you cannot rule out that it could be money.

Fungibility.

Easy to test. Have two identical moneys in the same quantity at see if the same trade can occur with each of them. I don't see this as particularly relevant, if everything else is equal. It is another way of saying that if it is (good) money, identical quantities are equally acceptable as money in a transaction.

It seems to me that this list is somewhat of a conglomeration of various philosophical writings not taking overlaying aspects of various points on the list into account. It seems almost like redundancy. One could maybe say that fungibility connects quality and quantity - by stating that if the quality of the money is sufficient each equal quantity has the same transaction "power".

Portability.

If the only money available is a giant two ton stone, it could work as money, as there is no alternative. A curious example of this is the story of the stone money on the island Yap. They used huge carved out stone wheels, sometimes larger than a man, as money. The money rarely moved out of the place they were first created, yet they seemed to work well as money anyway for the Yap people. So it seems that portability is not exactly a necessary attribute for a money.

The question is rather that if better alternatives appear, they will probably, inevitably take over as a new money. If it is very portable, which means that a sufficient quantity of the money is containable, not very heavy and not too small and not too voluminous, it is less tedious to bring around for trading if the other part in the trade needs to hold it.

Stability

cannot be observed. It is usually understood as stable exchange value. This is a tricky one as it is not each unit of money that can have this attribute in itself. It is only the absolute quantity of the money that influence the stability of the individual units of it. If the absolute quantity is constant and the quantity of goods that can be traded is constant, then it is only changes in demand, that can generally change the quantity of money necessary for the occurrence of a specific transaction.

It would be preferable if the only use of any commodity used as money is that it is only used as money. If it has other uses, then to some extend this will influence its stability. As time goes by and equilibrium sets in, this may not be all that big of a deal. But a money that actually can NOT be used for anything else than money would possibly have the best stability, all else being equal.

There is actually no particular reason why something could not be money if it is very "unstable" (the absolute quantity changes fast). It can, but it is more advantageous for someone who wants to save money, that it becomes more scarce or at least stays the same. An increase in the absolute quantity (inflation) of the money only benefits those who introduced that new money. Inflation is one of those aspects of money that is hardest to understand. and this article will no go deeper into that, since it could probably fill another article of equal size. Safe to say that inflation must be defined as an increase in the overall quantity of money and the opposite, deflation a decrease in the overall quantity.

Prices a market regulated ration, over time, between the total amount of money and the average perceived values of each particular commodity times its quantity. So when everything else is equal and you inflate the quantity of money to the double, prices will regulate on the market to about the twice what it was before the inflation. Other aspects regulate prices, like change in supply, demand, fashion and more.

Those who are trying to save over time suffers a loss of transaction power after inflation, all else equal, as more money is now chasing the same amounts of goods, while the savers quantity stays the same.

Scarcity

cannot be observed. Scarcity is a relative term where a general quantity of a money used in transactions is compared to the general quantity of "stuff" received from the other part of a transaction. It is a relative term in that it indicates a money typically has a much smaller physical "footprint" than the stuff which it can buy in a transaction (a little money buys a lot of stuff). But on the other hand, it should not be too scarce, because then it would not be possible to divide it up in usable chunks for trade, if it is of a physical kind, since they would be infinitesimally small.

Scarcity is often confused with hardness. A hard money is one that cannot easily be increased in absolute quantity. Instead, scarcity and portability is somewhat of the same kind. The less "scarce" it is, the less relatively portable it is, obviously, if it is of a physical kind.

So what am I left with !?

Recognisability, durability, divisibility and to some extend fungibility is about describing "qualities". But when you look closely at the descriptions and definitions, you are actually not describing anything sensory about anything.

Recognisability exposes this most clearly. None of the five senses are used to "recognise" money.

Durability is not instantly observable. It is based on tradition or a lifetime of experience.

Divisibility is a comparison of two or more partitions of a larger quantity and is not as such a quality you can observe. Each part must be divisible in perpetuity, otherwise it would not be considered good money. But who would do that !

Fungibility is redundant as it is dependent on other qualities being the case first and then it just follows.

Portability is a weird term in the digital age as it clearly is derived from the idea of precious metals historically has been the most popular form of money. What it really means is that the "easier" it is to transfer it to a trade, the better money it is. Lots of things are portable, but not necessarily useful as money

Stability. Yes it should preferably be able to buy the same amount of stuff I did yesterday or last year, or a decade or more ago. But I cannot detect the stability of the money by observing it. I have to wait and see if it is stable. And if it is not, well then it is too late.

Scarcity I cannot detect this either. It could be unique this thing I hold or it could be vastly common throughout the universe. I have no way of knowing by observing it.

So when it all comes down - to me at least - it is a bit of a disappointing endeavour to try and use these traditional ways of figuring out if something is money and how good a money it is if I manage to figure out if it is money.

I want to take a new approach. Well - it is new to me.

If we take a lump of gold or a piece of paper, it is clear that the thing itself is observable, but the problem is there is no way of observing whether or not it is money.

Money is not a thing you can observe. This must be the conclusion so far. And yet, if it is not a thing it does not exist except in somebody's mind and that is not a good and stable "kind" of money. people forget, people manipulate etc. The need for money arises when one side in a trade cannot deliver what the other side wants at that time and place. The part who cannot get the commodity he/she wants, because the other side does not have it, still may want the trade to occur and then delay the acquisition of the wanted commodity until later. When a trade can occur where both parties in a trade gets the commodity they want is usually called "coincidence of wants".

Then the only way to do this is, for the one who cannot get the wanted commodity to accept something else instead which can later be exchanged in another trade for that most wanted commodity. In principle, any "thing" would do. A cow, a twig, a lump of gold, a flute etc. But imagine yourself in that situation. What would be your concern about receiving something else that you later needed to "trade" to get the most wanted commodity?

My main concern would be to choose the "thing" that I was most sure somebody else, particularly the one who traded my wanted commodity at some other time and place. Which one would that be? That is not clear ... it depends on the other side in the trade, the time and the place. There is no guarantee, even if everyone else considers something money, that any particular person will accept that "commodity" in a trade.

In prisons, cigarettes have been know to be used as money. Why? First of all because pieces of "official" money probably is unavailable and even it was available it would not be of the same use as outside the prison. And if you sit there alone with your money, and no one wants to trade or have something you want to buy, you just sit there. At least cigarettes can be smoked.

In this prison scenario, cigarettes becomes money, not because there is something intrinsic about that specific commodity or because of the time and place as such but because:

MONEY IS THE SUBSTITUTE COMMODITY, MOST PEOPLE WILL ACCEPT, INSTEAD OF THEIR WANTED COMMODITY, WHEN THERE IS NO COINCIDENCE OF WANTS IN AN EXCHANGE

or in other words:

MONEY IS THE MOST LIQUID COMMODITY, AT A SPECIFIC TIME AND PLACE

(Liquid means the commodity that (you believe) most people will accept as a substitute for another commodity in an exchange)

Excellent post, been interested in different ways of exchange for a long time and that included lot of similar thoughts so far. Hive is one example of community-created value.

Understanding money is not easy, the fish does not think about the water, it just swims. It is taken for granted, but the problem goes deeper, than most can imagine.

My long-time hobby has been travelling around, visiting banks and ask the employees and higher-ups, what money is and how it is created. 1 person out of hundreds knew the answer.

Have attended conferences with economists, zero knowledge or pure misinformation. When the so-called experts have no clue, how the commonfolk would be much better off?

Thank you :-) I agree with you. It is the combination of the human min and specific commodities, the truth lies, but since most people consider the commodities in themselves the sole description, they will inevitably fail in establishing a definition of money :-)