We call it an epidemic today, but for centuries medical experts encouraged the use of heroin.

When Heroin Was “God’s Own Medicine”

By Annie Garau on December 8, 2017

We call it an epidemic today, but for centuries medical experts encouraged the use of heroin.

History Of Heroin

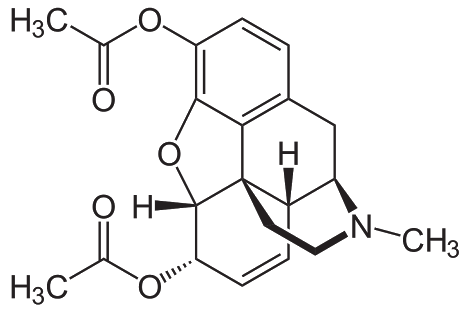

Wikimedia Commons

Medicinal heroin bottle, circa 1920s.

Opium — the yellow/brown dried poppy juice used to make morphine and heroin — has been numbing pain and claiming addicts longer than any other drug known to man.

Though today they’re mostly associated with the deadly epidemic quickly spreading across America, opiates — specifically heroin — didn’t always have such a bad rap. In fact — and as far back as ancient times — doctors would prescribe them for, well, just about everything.

It’s even suspected by some that the Egyptian illustrations documenting the death of King Tut — images of a pharaoh flailing about in strange ways — actually depicted the king on an opium high.

Starting in the 1500s, after a Swiss-German doctor visited the East and brought the poppy back with him, the substance became popular in Western medicine, with the apparent mantra being “Take this for anything that hurts.”

Indeed, once manufactured into morphine and heroin, which are identical except for the dosage (heroin is three times stronger), medical experts found that opiates helped with sleeping problems, digestion, diarrhea, alcoholism, gynecological issues, and babies’ teething pain, just to name a few.

Experts held opiates in such high esteem that William Osler, one of the physicians who founded Johns Hopkins Hospital, is even said to have referred to heroin as “God’s own medicine.”

While people typically took heroin for more hardcore diseases like bronchitis, individuals popped other forms of the drug the same way one might with Tums and Advil today.

A “Quiet Addiction” And The History Of Heroin

By the middle of the 19th century, Harper’s magazine reported that 300,000 pounds of opium were shipped to America each year, with 90 percent of it used recreationally.

And with Alexander Wood’s 1853 invention of the hypodermic syringe, America’s opium addiction reached new catastrophic heights — and a stigma developed surrounding its users. As Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote, “A frightful endemic demoralization betrays itself in the frequency with which the haggard features and drooping shoulders of the opium drunkards are met with in the street.”

Elite circles thought of heroin users as poor and low-class, with Harper’s reporting that “beggar-women” fed opiates to their babies.

In reality, though, most of the addicts in the 19th century were middle- and upper-class women – since they were the ones at home with easy access to the medicine cabinet. Indeed, surveys at the time noted that 56 to 71 percent of U.S. opium addicts were middle- to upper-class white women who purchased the drug legally.

As drug experts Humberto Fernandez and Theresa Libby write of the 19th century epidemic:

“It was a quiet addiction, almost invisible, because the women stayed at home. This was due in part to male dominance in the social sphere and the perception that it was not right for a decent woman to frequent bars or saloons, let alone an opium den.”

Still, a handful of decades later, the addiction’s association with the urban poor had solidified. In 1916, the New Republic wrote of heroin users that “The majority [of users] are boys and young men who… seem to want something that promises to make life gayer and more enjoyable. It would almost seem that their desire for something to brighten life up is at the bottom of their trouble, and heroin is but a means.”

According to Fernandez and Libby, by the late 19th century, “God’s own medicine” collapsed into a full-blown epidemic, with a rate of addiction three times as high as the 1990s heroin crisis.

Even in the face of such a staggering problem, it took the U.S. government until 1925 to strongly regulate the substance it had finally recognized as a “major social problem.” In spite of government crackdowns, it took several decades more for social and medical circles to turn against the drug.

Still, the drug has retained its hold on many Americans. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, heroin use more than doubled among young adults ages 18–25 in the past decade.

Yet as the historical record shows, the heroin crisis is not new. It just isn’t “quiet” anymore..jpeg)

Hahaha