Some of you may have heard, some of you may not have heard.

The expedition is over. For me at least.

2 years of planning, 1 year of training mentally and physically, writing off most of my work-life balance. All done.

Please don’t “half-read” this email. I’m about to give you the raw truth, and nothing but the truth. I’m still in shock. Gathering my thoughts to write this has been difficult. So here goes.

I have just been released from hospital in Kathmandu after being diagnosed with HAPE, High Altitude Pulmonary Edema, and began to develop signs of HACE, High Altitude Cerebral Edema. I was evacuated in the middle of a full-scale Himalayan blizzard, it took 3 of us 6hrs to get down to a 4×4 that shot me back to KTM. The doctors here in KTM told me I was very lucky to have been rescued and had we left it another 24 hours I would have fallen unconscious and most likely it would have led to my demise.

If it weren’t for the advice from my good friend Ramsey Chamaa, and Gabriel Filippi for the advice they gave while things progressed, I would most likely not be here writing to you right now. Many thanks also to Dr Alain Baldo for further invaluable advice.

Thank you Elia Saikaly and Dawa Tenzing Sherpa for helping me get down to safety through the storm that enveloped the entire North West face of Cho Oyu.

For now… here is my tale.

CHO OYU – The Ogre.

So when I last left you, we were with our Chinese Liason Officers, the plan was to go from Cho Oyu basecamp up to a very odd place called “Mid-Camp”. Mid-Camp is a clearing at best. More like a really bad open air Beirut-car park. Unwelcoming, dirty, and uneven- only this car park is covered in Yak-poo.

Here you will find 5 or 6 tents, occupied by Tibetans that run small “tea houses”. They are very nomadic in nature, not a far cry from Bedouin tents in the Middle East. Big tents that you can stand in, almost marquee-like, about the size of a small living room. Relatively comfortable circumference of padded bench space, with a wood-burning heater as the pièce de résistance. Useless because all they burn is Yak-Shit here, sure it warms you up a little, but trust me, the fumes that ensue are not worth the warmth. A mismatch I think.

The owner, a charming elderly Tibetan lady greeted us kindly with piping hot milk tea, and a warm smile. Out of the tent door, an unrestricted view of the prize, up-close and personal, Mt Cho Oyu, peering down at us in all its magnificence.

That night we met two young Tibetan girls. 15 years old. Never been to school, only speak Tibetan and some Mandarin. We were shocked to hear that they are road-workers. Building roads in sub zero temperatures. So sad. Supporting their families by doing hard-labour. The kind of labour that a British builder would tell you to go f yourself at even the thought of it. Courageous.

As soon as we got there, Elia and I pulled our sleeping bags out and made ourselves comfortable, ate some very welcome packed tuna lunch that we prepared earlier in the day. We looked at each other, knowing the climb had just begun. Night fell, and with it began another sleepless night, short of breath. I could not breathe while lying down, so I literally sat up all night staring at the tent walls, feeling it all cave in and become one. Tomorrow’s going to be tough to Advanced Base Camp (ABC) if I don’t get any rest. It’s going to be double the effort in the ever-increasing altitude and ever-thinning air. Try and sleep. Just shut your eyes, and let sleep come to you. I gasp for breath. I can’t. I can’t breathe. I feel choked if I lie down. Sit up. Thaaaat’s better. I’ll get more rest by sitting up like this. At least I can breathe again. I watch the ghostly effect of my condensed breath dance in the shadow of my head torch. Another long night. Again. I think I snatch an hour’s sleep. Somehow.

It’s morning, and Elia is irritable. Not talkative. I give him space. He makes a call to his girlfriend on the sat phone. Its snowing outside, so he stays in the tent and looks funny with one arm holding the satellite device pointing out the tent, and him crouched down in the corner trying to chat to Amanda. It takes only a moment to pack after breakfast (porridge with some honey scored from the lovely tent-lady-mmmm) and we set off for the next stage of the climb- ABC – 5700m.

Elia shoots off with our climbing sherpa Dawa Tenzing, and I walk at a snail’s pace with Namgyal Sherpa and Passang Sherpa – our cook. Namgyal, a Buddhist monk, is a quiet man of small build, has a shaved head with a warm-smile. Do not let this monk fool you. He is incredibly powerful, and has almost half a dozen Everest summits under his belt. Passang, our cook, is as one would imagine a Sherpa cook to be: He is round and cheerful. Always smiling and will find the happy side to everything in life. He is also an excellent cook, and makes some mean apple pancakes.

3hrs into our walk to ABC and I’m out of breath (this is getting old). What is going on K? You’ve trained for this all year. Push it. So I do. I’m clearly battling mentally. I turn to Passang. Are we far? Passang laughs. Yes we are my friend, not even half way. Shit. Why? It’s not me. I fight. It’s me again. I fight some more. Ok I’m back. Lets smack this and get to ABC. I’m out of breath. I need a break. Water. Passang….. Tell me we’re close. 2 more hours Kheiry. I get on the radio: “Elia Elia Elia, over”. “Yo K… whats up?”… “Dude. This is one frikin’ nasty walk”. “Hehehe, yeah I know. Wait til you get here, real luxury pal. Enjoy the rest of the trip up, OVER”. “Yeah yeah.. Kheiry OUT”.

Big ridge to get to. We switch back it over moraine. Top out. Hardest part is over. One step in front of the other. You can do this. I see tents in the distance. I’m here. All the big commercial banners. This is it. Welcome to major league mountaineering. IMG (int’l mountain guides), Russell Brice’s HIMEX (Himalayan Explorer), Jagged Globe from the UK, Victor Saunders, Amical, 7 Summits Club, and the list goes on. People and expeditions I’ve been reading about for years. Hero’s. 8000m climbing Legends. I’m amongst them. I felt a part of it. It was something I’d always wanted to be amongst. And now that I’m here, all I can think about is catching my breath and collapsing into my tent. It takes another 10mins to get through the village that is ABC, in the distance I see our tents. The Barclays Capital and Climb 4 Lebanon banners flying high. I’m home.

I walk into the mess tent, Elia is looking very serious. I’m hyperventilating again. For no reason at all. I’m sitting still. Why am I hyperventilating? Elia looks at me, dumbfounded, maybe also a little hypoxic because of the altitude. He is Human too ultimately, and must have felt the effects somewhat. But why am I so out of breath. I know the air is thin, but its still only 5700m, and last time I was at that altitude – the summit of Kilimanjaro last August, I was running laps up there. Why why why? I take things easy. I calm down. I breathe again. We settle a little more. I find my tent. Make it my new home. Same routine: Mat number 1, Mat number 2, Blow up thermarest mat number 3. Ok matting done. -40 degree sleeping bag, unfurled. First aid / medical kit laid out on the side. You’re ready for anything K. Flash light. Back up flash light. Reading material. Tissues. Red P bottle with my home made skull and cross bones drawn on it in black marker “DO NOT DRINK”. Ok. Back out the tent. Out of breath. Crap. Ok. Back to the mess tent. Time for a drink. Rehydrate, eat and rest. Elia is looking at me quizzically. Why is he looking at me like that?

“K are you ok? you don’t look right.”

“I’m fine. I’m just out of breath.”

You better call Ramsey (our expedition doc).

“ok”. Then I fall into a fit of hyperventilation. I’m heaving. Gasping. I was sitting still… How could I be hyperventilating again? ok something absolutely not right here. Elia sets up the satellite and we dial Ramsey. No answer. DAMN. Now what? “Elia what time is it in Canada? can we call one of the other doctors?” … No it’s too early. I try Ramsey’s sister… I’m heaving by now… she picks up! thank god…

“IS… Ramsey……. Next…… to you?”

“No he’s at the airport, are u ok?”

“No I’m not.”

“ok I’ll try and get him to call you asap”

Line cuts.

I fight again. For breath. I now realise that things are not the way they should be, and something is worryingly wrong here. I try Ramsey about 3 more times til he finally picks up.

“Ramsey”

“Hey Kheiry… you ok?”

“Ramsey…. I’m not feeling well”

“Whats wrong, tell me”

“I….. can’t……. breath….. I feel choked. Chest is constricting. Medication is not helping. Something’s not right with my body”

“Kheiry go down. You need to descend immediately. We’re not taking any chances.”

My eyes welled up. I choke back a couple of tears and pass the phone to Elia. He continues the discussion on my behalf, concisely and scientifically. I’m crying. More inside than out. Realising that my dream is over. I hear Elia in the background, discussing me with Ramsey. I’m no longer there. I’m living an outer-body experience. It’s all background noise.

“Yes I agree with you. I totally agree with you Ramsey. That’s what I thought.” Elia sighs. He turns to me.

“we need to get a couple of opinions. but I had a feeling we were going to have this conversation at some point K. I’m so sorry. Lets email Gabriel and Al and see what they say from Canada. We’ll ask some high altitude specialists and make sure we make the right decision. Meanwhile, sit tight and try to sleep. and for the love of god DRINK more WATER!”

I retire to my tent early, 8pm, and sit up for the whole night. staring at the walls of my tent, contemplating what lie ahead. unable to breathe still. hoping things improve by morning. They do not. Elia is waiting for me in the mess tent, lap top open and asks me to sit down before he reads responses from our high altitude specialists in Canada.

“You’d better sit down for this K”.

Response number one (Elia reads it out loud to me):

Given his performance so far on the pre climb = no way in hell that he will make summit day on Cho Oyu. It is a bear. No way. Plan accordingly now.

Yes dehydration alone can cause everything you have said including drunken walk and short of breath lying down and poor sleep. Try doing his nurse and force him to drink for 2 days accounting for all his water and making sure he is pissing clear and a lot. But keep in mind:

All respiration problems feel worse lying down including infection – this is a classic sign of pulmonary edema. If this is pulmonary edema he would prob get worse quickly at current altitude or get worse and decompensate and a high altitude.

Drunk walk with preserved hand coordination is a classic sign of cerebral edema but usually the patient is really sick and starts to deteriorate very fast.

Not sleeping like that is just plain and simple not acclimatizing.

All said if he looks alright at ABC and rehydration helps he can prob go up part way with you but given his performance on the pre climb he will not summit. If he looks sick start working on plan B right now because if he deteriorates Tingri might even be way too high for him. Make two plans now. One to send him down now if he is agreeable and realizes he is not going to go up much higher. And send him with reliable peeps. The second plan is that this will be a middle of the night exodus and oxygen and porters might be required.

Good luck.

——–

Its over.

( )

)

But just for fun… Lets look at response number 2:

Hi Elia,

Specialist thinks (and I agree) that K has probably a beginning of pulmonary or cerebral edema. Losing his balance is the key element here for edema. All the previous problems you mentioned equals altitude sickness. He is not properly acclimatized about 4500m. Not sleeping doesn’t help so now altitude sickness goes to step 2 which is edema. Recommendation: give him 4mg dexamethazone every 6 hours. This will help reduce the edema. Stay on diamox 1/2 tablet every 12 hours. Drink a t least 4-5 litres. Most importantly , send him down as soon as possible to an altitude he felt good which seems to be Nyalam. If weather gets bad and he is still short of breath, put him on oxygen.

If he descend with a Sherpa, make sure they have all the necessary medication including oxygen bottle.

Sorry for K.

I’ll check my mails if you need more assistance on this issue.

Let me know your decision.

——-

I look Elia in the eye

“Time to plan my descent I guess”

Elia sighs… says it wasn’t meant to be like this. I was meant to go to the summit. You sure?

“I have no choice. If I stay my condition gets worse. I feel something is wrong with my body and I don’t care enough about this mountain to ignore my intuition on this.”

We make arrangements. It’s already 11AM by then, and probably a long shot to head down same day. We had so much packing and planning to do, including arranging emergency vehicles to be on standby as high as the road can take these cars to reduce the amount of impact upon my descent the next day.

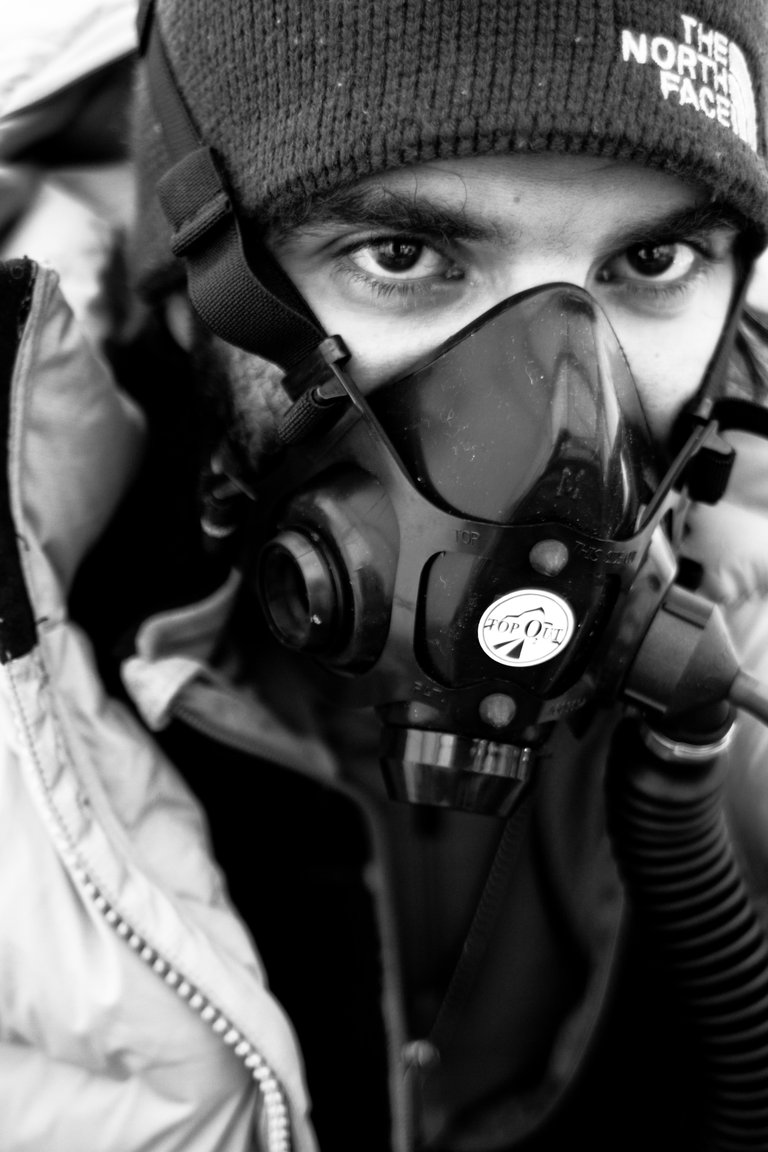

We immediately rigged an oxygen tank, and I put my mask on for the first time on the climb. The mask that I was meant to wear on my summit attempt is now the apparatus that is going to keep me alive.

Elia looks at me. As I breathe through the apparatus, I sound like Darth Vader. The tent now sounds like a hospital A&E room with all life support machines on full blast. I slip the pulse ox monitor onto my finger so we keep regular tabs on my oxygen levels and heart rate, which is beating at an average of 120 beats per minute at complete resting rate. Pulse ox is showing a reading of 78% oxidisation in my blood – normal at sea level is around 99-100%.

Though these are normal levels for this altitude… I start to worry.

What are the symptoms of Pulmonary Edema?

Symptoms: at least two of:

– dyspnea at rest

– cough

– weakness or decreased exercise performance

– chest tightness or congestion

Signs: at least two of:

– crackles or wheezing in at least one lung field

– central cyanosis

– tachypnea

– tachycardia

(*Source Highaltitudemedicine)

I had all the above. It creeps up on you, because all are subtle. And all can be associated as “normal” at high altitude. And it’s easy for you to brush it off and say… “I’ll just tough it out”.

In my case, the hypoxia of high altitude caused constriction of some of the blood vessels in my lungs, shunting all of the blood through a limited number of vessels that are not constricted. This dramatically elevated my blood pressure in these vessels and results in a high-pressure leak of fluid from the blood vessels into my lungs. Exertion and cold exposure also raised the pulmonary blood pressure and contributed to the worsening of HAPE.

This is where things become dangerous. I was showing signs of HACE.

A bit of background:

Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS) is a spectrum of illness, from mild to life-threatening. At the “severely ill” end of this spectrum is HACE – High Altitude Cerebral Edema; this is when the brain swells and ceases to function properly. HACE can progress rapidly, and can be fatal in a matter of a few hours to one or two days. Persons with this illness are often confused, and may not recognize that they are ill.

(I’ll be fine… I’ll just tough it out)

The hallmark of HACE is a change in mentation, or the ability to think. There may be confusion, changes in behaviour, or lethargy. There is also a characteristic loss of coordination that is called ataxia. This is a staggering walk that is similar to the way a person walks when very intoxicated on alcohol

(on more than one occasion this happened to me).

THE BATTLE PLAN:

Get off the mountain ASAP.

We get ready for my long-sleepless night ahead. I get into my bag; strapped to my oxygen, pop dex – a very powerful steroid that helps buy time with HAPE and HACE. And I pray. And hope. That I will get through the night, and still be able to walk the next day. I feel chest pains, and hear a gurgling sound in my right lung when I’m breathing. They must be filling with fluid. I pray not.

I get through the night and look out my tent… It’s what a winter wonderland would look like in Hell. I had to shovel my way out of my tent and I couldn’t see further than 10m- White out- Blizzard. How the hell am I going to climb out of this one as weak as I was. On a normal day it would just be a tough day out. When you can barely put one foot in front of the other and there’s a full scale Himalayan storm outside, you’re simply buggered.

6AM: We need to get going.

6.30AM: Breakfast. Eat well. Could get nasty.

7.00AM: Delayed… Elia looks at me. “K… the weather’s no good, maybe we should postpone this another day”… I feel my right lung start to wease, and I’m out of balance… I need to move.

7.30AM: Last second preparations, packing.

8.10AM: We set off into the storm.

I’m wearing thermal base layers, my fleece, a big yellow down jacket, a beanie, over my beanie are the oxygen mask straps, over my eyes are my Julbo all-weather black goggles (like a ski-mask). I’m wearing weatherproof pants, and my mountaineering boots with no crampons.

We start walking along the ridge to wear it will drop in altitude, followed by a really steep hill we need to climb with semi-frozen water running down it (you need to watch your step here, wrong move will result in your foot going through the thin ice, and getting your feet wet… get your feet wet and you’re finished). Once the hill is climbed, there is a road. A road they have been building for cars for over a year now, a road that is meant to lead to ABC one day. A flat surface… which should lead all the way down to mid-camp. We radioed in for an emergency 4×4 rescue vehicle to meet us as far up this road as possible. So in my mind… “Just get to the road K”.

So this all sounds relatively simple right? Easy peasy? No… not easy peasy. Not when there is a full-scale storm blowing in the midst of a land rescue.

With Dawa in front and Elia and behind me I had less to worry about. Dawa broke trail ahead, with each step his foot sunk to his knees into the snow, and Elia kept a close watch on me. If I stumbled he’d catch me, if I swayed he’d keep me in line, if I stopped he’d make sure I’m hydrated. I wore a down jacket, he did not. Every time I stopped he froze, and I felt guilty. I know it has been a recurring issue here, but the fact is…I was continuously out of breath. My lungs were filling up with fluid, occasionally I’d have to spit, and the sight of it being pink/red on the snow freaked me out even more. I had HAPE and I had to get the f off this mountain. I’m sure Elia saw it too, and I was too scared to bring it up.

My legs were holding well in the deep snow, occasionally they would waver, but only occasionally. I was well trained for this and knew they’d go the distance. The dex was working strong and giving me the power I needed. Hail, snow, hail, snow… Pain. Breathlessness. I yell at Elia through the wind:

“WHERE IS THE EMERGENCY VEHICLE!?”

…

“You want the truth K?”

“Yes”

“There won’t be one. The Chinese Liason Officers don’t care. Please keep moving I’m freezing”

I sigh.

He continues…

“You will need to get out of here on your legs”

I turn.

I fight.

I tell myself I’m not going to give in. Not today.

I want to stop and give up. I’m weasing. My lung is weasing. I need to move.

It’s slow going… I start to finally recognise landmarks that mark my proximity to mid camp.

Elia turns to me… “this is it K, the homestretch. It’s all-mental now. Fight”

30mins go by. I start to make out the shapes of the Yak-Poo Tents. Better yet. I see emergency 4×4’s there too. I’m saved. I also see Jeremy waving at us. Home. Home dry. I’m 20 metres away and fall to my knees, pole in hand, thanking the great architect for the second chance he has given me. I’m saved. My face is awash with tears. Tears of hope, gratitude, exhaustion, fear, cold, relief.

Elia helps me back up and into the tent. Filled with Tibetan road-workers, not at work because of the storm. Staring at me in my breathing apparatus. Everything becomes fish-eyed. All I see is people staring. Jeremy sits me down on the couch and hugs me. I burst into tears again and I’m shaking. I’m alive. Jeremy gets emotional. Elia is coordinating everyone. I’m in shock. Tea gets brought to me, I forget for a second I still have an oxygen mask on my face and try and drink some tea. Still in shock. Everyone laughs. I get it right on my second attempt. Faces still staring. Everyone is smoking. The tent barely has the same visibility as the storm.

Its all flash backs now.

The Chinese rush me into the car shortly after the tea, and I get a moment with Elia. I want to say thank you, for risking his life to help get me out, to say good luck, be safe, and please don’t take any unnecessary risks. Thank you for putting this whole thing together. Thank you for being my friend when I needed you most. Thank you for not laughing at me when I told you my dream was to climb Cho Oyu. Thank you for believing in me. And thank you for saving my life Elia.

All that I managed however were tears and a hug. We rubbed our foreheads together and we understood what had to be done:

My doctors in Kathmandu tell me I’m lucky to be alive. That had I left it another 24hrs I would most likely not be here telling you my tale.

For this second chance I am grateful.

As I write this Elia is standing on the summit of Mt Cho Oyu after having defied all laws of gravity. He had no purpose left on the mountain he told me. But there is always a purpose. How do I feel about that? Wish I was there… to be honest. But I also like being alive, so I think it’s fair.

Season Stastics (So Far):

200 climbers

24 summits (including Elia & Dawa)

2 Dead (one hit by a serac at the ice wall, and the other was due to an avalanche that enveloped him in his tent/sleep). One Czech and one German. Nobody knows their names as they were alone. God rest their souls.

(*First hand from the mountain + exweb)

I leave you with on of the greatest mountaineering quotes of all time from George Leigh Mallory on climbing Everest:

‘It is no use’. There is not the slightest prospect of any gain whatsoever. Oh, we may learn a little about the behaviour of the human body at high altitudes, and possibly medical men may turn our observation to some account for the purposes of aviation. But otherwise nothing will come of it. We shall not bring back a single bit of gold or silver, not a gem, nor any coal or iron. We shall not find a single foot of earth that can be planted with crops to raise food. It’s no use. So, if you cannot understand that there is something in man which responds to the challenge of this mountain and goes out to meet it, that the struggle is the struggle of life itself upward and forever upward, then you won’t see why we go. What we get from this adventure is just sheer joy. And joy is, after all, the end of life. We do not live to eat and make money. We eat and make money to be able to enjoy life. That is what life means and what life is for.”

ENDS

Congratulations @mambojuice! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!

Well written