We were a long way from Hemet. Backstage at London’s Brixton Academy, half-empty champagne bottles in hand, the wild dreams of hip hop stardom we’d been cultivating since growing up in the Californian San Jacinto Valley were coming true. We were the buzz of the music business: the certified, guaranteed next big thing. We’d partied with Muse, played football with Rod Stewart, got drunk with David Walliams and accosted Madonna.

Now, our band, the punk/hip-hop hybrid Silibil N’ Brains, which I formed with my best friend in Huntington Beach, had just opened for D12, Eminem’s crew, to a British audience who adored us. We’d been High-fived by proof, Eminem’s consigliere, and swapped tour stories with Kon Artist, Bizarre, Swift and Kuniva – our new friends and peer group. We had a recording contract with Sony potentially worth millions, a management deal with one of the biggest players in the game Jonathan Shalit, and now Proof was shepherding us through the throng in the dressing room towards n unmistakable, pale, peroxided figure. “Hey Em” he said. These guys opened for us tonight, they’re dope. Eminem extended an affectionate fist bump in greeting.

We were going all the way. Nobody thought or said otherwise. The fix was in. We were beyond the velvet rope. We were going to be superstars. There were, I remember thinking that night in the luxury tour bus, only a couple of minor obstacles that could block our path to fame and fortune. We weren’t born in Hemet, and we never lived in Huntington Beach. In Fact, I’d never even been to America. We were not Silibil N’ Brains. We were Billy Boyd and Gavin Bain and we’re from Dundee Scotland.

There’s two problems with lying. One is that you can’t just lie once. Dozens, hundred, thousands of other lies must be summoned to support the whopper you started out with, and they can become kind of difficult to keep track of. The other is that people believe you – and the bigger the lie you tell, the more convincing it seems to be. When Billy and I embarked on our absurd scheme, we comforted ourselves, at some subconscious level, with the reassuring knowledge that we’d get rumbled fairly quickly and no real harm would be done, to us or anyone else. If I had been told in advance that I’d end up alienating everyone I knew, blowing a quarter of a million pounds, being hospitalised eight times, having a total of 60 stitches put in me, overdosing twice, attempting suicide once and winding up in sperm banks and as a part time escort agent to clear a sinking sand pit of debt, I might have thought twice. Might have.

But It seemed, as so many calamitous schemes do, like a really good idea at the time. Anyway, we’d tried being ourselves and it got us nowhere. In 2001, our group, then a trio of myself, Billy and another friend called Oskar, had come down from Dundee, where we had developed a cult following for our riotous live shows and unabashedly Scottish rapping, determined to show London what we had. I’d seen an advertisement Polydor records had placed asking: “Are you the next Eminem?” My only answer to that was a dementedly certain “Yes!” We’d wouldn’t have made this 13 hour bus journey otherwise.

The audition, in front of three A&R executives, went well for all of 15 seconds. We launched into our punchline heavy, multi-syllabic rhymes, which had been bringing houses down back home. And then, one of them started to chuckle. And then another. It was as if someone had laced the room with nitrous oxide. It was humiliating. Soon, they were all at it.

They shut our backing track off and, wiping away a few tears, suggested to us that Scottish Rap was, as a concept, about “as marketable as soccer boots for cripples” they mocked. We were angry but not deterred. We took our demo to Wordplay, a London based underground hip hop label known for its credibility and unstinting commitment to the boldest new talent. “You sound like the Rapping Proclaimers,” they told us. Now, we were deterred. The bus ride home was even longer, a torture I wouldn’t recommend enduring after your dreams have been crushed.

Most people – that is, the sane ones – would have given up at this point, and resigned themselves to whatever morsels of hometown notoriety they could forage. Not me: I was obsessed, to the extent that I remember telling my long-suffering parents that I would kill myself by my 25th birthday if I hadn’t made it in music by then. I retreated into my room for weeks at a stretch, rarely eating, barely sleeping, never washing, doing nothing but creating beats and backing tracks on my computer, and filling notebooks with new rhymes and lyrics, not a few of them reflecting on the cloth ears and utter bastardry of everyone in every record company office in London. I came up with dozens of songs which were, in my admittedly biased opinion, brilliant. I also – perhaps due to sleep deprivation, lack of exposure to sunshine and over exposure to Pot Noodles and mind-altering substances – came up with an idea about how this material should be presented to the world.

I explained it to Oskar. “Who are we kidding?” he asked, astounded. “I’m sorry, Gav, I can’t do it.” I explained it to Billy. “I dunno man,” he replied. “Sounds a bit loco.” Oskar and Billy were two very different people. When Oskar said that, he meant no. When Billy said that, he meant yes.

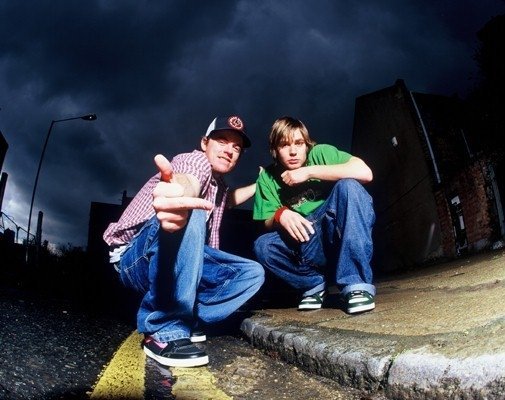

The plan was as elegant as it was ridiculous. We’d return to London, but not as a trio of awkward, supplicating Scots . We’d go as a pair of swaggering, insouciant Americans. We researched our roles thoroughly, by which I mean that we watched hours and hours of American television. In the two weeks before hitting London we’d put exhaustive practice into our accents and mannerisms, spending every waking minute rapping, talking, even masturbating in American accents. We read extensively, in between the lines, about the industry, gave ourselves the Cali make over swapping khaki camouflage of the underground hip-hop scene we usually moved in with the lurid, luminous colours of commercial rap and MTV-friendly R&B. We looked like Ali G had thrown up over us, but we looked like the part we needed to play.

Even now, it’s difficult enough for me to believe how quickly and easily London rolled over. For those unacquainted with the degree to which the music business is fueled by ego, guesswork and blind terror of missing out on something, it would seem incredible. Happen it did, however. If I learned one lesson from the entire farrago, it was this: contrary to popular wisdom, you can bullshit bullshitters.

We managed to blag a slot on the bill at Madame JoJo’s, a Soho club normally patronised by drag acts and people who dressed like drag acts. That night, however, it was largely populated by serious, scowling people who addressed each as “blood”. Nevertheless, our nerve held our show went over well, and afterwards close professional relatives of the people who’d written us off as the rapping Proclaimers were forcing their cards in our pockets. At half past 10 the following morning we were rapping to a boardroom full of Island Records employees.

We didn’t have to – we ended up being able to take our pick. The music business is an echo chamber, and the buzz around us reached people quickly. One of these was the impresario Jonathan Shalit. He managed stars of musical theatre and mainstream television, which didn’t impress us. He also managed Jamelia and Big Brovaz, which did. When he appeared at the meeting he’d demanded, I thought of the Penguin from Batman, only dressed as a Hollywood pimp, all shimmering silk and glittering bling. While we didn’t get the impression that he knew or cared much about our music, we did get the impression that he was serious about making himself richer, and that he thought we could help him do that. He advanced us £70,000, rented us a house, and put us in our first professional studio.

Our excitement at the money and the dramatic improvement in our accommodations – we’d had £350 between us when we’d arrived in London, and had been living on the floor of my sister’s studio apartment in Walthamstow – was tempered by the first proper rumblings of the apprehension that would, ultimately, destroy everything. Because we weren’t kidding anymore. We were spending someone else’s cash – and quite a lot of it – on an illusion. And, we knew but never said, there was no way the fraud was sustainable. If we did get a deal, and we did get a hit, then the moment our dreams came true would also be the moment they all unravelled – if we opened our yaps once on television, the news that we weren’t hip rap dudes from California, but a pair of chancing tossers from Dundee, would be all over the internet before we’d closed them again. We’d be laughing stocks. We’d be finished. We’d be sued. We might even be arrested.

Denial is a powerful thing, however and soon we were believing our own hype – even though we were the ones who’d spread it. By night, the drink and the drugs and the attention being lavished on us helped us forget the predicament. By day, we worked furiously, telling ourselves that we’d create something so brilliant that when the truth inevitably emerged, not only would it not matter, but people would think we were even cooler, for having made an amazing record and taken the business for an almighty ride as well. We convinced ourselves so completely that we even managed to keep straight our stories, and our faces, when Jonathan took us to where he’d decided we needed to be: Sony Music.

Of all the shows we ever put on, it was probably the best. We bounded into Sony’s headquarters, greeting every employee with a “Yo” or “Hey,dude,” and the enterprise in general with whoops of “Silibil N’Brains, in the motherfucking building.” Strange how easy it is to slip into the vernacular of the generic America rapper, when you’ve never got any closer to the ghetto than watching MTV, but we acted like a beam of bright Californian sunshine descending to brighten everyone’s miserable English winter’s day – and, not for the first time, we realised that everyone wanted to believe that that’s exactly what we were.

Fifteen people were crammed eagerly into Sony’s boardroom. A bottle of champagne was cradled in an ice bucket. A contract lay on the table. It guaranteed a £50,000 budget for our first two singles, and over £100,000 for our debut album. Beyond that, the people in the boardroom talked of Europe, America, Asia and Australia and the millions they were willing to spend to make it happen for us in those territories. Please, I thought, let neither of us say “Aye” to anything by mistake. I grabbed the pen off the table and signed the thing before anybody – myself especially – could change their minds. At 1:30 in the afternoon of February 13th, 2004, I was officially a Sony recording artist. Billy and I went out and celebrated accordingly.

I remember lots of free drinks and falling unconscious in the women’s toilets of a west end club. Then, a fight with a bouncer a chase and a cab ride home. I rummaged through Bill’s pockets as he lay slumped on the doorstep in order to pay the driver. Then darkness.

The next day I woke up in a North London hospital. A nurse was telling me that I had alcohol poisoning and that my stomach ulcer (which I didn’t even know I had) had nearly burst. Before she moved on to the next bed, she leaned towards me, her voice flat and dismissive saying, “You’ve been very lucky young man.”

She had a point. There I was lying in a hospital bed with old men clinging to life next to me and I had a big smile on my face, fantasising about what was to come: The groupies, the week-long benders, the VIP parties, hanging out with Madonna. I sank back into the mattress. Phase 1 of Plan A (in time honoured fashion, there hadn’t been a Plan B) had worked.

But Silibil N’ Brains did not, you’ll have noticed, become superstars. We didn’t, in the end, even release a record. This was partly to do with the internal politics of Sony, which were pressurised further by the general tottering of the music business as a whole, but it was mostly, to be honest, to do with us. Having pulled off the heist, and developed a taste for living on the proceeds, I was desperate not to get caught, and desperate people tend not to think terribly straight. Our first TV appearance, on MTV’s TRL, had given me a fright – logging onto a hip-hop website later that night, I cringed at a bewildered comment from someone who was certain he’d been to school with Billy in Arbroath, and someone else who could have sworn he’d once had a fight with me in a chip shop in Dundee. To my relief, the whispers went no further. But I knew they would, and sooner rather than later.

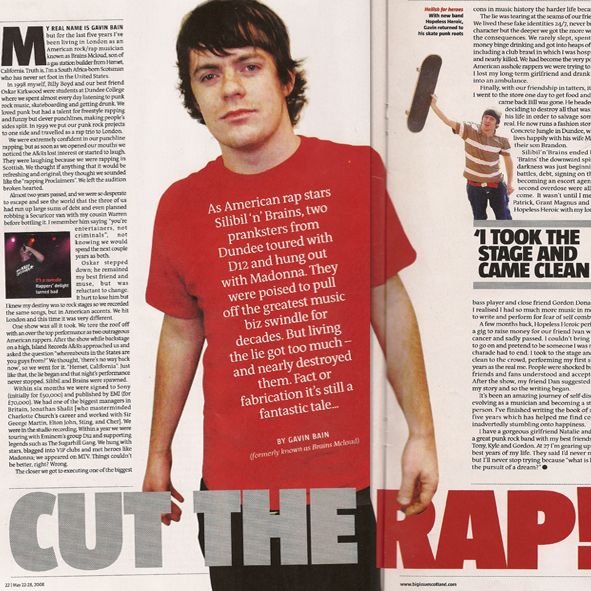

Beginning to panic, I figured that while we wouldn’t survive as rap artists after being outed as Scotsmen, we might get away with it by reinventing ourselves again before anybody blew the whistle. Then, we would, or at least might, look like chameleonic geniuses and brilliant situationist pranksters, rather than laughable imposters: more KLF, less Milli Vanilli. We added three more people to the band and informed our management and our label that we were now, more or less, a punk rock group. Jonathan, mercifully, found this amusing. Sony found it less so.

But we toured, and that went well. We kept rehearsing and writing, and that went well. And I kept drinking, more and more and more, and that went less well. It’s not a good sign when your first thought on waking is “At least it’s a different hospital”. Worse than any of that, my friendship with Billy was collapsing under the weight of the deception we were engaged in, and beneath an additional avalanche of drink, drugs and general ill-living. Things got to the point where it seemed an actually smart career move to record a hip hop/punk cover version of Kenny Loggins’ Footloose. Bill got fed up with the lies, and cheating on his childhood sweetheart and so decided to head home to Dundee to make amends but not before we attempted to beat the living daylights out of each other.

In contrast to the high ceremony and grand debauchery that heralds the signing of a contract, there is no official notification attending your release from one. You just notice, one day, that everybody has stopped calling. Then you notice, generally that same day, that when you call them, you can’t get through, or they’re in a meeting, or they don’t return your messages. It was the most crushing of ironies - though I didn’t appreciate the humour of it at the time. The fraud we’d perpetrated, and worked so hard to maintain, was now an irrelevance – just like us. I could have appeared on national television in a ginger wig, a tam o’shanter and a kilt, blowing Runrig songs on the bagpipes, and nobody would have cared.

I felt nothing at first but then fear and panic set in. I couldn’t handle failure, I couldn’t go back home and I couldn’t make music in London. So I became a hermit, addicted to painkillers. It took me a while to realise after two years of constant pressure, touring, partying, lying and fighting we were lucky to get out alive. It’s been hard to make sense of the last few years, how I got it all, lost it all and won it all back again. Despite everything that happened to us, I’ve come to realise that Silibil N’ Brains were not con men, we were magicians. And it’s not over yet.

You see, your talent is always your life line, the extra bullet in the chamber when you’re in desperate need of one last shot. My talent took me from the bedroom to the big stage on one incredible journey where I discovered the truth about music, marketing and the confidence I needed to become the real artist I always wanted to be.

Thanks so much for reading my first Steemit post. I fully intent to blog regularly this year and use the platform as a home for my articles, memoirs and diaries moving forward. So feel free to follow me on here.

Until next time, do what you love, create what you like, make a difference and most of all... keep rocking in the soon to be free world.

Gavin aka Brains

This post has been voted on from MSP3K courtesy of @Scuzzy from the Minnow Support Project ( @minnowsupport ).

Bots Information:

Join the P.A.L. Discord | Check out MSPSteem | Listen to MSP-Waves