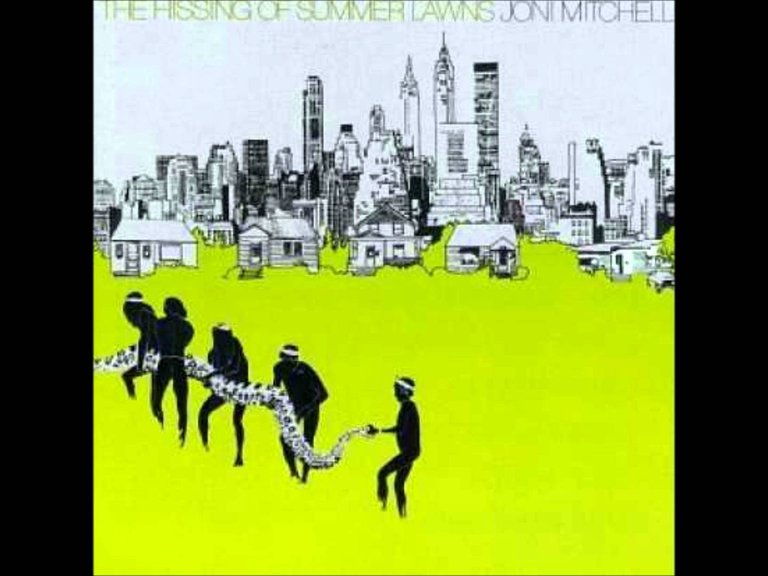

Album Cover

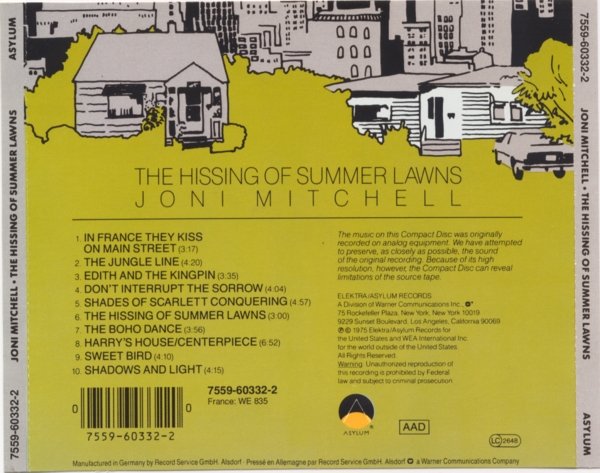

Back of the Album Cover

A PREVIEW INTO THE BOOK

The Boho Dance, song # 7 on the Album, saw Mitchell defining herself in that moment, and expressing how her truth differed from the attacks levied against her by both the establishment (the controllers of the status quo that she was being accused of being a part of), and the Bohemia movement that labelled Her Album Court and Spark as a “sell out”. Through the eyes of many, the “fact” that Mitchell had moved from the artistic, semi-rural community of Laurel Canyon and into the exclusivity of a Bel Air mansion was the height of hypocrisy. Adding to that “fact” was that Court and Spark sounded slick and was a massive commercial success, for many there was a zero chance that the album could be viewed with any sense of objectivity, which is beyond sad because when the “cause” (no matter how noble or not) is more important than the “substance”, then black can become white and up becomes down! Many of the song’s lyrics and musical styles on “Hissing” were purposefully designed by Mitchell to point out the contradictions in her critic’s arguments. Thus, most of the musical progressions found on this album were structured like "unanswered questions" by Mitchell, flowing along with purpose and style, but never finding a logical conclusion (think of the beginning and end to Harry's House)! And this musical approach, of course, was perfectly synchronized to the album's lyrical tales that laid out so many "modern tragedies" of misunderstanding, while NEVER coming to a resolution...and the Boho Dance was the best possible example of this musical question mark...the eternal conundrum that is organized society...damned if you do, damned if you don't...

"Chaka Khan once told me my chords were like questions, and in fact, I've always thought of them as chords of inquiry. My emotional life is quite complex, and I try to reflect that in my music. For instance, a minor chord is pure tragedy; in order to infuse it with a thread of optimism, you add an odd string to the chord to carry the voice of hope. Then perhaps you add a dissonant because in the stressful society we live in dissonance is aggressing against us at every moment. So, there's an inquiry to the chords comparable to the unresolved quality of much poetry."

Joni Mitchell

However, there was another aspect to this particular song that referenced Wolfe’s book, The Painted Word. Mitchell was in support of Wolfe’s viewpoint of the modern visual art scene to the music world. Wolfe criticized the “downtown” visual artist for the “mating ritual” they performed with the business world (the Boho Dance?), where they spurned bourgeois values and traditions in their work only to simultaneously contradict themselves by possessing a “definition” of their own success as determined monetarily by these same wealthy, “uptown”, bourgeois elites. To Mitchell this was the hypocrisy, or the selling out of the artist, not someone who explored different artistic tones and expressions, and who happened upon success. Joni Mitchell NEVER created an album that was designed to “sell”, like any true artist, she simply produced what was in her mind in that moment. To Mitchell, as with most of painting’s “Masters”, she was constantly moving forward in her artistic progression, never was she complacent or acceptant of what she had done...if she was, David Geffen would have persuaded her to create Court and Spark parts II and III, instead of the impossibly difficult "Hissing" and Hejira.

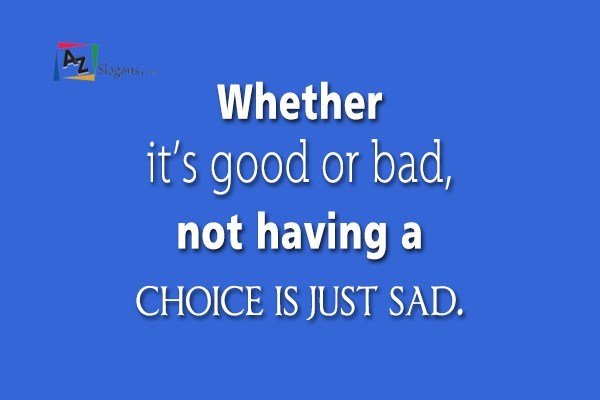

Thus, the Boho Dance was a complex and layered narrative that explained her success with Court and Spark as “accidental” and her ensuing move to Bel Air as “eventual”, nothing more. This was simply a progression in her career that allowed her to see the world from the perspective of the one percent, versus than merely speculating about it. Mitchell never “embraced” that elitist lifestyle and mindset, rather she examined it and then scathed its glaring contradictions…but here is the kicker, she did the same thing to the “Boho” world as well. This open-minded approach of understanding things as “this” AND “that” defined the “Hissing” album. All of her societal criticisms were never completely “one-sided”, either in total favor or disdain. Mitchell was that rare and enlightened human being that could see the bigger picture from the smallest brush stroke, as well as the entirety of the whole canvass. She not only understood the difference between comfort and contrast, but the need for the difference. All life is blessed with free will, and as such, CHOICE in the moment defines what all life is about. Sometimes a person can feel like accepting light, happy, “folky” and free moments into their life that encourages flow and contentedness…this doesn’t define them for an eternity, rather for a moment, or a collection of time. That same person can suddenly change and desire more capitalistic success (and the contrast that goes along with it), resulting in a more celebrated but complex life, largely dependent upon the "critiques" of others. Again, this doesn’t define that person as “difficult”, its just an expression in that moment.

Consistent throughout the album, The Boho Dance didn’t solely portray the one percent as just greedy and controlling, but also as victims of their own beliefs. The same went for those Bohemian musicians who outwardly shunned material wealth and possessions, but nonetheless (as the visual artists that Tom Wolfe described) allowed materialism to dominate their own definitions of what success was and wasn’t; thus, encouraging themselves to romanticize their existence within the world of capitalism (defined by lack) as sacred, virgin or somehow holy. Both sides of the coin were equally conflicted, each with their “virtues” and self imposed prisons; and what unified them through Mitchell’s eyes was their slavery in becoming beings that judged everything as “this” OR “that” instead of “this” AND “that”. And isn’t this, ultimately, what the world “out there” has become today? A series of “good” and “virtuous” nations threatened by "bad" and "wicked" terrorists out to kill freedom? This is what the controllers of the status quo would like everyone to believe, because in doing so we place OURSELVES into a kind of prison cell, where everything in the world becomes a dichotomy.

Muslim-looking people (whatever that means) must be “bad” because most of them are, or support, terrorists, right? Any human being listening to this drivel, who wasn't living in a constant state of fear, would laugh at such a belief; however, there are hundreds of millions of “good” and “decent” people around the Earth who actually believe these incredibly limiting notions. Why? Because they have been brainwashed into believing that the world is black or white (“you’re either with us or for the terrorists”), that differences in human beings are to be feared instead of celebrated, which invariably leads people into even more narrowed beliefs and a perpetual state of fear and doubt…

Down in the cellar in the Boho zone

I went looking for some sweet inspiration, oh well

Just another hard-time band

With Negro affectations

I was a hopeful in rooms like this

When I was working cheap

It's an old romance-the Boho dance

It hasn't gone to sleep

The opening verse was styled differently from the rest of the song, it was simple and somewhat innocent, both in it's music and lyrics reflecting upon the “Boho zone”. The first two lines delineated Mitchell’s “coming-home” of sorts to New York, the heart of the bohemian movement in many regards. How did her trip to nostalgia go? She “went looking for sweet inspiration”, but, “oh well” found only “another hard-time” band with Negro affectations”…that’s how it went. Mitchell was implying that the down and out band was soulless, only hinting at what they thought was hip or cool (to emulate a brilliant but hard-luck Black band). She then placed herself in this same room, once upon a time, when she was “working cheap”. So why did she mention the word “cheap” when the circumstances already connoted that image? Because it was a response to the criticisms she had received from the success of Court and Spark. She likened the “Boho dance” to a game that people played with themselves and others to help feel secure with their “current status”, to be okay with their personal circumstances in relation to the rest of the “industry”. She was calling out the contradiction of the “modern” artist, constantly needing to remind themselves that playing in little dives was indicative of integral artistic success, “needing to” because they were also painfully aware that many artists also played to large crowds, in famous venues, to great critical praise and public adulation. They were rationalizing away the fame and success of others by holding true the “sacred musical certitude” that great music was only possible in small settings where an honest connection could be created between the performer and the audience. Thus, continuing the belief that the “old romance, the Boho dance” hadn’t disappeared, but was alive and well.

But even on the scuffle

The cleaner's press was in my jeans

And any eye for detail

Caught a little lace along the seams

In this brief second passage, the scope of the song musically shifted to a fuller and more complex sound, which matched the “bigger picture” thinking of the lyrics. Mitchell shifted the discussion to her own life as she demonstrated her independence from both scenes (the rich, "sell outs" of Bel Air and the sanctimonious and starving within the Boho district). She was still taking her clothing out herself to be dry cleaned while living in a Bel Air mansion; this was obviously at odds with someone who had allegedly “sold out” her artistic integrity for money and acceptance. While the second part of the passage focused on her particular approach to Rock and Roll. “Any eye for detail”, a line loaded with buckshot, “caught a little lace along the seams”. She likened the creation of her music as a complex process, a synthesis, that mixed a lot of thought with cleverly hidden “lace” right along the seams…right where you could see it, if you paid attention. This was Mitchell slyly suggesting that her music was actually still very true to the protocols of the Beatnik era. It was subversive in how it took vastly different musical notions and combined them together in a complex sound that somehow still managed to be attractive and accessible. Everything that Mitchell “stitched” together was done in plain sight, which only accentuated the subversiveness of her musical “heresy”...

And you were in the parking lot

Subterranean by your own design

The virtue of your style inscribed

On your contempt for mine

Jesus was a beggar, he was rich in grace

And Solomon kept his head in all his glory

It's just that some steps outside the Boho dance

Have a fascination for me

The third verse brought Mitchell face-to-face with a denizen of the Boho zone, and in her eyes, a confrontation with the grand contradiction (her “Royal Scam” per se). The first two lines were a reference to Kerouac’s novel, The Subterraneans, with the person she encountered representing the "Boho living below" there by his “own design”. His virtuous style was “inscribed” by his contempt for her PERCEIVED flair. In Mitchell’s eyes, she was being pre-judged by a form of her own creation, Carey, an artist that exalted the virtues of bohemia while waiting for all the impending benefits from success. She was also calling into question his outsider, hip status as a masquerade “by his own design” as he likely longed for the rewards he pretended to abhor. Thus the lines, “Jesus was a beggar, he was rich in grace and Solomon kept his head in all his glory”, here Mitchell refused once again to be boxed into simply one mindset…this OR that. A “virtuous” life could be achieved by both a noble, impoverished man and an enlightened man of great wealth and public power. It was simply that for Mitchell “some steps outside the Boho dance” had a fascination for her. She was both Carey, noble in her praised creations without economic success, and Joni, still connected to her roots even in the face of ignoble temptations. But the people outside of her couldn’t see this, labelling her as a sell-out of sorts simply because of the phenomenal commercial success she happened upon. THIS was the “great sell-out”, the royal scam, artists who judged the success of other artists based upon their relationship with wealth, all the while publicly condemning the contemptuous thought of using art to acquire wealth! This irrational, judgmental mindset is exactly what the keepers of the status quo desire from the art world...to publically disdain the acquisition of wealth, while using wealth as the key indicator of success. In this reality, the rich of the status quo get richer and more powerful, while artists continue to create for the amusement of the wealthy for little in return. Like the teachings of Lao-Tzu, Mitchell was suggesting that all aspects of life were this AND that, and should be viewed from “both sides now”...

A camera pans the cocktail hour

Behind a blind of potted palms

And finds a lady in a Paris dress

With runs in her nylons

The camera in this verse represented perspective, able to see the contradictions within the club, even one as sanctimonious as the Boho scene. “The cocktail hour” implied a time where drinks were cheaper, and while she did wear “a Paris dress”, she also had “runs in her nylons”. She was the paradox of an honest expression. She could be frivolous and uncaring in one moment and then frugal and compassionate in the next…as she was living life now on both sides of the coin…she was this AND that.

You read those books where luxury

Comes as a guest to take a slave

Books where artists in noble poverty

Go like virgins to the grave

Don't you get sensitive on me

'Cause I know you're just too proud

You couldn't step outside the Boho dance now

Even if good fortune allowed

In this fifth verse, Mitchell was commenting further upon the contradiction of the Boho mindset and the danger it possessed to cement beliefs into this OR that. They read books warning against wealth, acting as the grim reaper coming to take innocent minds away from honorable pursuits. Mitchell noted however that these artists who resisted the call of wealth went “like virgins to the grave…in noble poverty”. This implied that as a virgin they never got to taste the experience of wealth and all that it might have brought them. That their beliefs, noble or not, led them to a life of LIMITATION rather than abundance, all in the name of a “noble” belief. Mitchell could tell that her analysis had won a point and struck a nerve (“don’t you get sensitive on me now”) as she admonished the subterranean, “cause I know you’re just too proud, you couldn’t step outside the Boho dance now, even if good fortune allowed”. She ended that verse with a sentiment that she shared with Tom Wolfe, that sometimes “good fortune” happened upon artists, regardless of selling out or not…

Like a priest with a pornographic watch

Looking and longing on the sly

Sure it's stricken from your uniform

But you can't get it out of your eyes

Nothing is capsulized in me

On either side of town

The streets were never really mine

Not mine, not mine these glamour gowns

The opening lines about the priest “looking and longing” at his “pornographic watch” were further attacks by Mitchell upon the hypocrisy of the Bohemian artist, openly rejecting the importance of material wealth, but eyeing and envying it nonetheless. In the second half of the verse Mitchell was saying that she wasn’t trapped in either mindset, she was open-minded and thus free to go from high society in LA to a Boho Club in NY without falling into the trappings of either biases. Money is NOT evil…it is merely an inanimate object that a small group of white men have imposed a "value" upon (backed by nothing)! However, our own personal beliefs about money generate the relationship we have with it. Seeing money as “evil” and thus something ignoble, merely limits that person’s abundance of money…which is fine, if that is the true desired outcome for the individual. But the fact is, a person with lots of money does not universally equate to a societal monster (although more times than not it does); neither does an impoverished artist equate to a noble lifestyle; as in a state of lack (non-abundance) a “beggar” can justify almost any action against the “entitled”. True freedom always seeks to ignore or escape any categorization (“nothing is capsulized in me”); thus, true nobility is to accept both moments of abundance and lack with equal vigor. It is for each individual to determine which reality they prefer and then focus upon that reality. Throughout history there are people who have put abundance of wealth to good use amongst all “classes" of society; while there are many who have lived in poverty who have chosen to withhold their abundant brilliance of intellect from the masses…which is more noble or ignoble? Life MUST be experienced in the moment, every experience must be given its opportunity to surprise or disappoint...because when we always "collapse the wave function" by determining an outcome before chance plays itself out, WE ARE NOT LIVING LIFE, we are only directing our own Groundhog day!

Mitchell abruptly ended the song with the lines, “the streets were never really mine, not mine, not mine, these glamour gowns”. One last time she focused her message upon this AND that, and not one or the other. The dark and dirty streets of the Boho zone, however noble, were never hers to own or be defined by and neither were the “glamour gowns” of Bel Air. She was free…a free woman in New York or Los Angeles to be herself and express her own unique sentimentality with a “Paris dress and torn stockings”…and if that expression was extremely subversive against any stereotypes, hidden by her beautiful appearance and shiny Jazz charts, then all the more reason to celebrate her hipness or cool. She was the exact embodiment of the Boho artist finally being recognized for pure brilliance in a world obsessed with the acquisition of wealth; thus, she was “cooler than cool”, and someone that the current Boho artists could aspire to become. These were the reasons for the “buckshot” found in the song and narrated coolly and slyly by Mitchell’s vocal. Her voice was just nostalgic enough to generate an empathy from someone living without economic wealth and just coy enough to provide the nod and wink to the affluent listener. The song’s music featured both a simple, heartfelt piano melody (played by Mitchell herself) and simultaneously a complex, rich songscape that featured a lush electric piano (once again performed by Mitchell, providing another this AND that statement), with Chuck Findley's Flugelhorn and Bud Shank's Bass Flute riffing throughout. Thus, the music was also exposing the differences from both lifestyles (the Boho zone in NY and the opulence of Bel Air) and yet it also showed how they could work together, seamlessly…and if that wasn’t an alternative and subversive musical thought in the wide world of Pop music, then I don’t know what else was! She left long, meditative pauses within the song allowing the listener to concentrate on certain lyrical passages. This was improvisational Jazz on many levels, and foreshadowed her move towards even more dense Jazz concepts on her three subsequent albums. Mitchell was in the midst of creating some of the most original music ever generated within the framework of Rock and Roll, and because so much of it was completely misunderstood, she was even being attacked by the same “noble” groups that she was actually championing!

For many in 1974, it was simply too difficult a task for them to contemplate that a beautiful and talented blonde waif could be making some of the most original and subversive music ever attempted within popular music; thus, for a brief moment in time, she was being wrongly categorized as yet another artist simultaneously betraying her roots while selling out for the money! Wrap your head around that juxtaposition for awhile and then you can stand inside the heels of Joni Mitchell…for a moment.