"It feels like a murder," as the 21-year-old composer Jones Tarm writes about his showcase with the recent New York Youth Symphony at Carnegie Hall.

Originally he intended to perform his work, March to Oblivion, which many rewarded various awards.

He described his work as "an offering for victims who suffer from violence and hatred of war, totalitarianism, divisive nationalism-in the past and present." The winner of the prestigious First Music competition took on several musical idioms of the Soviet-era Ukrainian anthem and Horst Wessel Lied, the official song of the Nazi party.

In the memo of his concert program, Tarm did not explain that he did that-or why.

In a broad public statement, the Youth Symphony's executive director stated "given the absence of transparency and no permission from parents, we can not display his work on the program".

No less fierce, Tarm says every music has the right to "speak for itself".

He then called the NYYS decision as a censorship action. (However, playing Horst Wessel Lied is still illegal in Germany.)

The question of whether music, a collection of vibrations of sound, can "mean" anything-and if so, how we should answer that meaning-is an obsolete and annoying question, which we still can not answer.

Classical music may have a reputation for being subtle and genuinely courteous, but controversies and scandals overwhelm its history - the continuing provocation of Wagner, or Stravinsky, whose Rite of Spring sparked the most legendary riot in music history.

Here are some classical music works that have caused rioting-for both aesthetic, textual and political reasons-in the last few centuries.

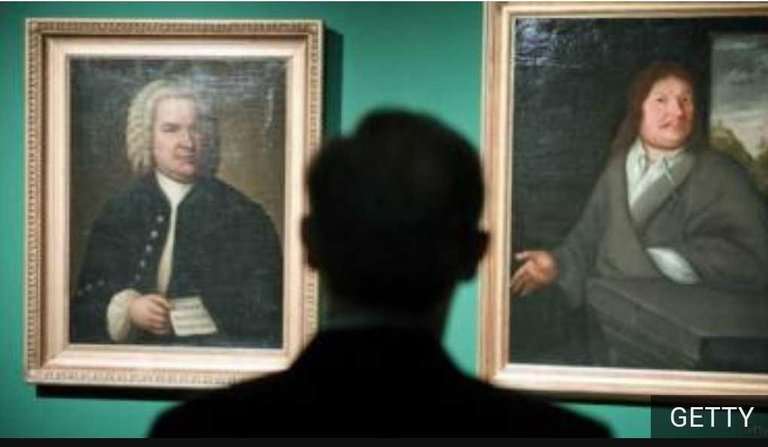

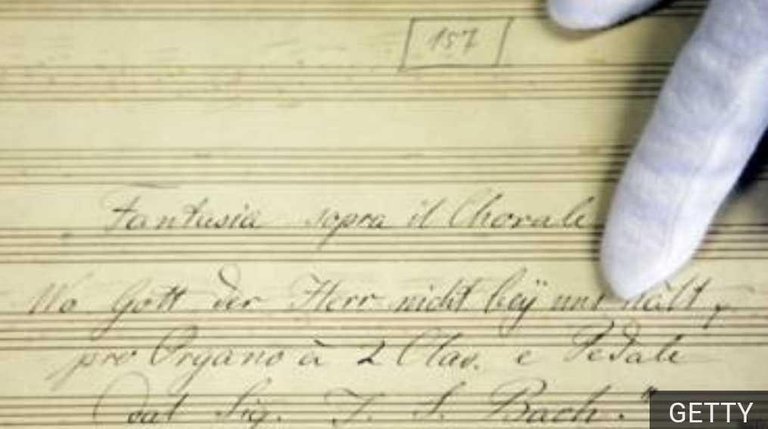

St John Passion by JS Bach (1724)

We would not really imagine this father of classical music as a machinist-though proved in the marvelous biography of John Eliot Gardiner in 2014, we would not consider him a saint simply because he has written such sublime music.

But what he did with the Gospel of St. John, a foundation for the great works of classical musk, leaves some uncomfortable for some.

In 1995, a protest rally broke out at Swarthmore College in Philadelphia, after members of the choir refused to sing what they regarded as anti-Semitic words.

The gospel in question refers to Jesus' enemies as "Jews, Jews, Jews," who repeated 70 times in the 110-minute show.

In 2000, on the anniversary of the 250-year-old composer's death, a demonstration rejected the Passion show at the Oregon Beach Festival, marked also by a rabbi obstructing the event and others resigning from the festival planning committee.

Criticism shifts to debate; Michael Marissen's study, "Lutheranism, Anti-Judaism and Bach's St. John Passion" closely looks at Bach's way of addressing the challenging gospel.

Nevertheless, many commentators refer to the leading expert Bach's view, Robert L Marshall, that St. John Passion "gives voice to the supreme feelings of the human soul (and) does not require the apologies of both the masterpiece and its unrivaled creator . "

Symphony No 3: 'Eroica', a new title replacing 'Bonaparte' by Ludwig van Beethoven (1804)

The story behind Beethoven's third symphonic offering is a legendary story in music.

As the BBC broadcaster Tom Service writes: "Imagine if no incidents are involved, and Beethoven remains in the original plan, and the third symphony is called 'Bonaparte'.

Imagine the various interpretations and analyzes that could lead to the work of drawing the work between Napoleonic projects and humanist ideas.

Napoleonic 'certainly explains how Beethoven put his work - he has even devised a program about Bonaparte's life in the symphonic movements. Until a time in 1804 when he was told that Napoleon had raised himself as Emperor.

Initial offerings for Bonaparte were abandoned; Beethoven announced that Napoleon was a "tyrant", who "would consider himself superior to all others," and substituted his symphonic title to "Eroica".

The symphony was also controversially musical, causing Beethoven's big fan Hector Berlioz at one point to say "if it really is what Beethoven wants ... it must be admitted that this is absurd."

Absurd or otherwise, Eroica emerged as one of the most important cultural monuments of all time.

Parade by Erik Satie (1917)

"My dear sirs and dear friends - you are not just a fool, but a fool without music."

That was Erik Satie's commentary on Jean Poueigh's criticism, which included his music in the Parade, a 5-minute piece written for Diaghilev's Ballet Russes, which also included modern iconoclastic imagination Jean Cocteau and Pablo Picasso.

Poueigh then sued Satie in a bitter court battle-and won.

Known as an eccentric and eccentric composer, Satie used sound effects that were considered radical at the time such as typewriter sounds, clinking bottles of milk, gunshots, fog horns and sirens.

Avant garde? Of course, but the audience at the erdana show in Paris on May 18, 1917 agreed with Poueigh; they cheered, pouted, and even threw oranges at the orchestra.

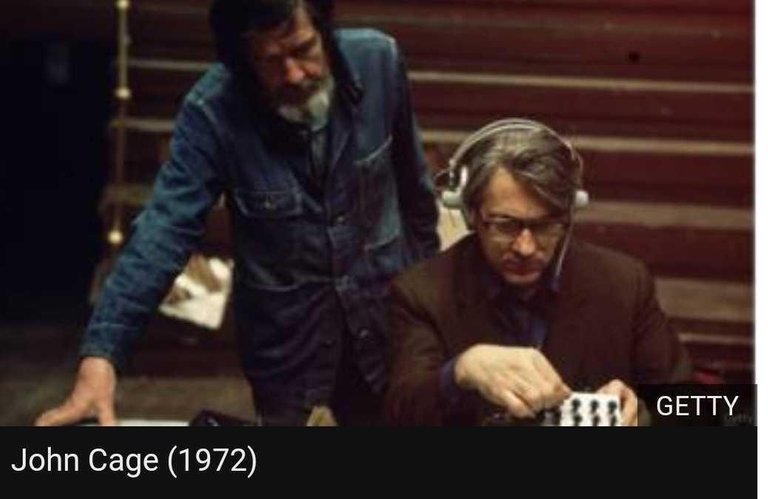

4'33 "by John Cage (1952)

Cage, who studied with Arnold Schoenberg, says 4'33 "is his most" important "work; his critics say this is a very bad joke.

The three-part worker instructed the players not to play a musical instrument throughout the duration of the compositions, to encourage the audience to get involved with the sounds of the voices at the concert hall.

Cage, heavily influenced by Zen Buddhism, first mentioned the idea of composing a completely silent work during lectures at Vassar University in the late 1940s.

Nevertheless, he estimates that this kind of song will be "incomprehensible to the Western context," and somewhat hesitant to write it down: "I do not want that song to appear as something easy to do or as a joke," he said at the time.

"I want to want it to be meaningful, and be able to live with it."

In 1951, he spent time in the soundproof room at Harvard University, and the experience he gained gave him the intellectual trust he needed to process his ideas.

"I heard two voices, one high and one low," he explained.

"When I exposed it to the workman on duty, he told me that a high voice is my nervous system at work, and the low is my blood is circulating."

Triumphantly, he added: "Until I die, the sound will always be there. And will continue to exist. No one needs to be afraid of the future of music. "

However, some assume that the future of music will never be threatened.

Since his first appearance, in Woodstock, New York, in 1952, the detractors have been annoyed, angry and upset by 4'33 ".

"They can not get the point," Cage said.

"There is no such thing as silence. What they think of silence, is because they do not know how to hear. You can hear the wind blowing outside at the first part. In the second part, the rain begins to knock on the roof, and in the third part the people themselves create all sorts of interesting sounds, as they speak or exit the room. "

But as stated by Julian Dodd in the recent TED Talk, the debate has remained turbulent.

Is it a musical piece? You decide.

Four Organs by Steve Reich (1970)

The audience of classical music concerts in New York is generally a fairly polite group, but not so on January 18, 1973.

Reich's music, written for four different types of Hammond and maracas organ, was written at the request of a visionary young conductor from the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Michael Tilson Thomas, who unhesitatingly incorporated him into the concert program alongside Mozart's number of Bartók and Liszt.

(The composer was in his time considered an architect in a musical revolution.)

But the reactions of the listeners that evening at Carnegie Hall ranged from "lighthearted", to one critic, to a threatening scream, to someone running down the stairs shouting "Okay, I confess!" As well as an old woman stomping -still his shoes on stage in an attempt to make the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Then we jumped into 2011, when Carnegie Hall held a great celebration of the 75th anniversary of "the greatest living American composer."

Your post was manually selected and voted for by @illuminati-inc (IINC) with support of @curie and its train of votes. About IINC: here. About Curie: here.