Every wonder how guitar and piano players seem to know how to play any chord? It may seem like lightning fast muscle memory, but it is more often a working knowledge of the musical patterns that go into making each chord. Creating these colorful vibrations is merely a counting game, and it isn’t very difficult to figure out. The following contains several ways to make and understand the musical language of harmony.

CHORDS

“… It’s all about getting from one note to the next, and those intervals and how you navigate your way through these vertical structures of chords. You realize that everything’s moving forward, and it’s all linear.”

David Sanborn

Spice up your melody, or just vibe. Chords make up the harmony of your song and have a direct connection with your jam’s mood and color.

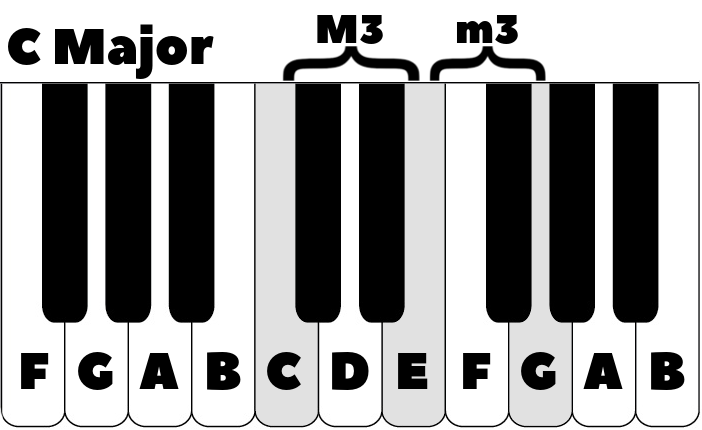

A chord is a collection of multiple notes played at the same time. Their names are dependent on the set of notes that make them up. There are thousands of different chords and an uncountable number of ways to play them. We’ll focus on the most common chords: in five minutes, you will know how to make every major and minor chord. First, let’s review our intervals. The only intervals we are concerned with at the moment are the major and minor thirds.

• A minor third is 3 half steps.

• A major third is 4 half steps.

Major Chords

All of our basic chords are built by stacking thirds on top of each other. Here’s how to make a major chord.

- Pick a note. This is our root.

- Find the note that is a major third above our root (4 half steps).

- Find the note that is a minor third above your new note (3 half steps).

- These three notes are your major chord. Your chord is named after the root you chose!

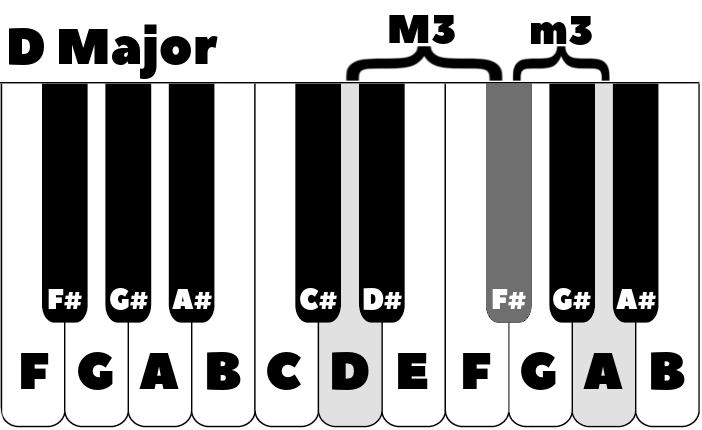

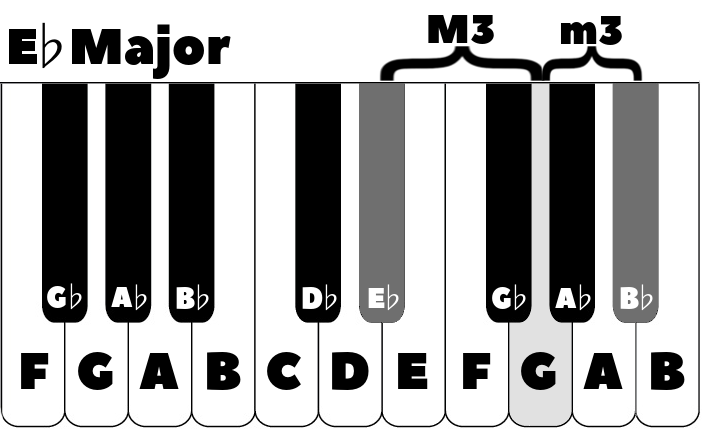

Here are some major chord examples. Try these out on a piano or piano app!

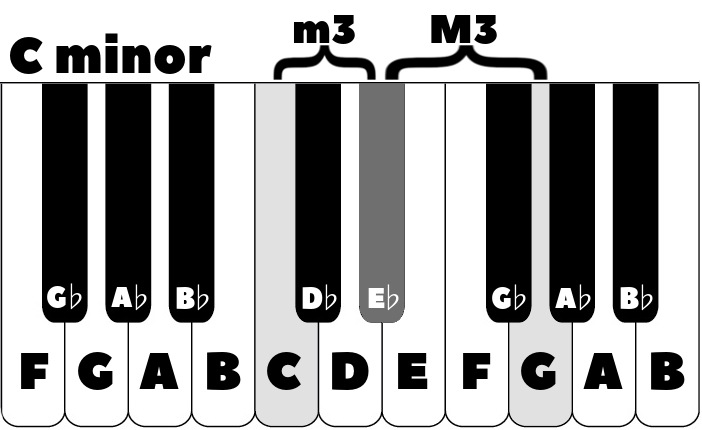

Minor Chords

You can now make all 12 major chords all over the piano. Be sure to practice this. Here’s how to make a minor chord.

- Pick a root.

- Find the note that a minor third above our root (3 half steps).

- Find the note that is a major third above your new note (4 half steps).

- These three notes are your minor chord.

Here’s a C minor chord. Notice how similar it is to a C major chord, differing only by one note.

This process is the same except we switch which kind of third comes first. Minor third first = minor chord; major third first = major chord. Remember that these types of chords require a major third and a minor third to sound normal! When musical patterns become perfectly symmetrical, they tend to sound unnatural.

Augmented and Diminished Chords

Try this out: Make a chord that is built with two major thirds using the method above. What does it sound like? This is called an augmented chord. This one doesn’t exist naturally in our tonal system. Two minor thirds stacked together make a diminished chord. Both of these sound strange, but composers and musicians still make use of them because of their specific sound. Knowing how to make major, minor, augmented, and diminished chords means you now have access to a whopping 48 different chords! These are not the only chords that exist, but most of the others begin with these as a base and add more notes on top.

TIP: A good goal is to eventually have all of the major and minor chords memorized. Knowing how to make them is the first step but won’t save you if you’re in a pinch. Start by saying or thinking the notes in a chord after you make each one. Eventually they’ll begin to stick.

LANGUAGE TIP: Lingually, a 3rd is two letter names away. This results in the D major chord from earlier containing an F# (D-E-F) instead of a G♭ (D-E-F-G). A C minor chord contains an E♭ (C-D-E) instead of a D# (C-D).

Diatonic Chords

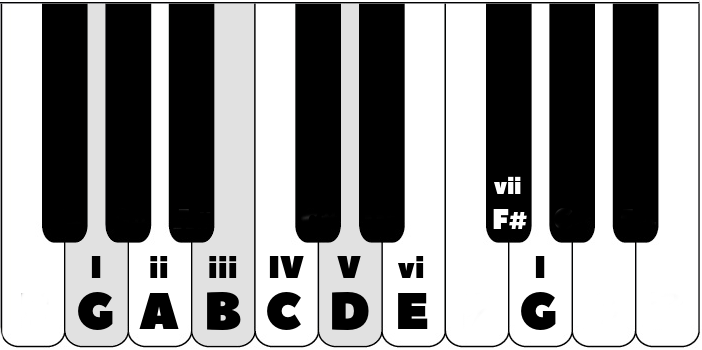

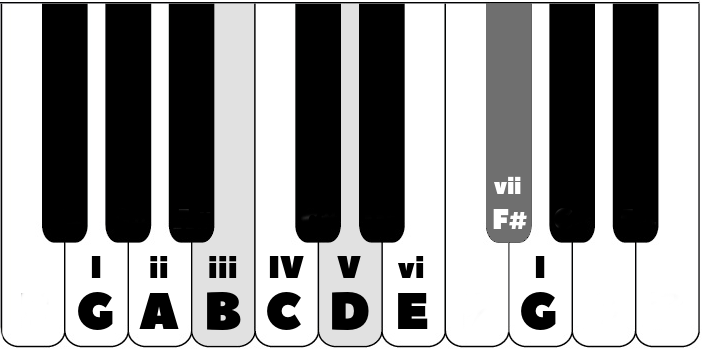

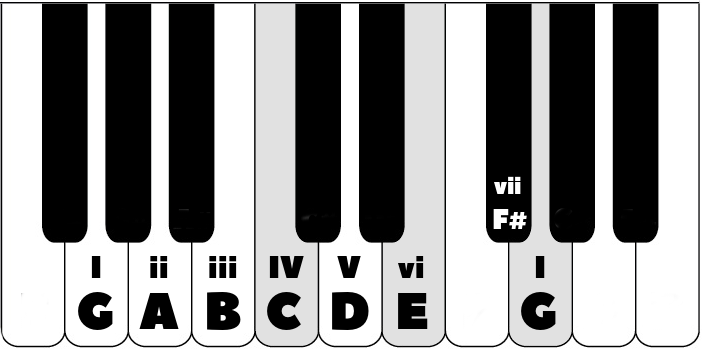

Things are simpler when we are working within a key (see Chapter 5: The Circle of Fifths). A key has 7 notes to choose from, so it also has 7 chords to choose from. These are called diatonic chords, and they help us maneuver within a key, figure out songs by ear, and conduct some musical detective work. Let’s use the key of G as an example.

First, musicians number the notes of each scale, the root of the key being I (Roman numerals are used for this). Unlike the previous method of making chords (counting major and minor thirds), this method is more about finding the chords that already exist within a key and naming them. A third can be found by skipping one note, so let’s stack some thirds.

When we assemble thirds starting on G, we get a G major chord. We know it’s major because the distance between G and B is a major third (4 half steps), and the distance between B and D is a minor third (3 half steps). We can use our previous method of making chords to figure out what a chord is. We call this the I chord (one chord) because it is the chord built on the I. Here are the other chords in this key. Don’t rush! Understanding these principles is an enormous time-saver. Here are a couple of other examples, the iii chord and the IV chord.

• I chord - major

• ii chord - minor

• iii chord - minor

• IV chord - major

• V chord - major

• vi chord - minor

• vii chord - diminished

NUMERAL TIP: Notice that our Roman numerals are uppercase and lowercase depending on whether they are major or minor.

• I, IV, V are major.

• ii, iii, and vi are minor.

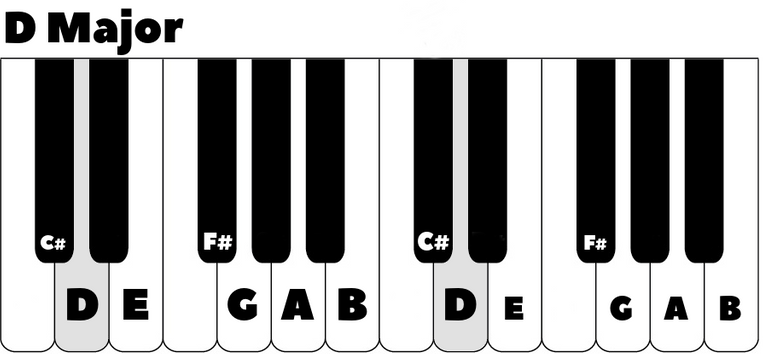

Let’s apply this to a couple of other keys. Here’s the next key in the circle of fifths, D major.

• I chord - D major

• ii chord - E minor

• iii chord - F# minor

• IV chord - G major

• V chord - A major

• vi chord - B minor

• vii chord - C# diminished

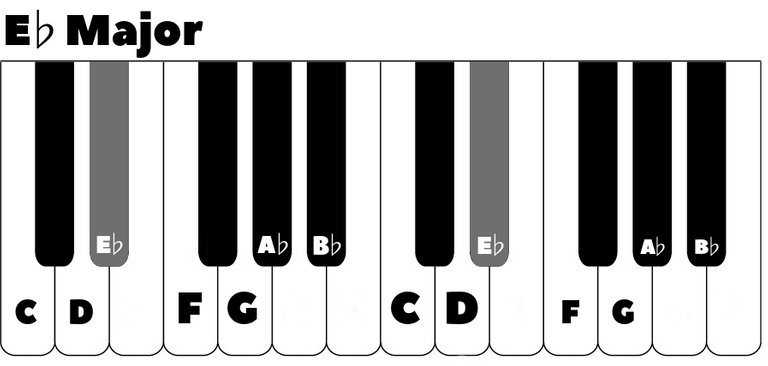

Here’s a completely unrelated key, Eb major.

• I chord - Eb major

• ii chord - F minor

• iii chord - G minor

• IV chord - Ab major

• V chord - Bb major

• vi chord - C minor

• vii chord - D diminished

You can use this to figure out what key a song is in if you know the chords. For example, consider a song that moves back and forth between the chords D minor and E minor. There’s only one condition in which there are two minor chords right next to each other: the ii and the iii. That means D is ii, E is iii, and I must be C. We are in the key of C major.

If a group is jamming on the chords F major and G major, those chords must be IV and V, the only condition in which there are two major chords right next to each other. If that’s true, then I is C, and we are in the key of C major again.

CHALLENGE: A band is playing around with the chords E minor, A major, and B minor. What key are they in?

NOTE: Though this method covers a huge percentage of songs and ideas, remember that not all songs stay in one key the whole time. Also, the band in the previous challenge are playing in the key of D.

Inversions

These methods are good ways of building, finding, and identifying chords. However, all of the chords we’ve checked out up to this point are in root position, meaning the root is on the bottom. A C major chord is not just C-E-G; it is any combination of C’s, E’s, and G’s all put together. It doesn’t matter in what order the notes happen or how many different octaves of the same note there are. The different ways of playing a chord are called voicings, and the voicings you choose play an important role in how chords sound.

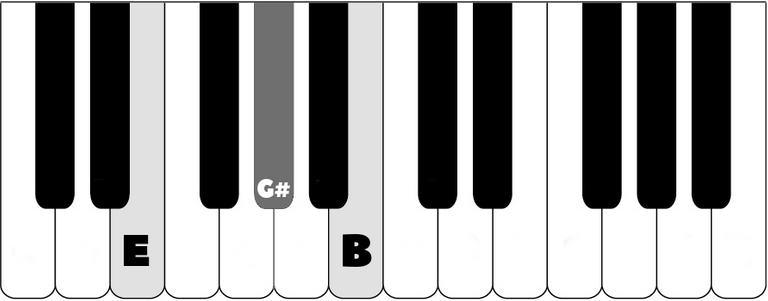

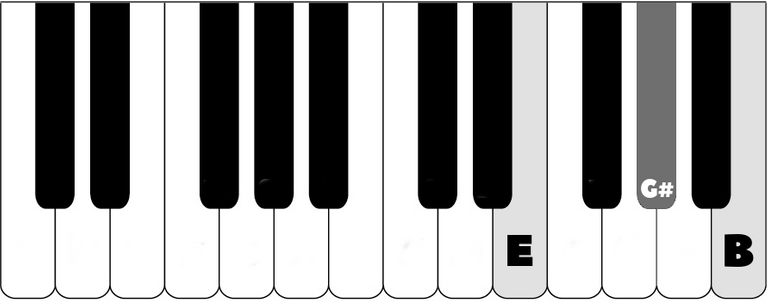

Root position is one of three inversions. Here’s E major in root position.

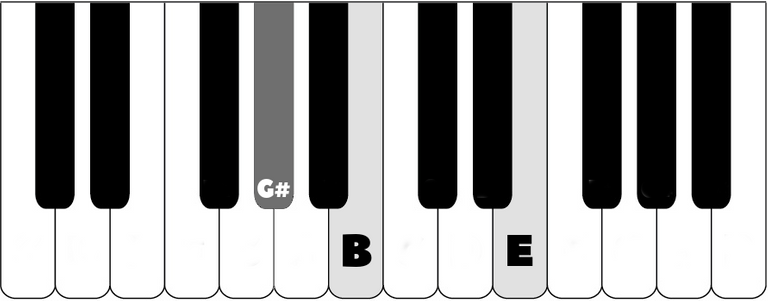

If we swap out the E for a higher E, we still have an E major chord, but the notes are ordered differently. Notice the distance between B and E; that’s not a third! It is a fourth. Inverting your chords gives you a fourth to keep track of. This is called 1st inversion.

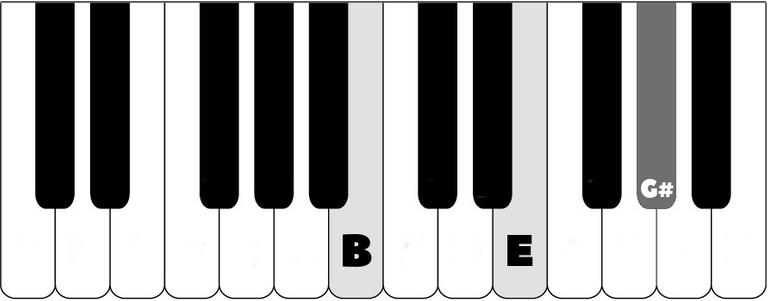

Let’s swap the G# for a G# one octave higher. Now we have a fourth on the bottom of our chord instead of the top. This is called 2nd inversion.

Replacing the B with a B one octave higher gets us back to root position because E is on the bottom again. There are only three inversions because there are only three notes in this chord (chords with more notes have more inversions). In this way, you can can walk chords up or down until they sound the way you want them to.

NINJA CHORD TIP: If you can’t figure out what a chord is, check to see if it’s inverted. If you have a fourth, it’s an inversion. If you rearrange the notes until you only have thirds, then your lowest note is the root.

There it is; the key to making every single basic chord on every instrument that plays with our standardized musical language. If you keep stacking thirds on top of each other, you can get other types of chords with different kinds of sound colors. We’ll save these for another chapter! Have any questions? Drop them here!

You had some huge success in some of your earlier music blogs. Exciting huh? Do you play music? I'm a dabbler in guitar, piano, and was actually a French Horn major at UCLA. So cool posts dude.Follwed

I play and teach music full time! You must've played a lot of orchestral music. Favorite pieces?

Nice post.. Upvoted and followed

Follow back @gauravchugh Thanks