You can compose a song made of just one chord repeated according to a certain pattern; but usually you use several chords, and of course a chord comes after another (except the first chord), and there will be another chord after it (except for the last chord). We have a chord progression. The already mentioned cadences are, of course, chord progressions.

Common notes in sequences of two chords

When we put a chord after another we can have different situations: the chords don't share any note, the chords share a note, the chords share two notes, and so on. If we are using triads, sharing three notes mean we have the same chord.

Triads with the root notes which are one step far (I-II) or six steps far (I-VII), share no notes.

Triads with the root notes which are two steps far (I-III) or five steps far (I-VI), share two notes.

Triads with the root notes which are three steps far (I-IV) or four steps far (I-V), share one note.

Voices or parts

A chord is made of several notes, and each of these notes can be sung by a different human voice or (monophonic) instrument. Instead of thinking of a chord like a “vertical unit”, we can see it as a result of overlapping voices or parts which evolve horizontally, i.e. overlapping melodic lines (though the name “melody” refers conventionally to the upper voice).

So, when we put chords one after another, we must imagine as if each note of a chord belongs to its own melody, each sung by some elements of a choir or ensemble of instruments. From the point of view of the singer or player, his/her “melody” has steps and jumps which can be easier or harder to play or sing.

When a part is assigned to a specific instrument, we must check that the instrument can actually play it, because instruments have ranges — lower and higher playable pitch — and also there are intervals that could be hard to be played, especially fast (we hardly will meet these limits).

Each part should be cantabile (singable), and this is usually achieved avoiding to have big jumps and too many jumps in general. The general rules is that the upper parts (all but the bass or lowest part) shouldn't jump more than a major third (M3), but other manuals say it's not mor than a perfect fourth (P4).

In the exercises we use four parts or voices, two per staff — it's a four-parts harmony. This allows for triads (we'll double a note) and seventh full chords, while for chords of more than 4 notes we'll need to omit one or more notes (we'll do that also for seventh and in cases when doubling or omitting gives a better parts' motion).

The upper voice can be called soprano (and it's the melody), the middle upper voice can be called alto, the middle lower voice can be called tenor and the lower voice can be called bass. If we want that our four-parts harmony is sung by an actual choir, we need to consider the real ranges of human voices.

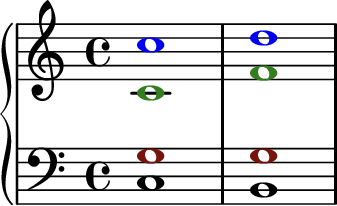

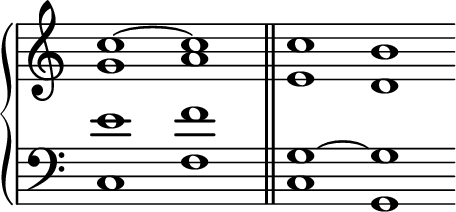

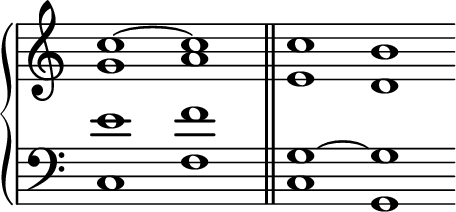

In this example we have the soprano which steps up from C to D; the alto which jumps from C to F; the tenor which doesn't move; the bass which steps down from C to B.

The colors won't be needed since each voice can be easily recognized by its position: the lower notes will be always the bass, the higher notes will be always the soprano, the second lower voice will be always the tenor and the second higher voice will be always the alto.

Indeed there are situations when voices could cross. But we won't do it.

Motions

If we consider two voices and we see how they move one with respect to the other, we can have four kind of motions.

The parallel motion is when two voices move in the same direction by the same interval.

The similar motion is when two voices move in the same direction, but not by the same interval.

The contrary motion is when two voices move in the opposite direction, one upward and the other downward, or viceversa.

The oblique motion is when one voice stays still while the other moves.

Harmonic and melodic connections between chords

When we have two chords, they can have notes in common, as seen above.

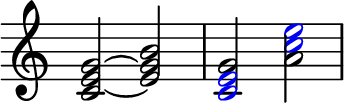

We talk of harmonic connection when the common note stays in the same voice. In the following examples C (first pair) and G (second pair) are kept in the voice where they first played.

Considering I-IV and I-V (one note shared):

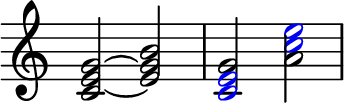

We talk of melodic connection when each note moves.

In the first bar, instead of staying on C, the soprano jumps down to A; the C (at a different octave, of course) is then played by the tenor which jumps from E down to the aforementioned C. In the second bar, the tenor jumps from G to B instead of staying on G, and a G is then played by the alto, reached by another jump (from E to G).

Chords which don't share any sound can be connected only melodically, of course.

Taboo section

Here a few rules you can find in a classical manual of harmony.

- Two perfect chord can't come one after another in the same melodic position.

This is because parallel fifths, octaves (and unisons) are prohibited, and keeping the same melodic position would give them.

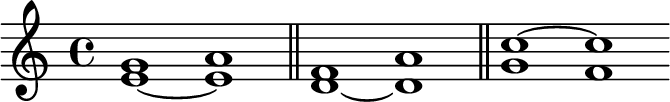

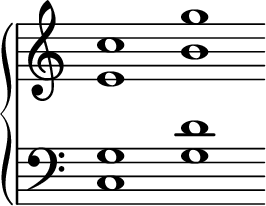

In bass and soprano voices we have C3-C5 (octave) moving to G3-G5; and also, in bass and tenor voices, C3-G3 moving to G3-D4 (fifth).

Also the unisons is prohibited as the octaves (though the similarity is the other way around, I suppose). The prohibition holds also if the jump isn't in the same direction and if the interval is compound (a fifth and and octave must be reduced to just a fifth).

Thus the following aren't considered good for a student:

Notice that also the succession 1-8 (unison followed by octave) is treated as 8-8 (octave followed by octave).

Now you might think that this rule is absurd, because parallel octaves are all around in orchestral scores, and unisons too! Though, they are used mainly to enrich the timbric texture, not as harmonic device — also because being strictly consonant intervals, they don't create a very complex and full harmony.

There are also hidden fifth and octaves. It happens when two voices jump so that their arrival notes form now a fifth or octave (which they didn't on their starting note), but also they preceding notes form the same interval.

In this example E-C isn't an octave, but G4-G5 is. So we need to check: E jumps to G, and the note preceding the landing note is F. The upper voice jumps from C to G, and the note preceding the landing note is F again. So we have F4-F5, i.e. a hidden octave.

Another strict (for students) rule:

- A voice can't move by an augmented second interval.

We've seen that the augmented second doesn't exist in major and natural minor scales, so it won't be so hard to comply, unless you use harmonic minor scale or you are modulating.

Harmonizing a melody

Ok, so we can put chords one after another and by definition of common words we have a sequence of chords.

Three chords are enough to “cover” all the seven notes of a diatonic scale. For example I, IV and V — we've seen that these are important chords.

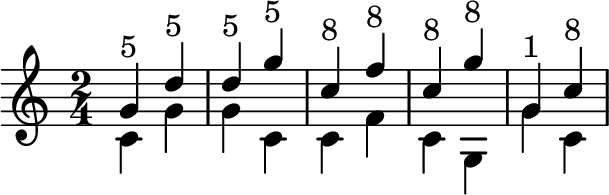

A melody can be harmonized using only these three chords (though in future we would like to use more tricks). We need just to follow few rules (and don't forget the taboos and how two chords can be connected):

- Let the first chord be I of the tonality; the note of the melody will be one of note of this chord, likely the root. This will be also the last chord.

- When in the melody there's a jump greater than a third, keep the same chord given in the downbeat, but change its melodic position.

- When in the melody there's a repeating note, you will use a different chord, or change the position of the chord you've just used.

- Do not use on a downbeat the same chord used for the upbeat; said otherwise, change chord on downbeat.

- Do not make the bass jump by a fourth or fifth in the same direction.

- The IV must always come before V, but not after. So you will use I-IV, I-V, IV-V, V-I, IV-I but not V-IV (except in the case of a semicadence, when a V is a sort of “suspension point”, and the “resumption” can begin with a IV)

- When the melody jumps by a fourth or a fifth, you can use two different chords (I/IV for the first note, I/V for the second)

- if you use the root position for the first note, on the second note you will use the first inversion of the other degree, and viceversa; e.g. I 6V, or 6IV I, and so on.

With these initial basic rules, you should start to harmonize a melody in a simple way, without too many mistakes.

In the next lesson (which could be named as Lesson 8, part 2, but I will call it Lesson 9 anyway) we'll try to apply these rules to a melody.

Index of the lessons so far (the current one included)

- Lesson 1: basic knowledge about sound.

- Lesson 2: dissonance, consonance, tuning, 12-tones equal temperament, notes' names and notes on a staff, treble and bass clefs.

- Lesson 3: semitones, duration, beaming, tempo.

- Lesson 4: time signature, downbeat, upbeat, rests, ascending major and natural minor diatonic scales, key signature, circle of fifths.

- Lesson 5: scale degrees, more scales, intervals.

- Lesson 6: intervals, harmony, triads, tonality, diatonic modes, Gregorian modes.

- Lesson 7: harmony, consonance, dissonance, analysis, inversions, voicing, figured bass

- Lesson 8: connecting chords, chord progressions; parallel, similar, contrary and oblique motions.

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.