Shooting spaceships. Stunning lasers. Blazing blasts. These are things that a war in space would more likely than not include.

As far back as Star Wars, people in general has been intrigued by the visuals of room struggle — it's cutting edge, exciting, and grandiose fights are dispossessed of the gut that so regularly goes with earthbound clash. Also, as far back as Sputnik, people have been placing things into space, bits of innovation that are presently key gear-teeth in the apparatus of society. We depend on satellites for everything from charge card exchanges to mapping applications. The military needs satellites for correspondence, and in addition for the imaging that gives them a chance to watch out for companion and adversary alike.

Thusly, disregard the Death Star, this amalgamation of squinting equipment drifting in Earth's circle would be target numero uno. However, would it be shrewd to pull the trigger?

It's A Trap

Here's the short answer: Orbital firecrackers are not liable to start at any point in the near future.

"Everyone accept that in the event that we get some person that shoots at me in space, we will shoot back in space. Indeed, that is a loathsome thought," says Colonel Shawn Fairhurst, the delegate chief of Strategic Plans, Programs, Requirements and Analysis at the Air Force Space Command.

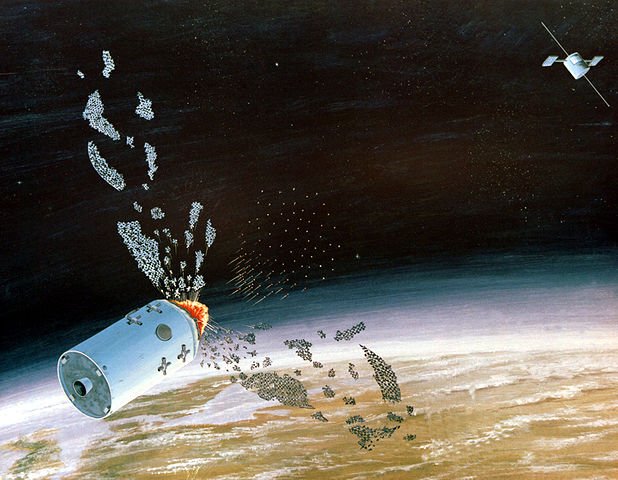

"When you explode something on the ground, it falls back to the ground. In the event that you explode something noticeable all around, the plane returns to the ground," he says. "The issue is, the point at which you explode something in space, it makes flotsam and jetsam that never descends."

We have little capacity to control or safeguard against that flotsam and jetsam, which implies the potential for inadvertent blow-back is high. It doesn't take much to shred metal when something is moving at 17,000 miles for every hour, as articles in low Earth circle may be. A paint chip assessed to be the extent of a grain of sand left a quarter-inch pit in a space carry window, and the sheets should once in a while be supplanted on account of comparable effects. Something the extent of a marble could be destroying to a satellite.

At the point when the Chinese crushed one of their own satellites with a rocket in 2007, it made a billow of trash, each piece with the possibility to decimate satellites and challenged person correspondence and money related systems. Regardless of whether an assault were focused at one country's satellites, the aftermath would be a move of the dice—best to keep away from the matter of exploding things in space inside and out.

"Our entire objective isn't to have a war in space. A war in space isn't useful for anyone," Fairhurst says. "On the off chance that you begin pulverizing GPS satellites, you begin taking ceaselessly timing from organizations, the GPS on your Google will stop working. That is bad for anyone, that is a worldwide issue that can have implications over a worldwide economy rapidly."

The Air Force essentially considers the dangers required with crushing something in circle to be too high, as indicated by Fairhurst. He says they're concentrating on making their satellites more flexibility and excess, which makes them less lucrative targets. The other need is to keep a foe from consistently propelling a rocket toward a satellite in the principal place."Instead of building goliath satellites that are sitting ducks … would we be able to take a gander at breaking those things into littler pieces so on the off chance that you lose some portion of it whatever is left of the capacities still go on?" he says. "In the event that they see a danger, would they be able to move off the beaten path?"

Other potential, less confused, satellite assaults incorporate hacking, sticking a flag or blinding its sensors with lasers. Essentially prodding a satellite out of circle could be sufficient to upset it briefly too. Every single offer mean of undermining the military's capacities, and the Air Force stresses that such strategies could assume a part in future clashes, Fairhurst says. While he focuses on that a physical assault isn't their objective, he says the Air Force is set up to safeguard its benefits.

We Come In Peace

"There's this thought associated with space that it ought to be utilized for quiet purposes," says P.J. Blount, a postdoctoral specialist at the University of Luxembourg and the manager in-head of the Journal of Space Law. "Also, that thought stretches out an increased status to space for states not to take part in these kinds of exercises."

That serene assignment for space depends on the 1967 "Bargain on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies," also called the pithier "Space Treaty." It's controlled by the United Nations, and it states, in addition to other things, that space is for quiet uses just, and denies setting weapons of mass devastation in circle. It additionally denies weapons of any kind on the moon. Up until this point, the bargain has been maintained, in extensive part.

It doesn't keep the utilization of room for military exercises, so things like covert operative satellites and so forth are permitted, and it's been by and large acknowledged that protective tasks are permitted too, Blount says. The bargain doesn't set down immovable principles either — it's not clear what might happen should anybody damage it.

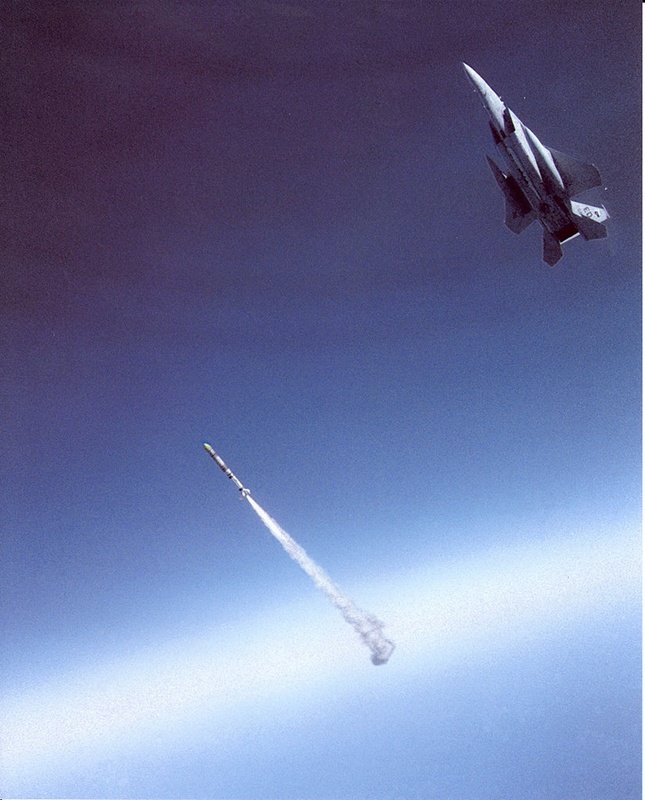

Countries have pushed at the edges of the arrangement before. In 1985, a U.S. F-15 warrior stream propelled an extraordinarily outlined rocket into space to take out a maturing Department of Defense satellite more than 300 miles over the Earth — China accomplished something comparable in 2007. The U.S. test partook against the scenery of the Cold War, and Russia correspondingly considered a framework intended to take out satellites with a touchy shuttle.

Be that as it may, for all the acting and the potential focal points of decimating each other's satellite systems, it never happened.

"The United States and the USSR were enemies and they cooperated to guarantee that contention did not emit in space," Blount says.

Questionable Future

Today, the scene has changed. Circles around the Earth are becoming more busy. Littler nations like Iran and North Korea have progressed toward becoming players in the space race, and there are stresses that they may not waver to bring war to space. North Korea, particularly, does not depend on satellite systems a similar way that we do, so they have far less to lose by taking them out.

What's more, the adjust of upsides and downsides could change considerably more as we additionally grow the scope of our exercises in space. Settlements in circle or on another planet, and in addition mining tasks in space, carry with them two of the most powerful elements for war — domain and assets.

Making laws that characterize appropriate from wrong in space would reduce future issues, yet the three space superpowers — the U.S., Russia and China — appear to be reluctant to place any in the books. In spite of the fact that Russia and China have been pushing a settlement forbidding weapons in circle or on divine bodies, Blount says it's more advertising act than fair exertion. They know the settlement has minimal possibility of being endorsed, he says, allowing them to keep creating space capacities while seeming to work towards peace.

The U.S. has adopted much a similar strategy. President Bush declined to arrange any settlements, as indicated by Blount, and endeavors under president Obama didn't go anyplace. In the mean time, Congress as of late upheld for a "Space Corps" inside the Air Force — however the military branch did not bolster it — committed to safeguarding U.S, interests in space. The Air Force sees its space spending increment by eight percent under the Trump organization's most recent spending proposition. The cash is to a great extent reserved for innovative work and incorporates more finances for a rocket cautioning framework and space powers.

"I think each of the three of these states see the uncertainty in the principles as more gainful to them than definitions as of now," Blount says. "You see a considerable measure of discuss needing to de-weaponize space, yet don't see a great deal of development in characterizing the standards."

The final product is a proceeded with push by each of the three countries toward military readiness in space. It's valid that a space war may be something nobody needs.

{ #Note :- Picture Source : All Picture Is collected From Internet.

&

Reference Link :