In January 2009, Eastern Europeans were rudely reminded of a very blunt fact: If Russia wants to shut off the gas, it can.

Angered by backlogged debts, Gazprom, Russia's massive state petroleum and natural gas corporation, cut off its supply of gas to neighboring Ukraine – and, through it, to parts of the European Union. For weeks in the dead of winter, millions of Europeans were stranded without power, as Gazprom and its Ukrainian counterpart Naftogaz blamed one another for the crisis. While the flow of gas eventually resumed, European governments emerged from the experience shaken, and for good reason.

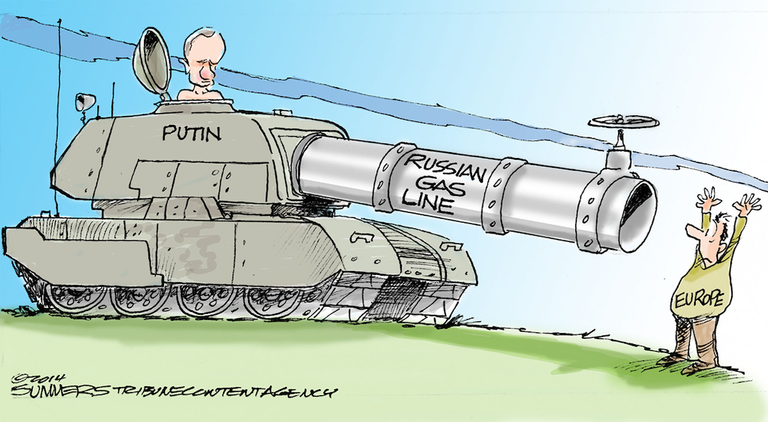

Russian President Vladimir Putin has turned natural gas exports into a weapon, a leash designed to keep Russia's neighbors from straying too far westward. Today, we are again reminded of the Kremlin's grip on European energy by the planned expansion of the Nord Stream pipeline, which is scheduled to double its capacity by 2019. Polish and Baltic leaders are painfully aware of their dependence on Gazprom and are desperately looking for alternative suppliers. Fortunately, the United States now has the ability to fill that role. America's first overseas shipment of liquefied natural gas left Louisiana's Sabine Pass liquefaction terminal in early 2016, and Eastern Europe has already opened its ports to the export. Poland received its first LNG shipment from the United States in early June, when it arrived in that country's new regasification terminal at Swinoujscie. Later the same month, Lithuania signed a contract with American LNG supplier Cheniere, and the first shipment from that arrangement is due to arrive to a terminal at Klaipėda in August.

This is a good start, but America's LNG shipping industry is still in its infancy. There are currently only two operational LNG terminals in the continental United States, and – although three more are under construction – America is still simply not producing enough volume to be competitive with industry leaders Australia and Qatar.

That, however, could change with a little help from Congress. American lawmakers have the power to include funds to increase LNG production and export capability in the upcoming infrastructure bill soon to be debated on the Hill. If they did, the money could be used to build more export terminals on our coasts, expand and renovate existing refineries and improve storage facilities to hold the LNG produced by them. Research into streamlining costs during liquefaction, refrigeration and shipping is also sorely needed, and well within Congress's capacity to empower. The goal should be to build a sustainable American "surge capacity" in the natural gas field. Can American LNG fully replace Russian supplies to Eastern Europe? The answer, at least for the foreseeable future, is "no." But it doesn't need to. While Russia's enduring goal is to maintain a near-monopoly over that region's energy supply, the U.S. has no need to match Gazprom's volume. It only needs to provide enough LNG to make sure Eastern Europe has a replacement stream if Gazprom or its controllers in the Kremlin decide to replay the events of 2009.

This is as much a security argument as it is an economic one. Simply put, NATO states that currently rely on Russia's pipelines see American LNG as a potential form of self-defense, and are likely to be willing to pay handsomely for it.

When President Donald Trump spoke to the people of Poland in Warsaw earlier this summer, he declared that the United States is "committed to securing your access to alternate sources of energy, so Poland and its neighbors are never again held hostage to a single supplier of energy." LNG is one of the keys to honoring this promise. The United States cannot defend NATO's most vulnerable members with troops alone. We need to make sure that Eastern Europe has an energy back-up plan.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://www.usnews.com/opinion/world-report/articles/2017-08-10/how-the-us-can-fight-russias-weaponizing-energy

meep