In so many interviews I had with the wise women of the Amazon or with women who wanted to talk to me about their experience in pregnancy and childbirth, I was able to verify that the Amazonian peoples possess an extraordinary wisdom regarding techniques, care and conceptions about the physiology of women, childbirth and perinatal care, and if there is one thing certain, it is that the peoples of the Venezuelan Amazon do not share the vision of the majority of Western women about childbirth as a torment, an unavoidable but painful process. In fact, women in their villages can give birth unaccompanied and the most frequent thing is to give birth during a labor that continues immediately after the baby has naturally come out through the vagina.

In Europe before the 18th century, childbirth and prenatal care were left in the hands of midwives, women who provided assistance by various means and who had learned their knowledge from other women orally. But in the second half of that century, gynaecological medical knowledge is instituted in France, births and everything related to them become the prerogative of male doctors (because only men could go to a university to obtain a degree); then an unnatural, inconvenient and unused position is prescribed for the ejection of the baby: the supine decubitus. With this transfer and gradual disincentive of the profession of midwives, woman's body is medicalised: the natural fact of childbirth is assimilated, by being treated by a doctor, to an sickness.

The West has pathologized the processes of the human female's anatomy: menstruation is an uncomfortable trance that should be relieved by drugs, pregnancy is a medical condition and childbirth requires surgical interventions. But this bias is actually a tradition in the Western world. For Aristotle, women's bodies were gaunt and without vital energy; fatuous and sickly except when he carried a man's offspring in his belly. In Freud's The Interpretation of Dreams we may find that girls experience the complex of being castrated males, that is, their body is defined by something that is missing. In another of his works, Studies on Hysteria, he proposes that the origin of this neurosis, an exclusive suffering of women, is the lack of sex.

In the Casa de Atención para las Mujeres Indígenas Amazónicas -Care Home for Amazonian Indigenous Women- (CAMIA, from its Spanish acronym), which we have already been able to talk about in a previous post on my blog, we seek to offer a traditional indigenous midwifery service. Our purpose is that the indigenous midwives can be in charge of the prenatal and postnatal control of the patients, or what is the same, that they are the ones who provide treatment to the discomfort of pregnancy, complications of childbirth and the puerperium at the same time that we conserve and promote the local knowledge in an urban context, in which by western influence and by the contempt to the medicine and the indigenous pharmacopoeia, these tend to be forgotten.

Prenatal checkups may be essential to prevent complications during childbirth. Data from the ECLAC/CELADE report Maternal and Child Health of Indigenous and Afro-descendant Peoples of Latin America (2010) shows that the majority of indigenous women did not attend gynaecological prenatal check-ups on more than one occasion, which seems regrettable, but at the same time a magnificent opportunity to propose control by traditional midwives as an alternative. The fact that indigenous people are the segment of the population with the highest rate of deaths at birth in most countries in the region also demonstrates that midwifery knowledge has been abandoned; in the situation of scarcity of health professionals and supplies in Venezuela, indigenous traditional midwifery is more a necessity than a choice, one that can save more than one life in the midst of the deadly vortex of the crisis.

In the Venezuelan Amazon there are twenty recognized indigenous ethnic groups, three of which have their ancestral territory in Ecuador and southern points of Colombia relatively far from the Venezuelan border. Each culture has its own methods for determining, for example, the sex of the fetus, for treating certain anomalies or discomforts related to pregnancy, and ideal positions for childbirth. The extraordinary biodiversity of the Amazon basin also allows for considerable variation in the plants used in the pharmacopoeia of each village.

Our service seeks integration among the Western allopathic care system and indigenous health systems. The latter are holistic, that is, they treat brokenness or illness in an integral manner, never disassociated from the behavior of the affected person nor from his or her relationship with the community which he or she is a member of. They are less invasive and can offer answers that Western science does not have yet. However, there are problems these systems cannot solve (for example, sometimes there is no other way to save a baby's life than by means of a caesarean), so optimal attention to the greatest number of emergencies can only be achieved when they are conceived and used as complementary systems.

Finally, the task at home for researchers such as myself is to gather the health statistics up that has ceased to be published or even stopped to be considered useful after the establishment in Venezuela of 'zones of silence' as a State policy: these 'zones of silence' are vast areas of the most remote regions, which are often of a significant indigenous population, over which the alteration of causes of death and epidemiological records are let and ordered.

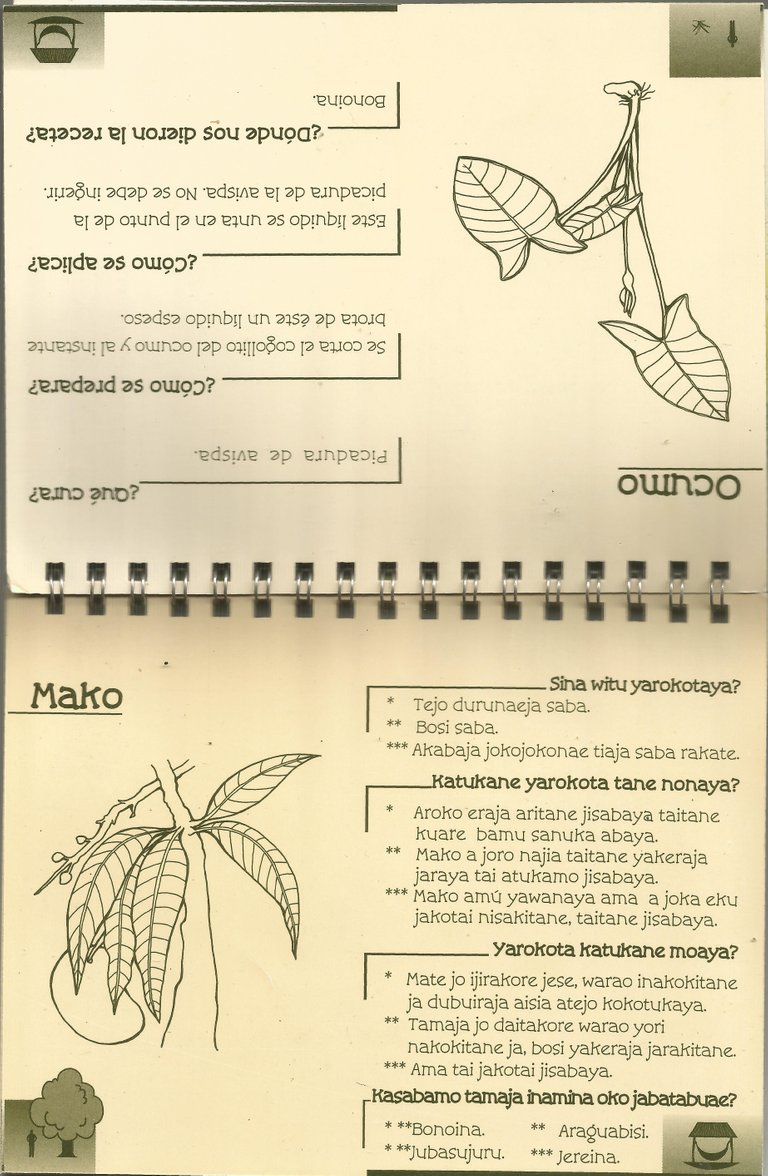

One of my assingments is the compilation and arrangement of the uses of medicinal plants, so that in the near future the care home may have a small garden for the use of midwives and house assistants. Our intention is not to collect this information in order to preserve it in the privacy and comfort of the cloisters of scientific knowledge, but to publish pamphlets and short informative books for consultation by the indigenous people whom this knowledge belongs to by cultural attachment and thus contribute to cultural vitality and continuity, even if we have to face the disinterest of young people to learn the wisdom of their grandparents.

Hi ngetal, @hobo.media upvoted you for $0.01 and resteemed your post. If you want future random upvotes/resteems just follow.

Peace, Abundance, and Liberty Network (PALnet) Discord Channel. It's a completely public and open space to all members of the Steemit community who voluntarily choose to be there.Congratulations! This post has been upvoted from the communal account, @minnowsupport, by ngetal from the Minnow Support Project. It's a witness project run by aggroed, ausbitbank, teamsteem, someguy123, neoxian, followbtcnews, and netuoso. The goal is to help Steemit grow by supporting Minnows. Please find us at the

If you would like to delegate to the Minnow Support Project you can do so by clicking on the following links: 50SP, 100SP, 250SP, 500SP, 1000SP, 5000SP.

Be sure to leave at least 50SP undelegated on your account.

woah, so many amazing and interesting facts all in one post here

I think, as a woman, giving birth, and having a child, is one of the most magical and spiritual things we will ever do.

Congratulations @ngetal! You have completed the following achievement on the Steem blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click here to view your Board of Honor

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPTo support your work, I also upvoted your post!

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard: