City Attorneys Liberally Apply Legal Privileges to Stop Release of Emails in Court

Though there’s been a lull in the public fight over a proposal to build the Los Angeles Clippers a home arena in Inglewood, California, lawsuits challenging the process have proceeded through December and now into January.

One community group, Inglewood Residents Against Takings and Evictions (IRATE), filed suit in July against the City of Inglewood and Murphy’s Bowl, LLC – the company representing the Clippers. The complaint alleges the city failed to properly follow California’s preeminent environmental law, the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), in negotiations over the arena.

Among other claims, the suit alleges Inglewood made development “pre-commitments” without public input, constituting a violation of CEQA. The city claims they haven’t committed to anything, as the city council has merely signed onto a June 15th “Exclusive Negotiating Agreement” (ENA) with the purpose of hashing out plans for the arena. But several details are certainly established, such as where to site the project, how much city-owned land will be utilized, and whether businesses and residences might be subject to eminent domain to make way for the arena.

So has the city made development pre-commitments to Murphy’s Bowl, LLC or not?

To help answer this question, IRATE’s attorneys sought any documents and communications relating to the ENA or the arena proposal dating back to September of 2016, nine months before the ENA’s rather sudden announcement in June. In fact, CEQA itself requires the administrative record of any major development be published as a way of forcing transparency in public-private development partnerships.

The city responded on December 14, 2017 with two signed declarations by city attorneys, the contents of which were less than enlightening. Just a few non-public documents made their way into the declarations: some emails from the Deputy City Manager Yakema Decatur regarding meeting agendas; an exchange between Mayor James Butts and a local reporter; and a fan email to Mayor Butts from an Inglewood resident.

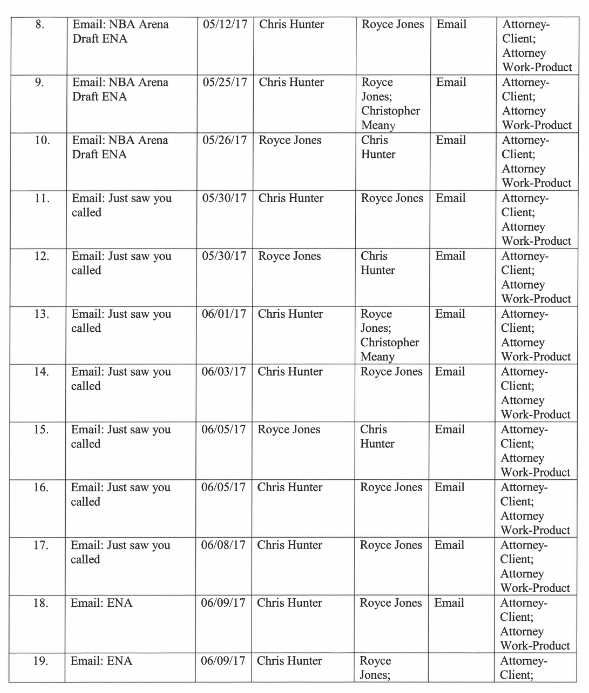

But of course, the ENA didn’t appear out of thin air on June 15th. Surely there were numerous communications between Inglewood and Murphy’s Bowl prior to the approval of the ENA. And the city admits that written communications prior to June 15th do exist – they just can’t be released, due to attorney-client privilege and something called attorney work-product privilege.

It’s a stretch to attempt using these privileges to protect over 130 emails between the city’s hired law firm, Murphy’s Bowl, and the Clippers’ representatives. Both privileges are extremely narrow in scope and are even more limited in CEQA suits according to California case law.

Are these privileges applicable in the context of this case?

Let’s start with attorney-client privilege, a protection for communications in which an attorney gives legal advice to a client. This privilege is meant to ensure open communication between a lawyer and whomever the represent, as well as preserving the integrity of the legal system. For example, it stops a prosecutor from serving a subpoena to the very attorney defending an alleged criminal. But according to the American Bar Association, “a client can never protect facts simply by incorporating them into a communication with an attorney.” That means an individual or entity can’t hide evidence of malfeasance or noncompliance with the law simply by sending that evidence to their attorney. From the ABA, “communications will only be privileged if the party sought, and the attorney rendered, legal advice.”

Furthermore, any communications that involve “third parties” (that is, anyone other than the attorney, the client, or their subordinates) are not privileged unless the third party shares a “common interest” with the attorney and client. Unfortunately for the city, California case law has blown a hole in that doctrine when it comes to CEQA lawsuits.

In 2013, the Superior Court of Stanislaus County rendered a decision that determined any communication between developer and city that might be privileged through comment interest is not, until a development has been approved. Prior to approval, the interests of city and developer are fundamentally different, because they both want what’s best for them.

Given this ruling, the only way the city can succeed in privileging these communications is to admit development was already approved – but that contradicts the cornerstone of their legal argument, that the ENA is merely to facilitate discussion.

Inglewood also invokes attorney work-product privilege, which applies to anything created by an attorney in preparation for a lawsuit. Essentially, it stops one side of a lawsuit from compelling the other side to release documents that may reveal their legal strategy.

But the city is attempting to claim this privilege for an outlandishly broad set of communications. Take a June 14th with the subject “Wiring Instructions, ” presumably containing instructions on how Murphy’s Bowl, LLC should send the city the $1.5 million deposit it owed as part of the ENA. Unless that message contains information specifically written in preparation for a lawsuit, it is not attorney work-product. To claim that it is, the city would necessarily be implying they were expecting to be sued well before the ENA was even made public.

What happens next?

IRATE’s lawyers filed a motion on January 8th to make a second request for administrative record documents. The motion includes the above points, but also makes it clear the city and the Mayor’s office have simply failed to produce documents that clearly relate to the arena proposal – for example, the Mayor’s “community alert” email that I reported on back in October was not included. Nor were the Mayor’s public Facebook comments in a discussion about the arena with residents in a group called “Eye on Inglewood.”

These missteps may seem trivial, but they point to a pattern of obfuscation and unwillingness to cooperate on the part of the City of Inglewood, the City Council, and Mayor James Butts. The point of CEQA is, in part, to prevent this type of obfuscation from happening in the first place by requiring public dialogue throughout the process of planning a development – not halfway through.

Time and time again, the city’s hellbent drive to push this project forward has smelled awfully foul, from insisting on eminent domain provisions in the ENA, to publicly spreading lies about their community opposition, to attempting to force a bill through the state senate that would carve up CEQA for the sake of a basketball arena. These latest developments certainly do not make the odor any more palatable.

This article was originally published on warrensz.me on January 10, 2018.