This week one of my tasks from @phillyhistory was to consider the pros and cons of large, medium, and small cultural institutions. For the purposes of this post I focus primarily on an example of a large and small institution. Larger institutions tend to have more sizable budgets than smaller ones, but this also seems to correlate to large institutions having more involved boards of trustees or directors who are averse to controversy of any kind.

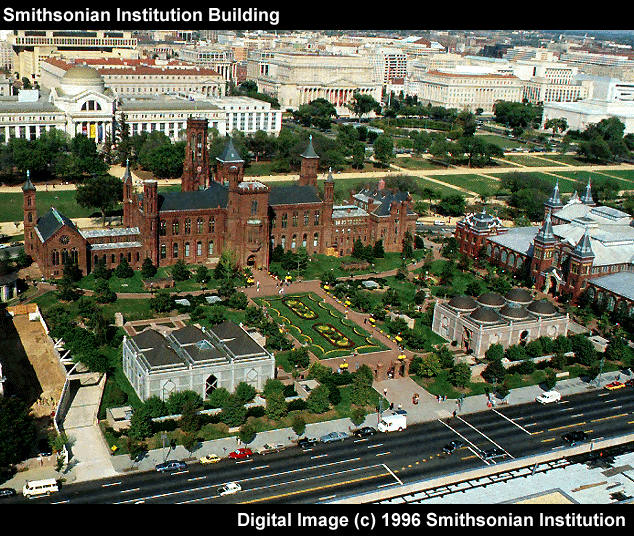

- Photo of the Smithsonian Institution.

One of the reasons for this apprehension stems from an infamous story from the 1990s when the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., specifically their museum of American History, developed an exhibit to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Enola Gay dropping the atomic bomb at the end of World War II. Before we delve into this scandal, let’s first examine the Smithsonian’s annual budget to see just what I mean when I call it a large institution. The Smithsonian’s annual budget, as of 2016, is $840 million. All of this money goes towards the nineteen museums that make up the Smithsonian Institution.

Now, back to the story: In 1994 the Smithsonian’s Museum of American History, after receiving criticism from veterans and members of Congress, made significant changes to their scheduled exhibit to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Enola Gay B-29 airplane dropping the atomic bomb. The revisions included omitting items that critics felt focused excessively on the negative effects of the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Since the Enola Gay debacle, many larger institutions, including the Smithsonian Institution have shied away from creating exhibits that could ignite inflammatory commentary from critics. So, although larger institutions tend to have significantly more money, they also sometimes are overseen by Boards who restrict how that money can be used.

- Photo of the William Way Community Center.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, however, are smaller institutions. When I think of smaller institutions, I tend to think that, despite having smaller budgets, they have greater freedom regarding the histories they interpret and how they do so. If you disagree, I would love to hear your thoughts below, but as an example I mention the William Way Community Center in Philadelphia, which houses the John J. Wilcox, Jr. Archives. In 2016 the William Way Community Center’s total expenditure was just under $1 million, and of that million, $723,269 went towards program services which includes various clubs, recreation, service programs, as well as educational programming based out of the archives. So although the entire Center’s budget runs around $1 million, only a fraction of that goes towards the archives and educational programming.

Still Fighting For Our Lives. The exhibit commemorates the thirtieth anniversary of the Philadelphia AIDS Library and presents the history of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Philadelphia and the activism that surrounded it. Included in the exhibit are posters of a man’s chest with “Sex” written on it containing information on safer sex practices, banners, photos, and other mementos from the 1980s and 1990s. Some of the materials on display were blatantly sexual, and when I visited the museum’s opening myself I found myself wondering if any larger institution, or rather any larger institution’s board, would support the inclusion of such materials.As for greater interpretive freedom, I think the best example of the William Way Community Center’s interpretive liberty comes in their recent exhibit, created in partnership with the Philadelphia AIDS Library and co-curated by @gvgktang, titled

Fortunately, the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum of American History organized an exhibit commemorating the thirtieth anniversary HIV/AIDS epidemic in 2010. The exhibit explained the “scientific aspects and social consequences of the AIDS fight and contains condoms, blood testers, explicit material on healthy sex and some posters with explicit language.” One interesting difference in exhibit design between the William Way Community Center and Smithsonian’s similar exhibits is how whereas the more sexually explicit materials were displayed throughout the rooms, the Smithsonian hid more sexually explicit materials in areas with “less traffic.” In another exhibition from 2010 the Smithsonian drew fire from the public, museum personnel, and artists when it removed David Wojnarowicz’s video “A Fire in my Belly” from their Hide/Seek exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery.

So it seems to me that the trope persists, that larger institutions either avoid or hide exhibit materials that could incite controversy while smaller institutions have more freedom to interpret and present their exhibits how they wish. What are your thoughts on this reader? Are larger institution’s boards justified in their apprehension or should they advocate for more difficult exhibitions that may incite controversy but also ignite important dialogue with visitors? Do you disagree with my assessment here and if so why? Let me know in the comments below!

click here.100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment is part of a graduate course at Temple University's Center for Public History and is exploring history and empowering education to endow meaning. To learn more

Sources:

Smithsonian Institution, “The Smithsonian Institution Fact Sheet,” Newsdesk: Newsroom of the Smithsonian, October 1, 2016. https://newsdesk.si.edu/factsheets/smithsonian-institution-fact-sheet (Accessed 2/19/18).

Neil A. Lewis, “Smithsonian Substantially Alters Enola Gay Exhibit After Criticism,” The New York Times, October 1, 1994. http://www.nytimes.com/1994/10/01/us/smithsonian-substantially-alters-enola-gay-exhibit-after-criticism.html. (Accessed 2/19/18).

GuideStar, Gay Community Center of Philadelphia aka William Way Community Center, 2018. https://www.guidestar.org/profile/23-7429170. (Accessed 2/19/18).

William Way Community Center, Mission & History. http://www.waygay.org/mission-history/. (Accessed 2/19/18).

GVGK Tang, "Project Showcase: Still Fighting For Our Lives,” National Council on Public History: History @ Work, January 15, 2018. http://ncph.org/history-at-work/project-showcase-still-fighting-for-our-lives/. (Accessed 2/19/18).

Claire Halloran, “Still Fighting For Our Lives: A Look Back on the History of HIV/AIDS,” WHIP Temple Student Radio, January 19, 2018. https://www.whipradiotu.com/still-fighting-for-our-lives-a-look-back-on-the-history-of-aids-hiv/. (Accessed 2/19/18).

Jacqueline Trescott, “’Hide/Seek’: Smithsonian Officials Look Back at What Went Wrong,” The Washington Post, November 23, 2011. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/hideseek-smithsonian-officials-look-back-at-what-went-wrong/2011/11/16/gIQAVkp8oN_story.html?utm_term=.3be0d10129c5. (Accessed 2/19/18).

I think you're absolutely right that smaller institutions usually come with more freedom, but I've also experienced smaller institutions being apprehensive to challenge the status quo because either they're paranoid about staying alive--and thus don't want to incite controversy--or they're run by small communities that don't have wide enough of a perspective to engage with challenging narratives. I'll probably explore that more in my own post. Thanks for sharing your thoughts, Derek!

Great post. I think the big vs small debate and the topic of that relationship correlating with the risk tolerance of an institution is spot on. Huge dinosaurs don't pivot on a dime.

However, I think your juxtaposition of the Smithsonian to the William Way Center speaks more to audience and different definitions of "public."

In DC the exhibits need to be broad and innocuous. At the William Way Center, off the tourist track in downtown Philly, the art has free reign because its within a safe LGBTQI space. So both spaces invite different variations of the public in terms of scale and diversity.

Non-profits are strange beasts and when you boil them all down, they are people driven organizations steered by a Board of Trustees.

Big Board = lots of egos, small Board = slightly fewer.

Thus, more people, more problems.

Here's my take on the topic: https://steemit.com/nonprofit/@peartree4/cryptocurrencies-and-non-profit-organizations-fad-or-future

There’s big and little in more ways than we maybe admit. Some smaller institutions, and some nonprofit leaders, are very open minded. And openness can feel like a form of bigness. And visa versa. Scale is only one factor in the test for “size.”