“Buildings broadcast a message. Good and bad architecture can lift or subdue the human spirit.” -Paul Joseph Watson

The disaster of Grenfell Tower, which took at least 80 lives, is just another enormous and longstanding failure of central planning.

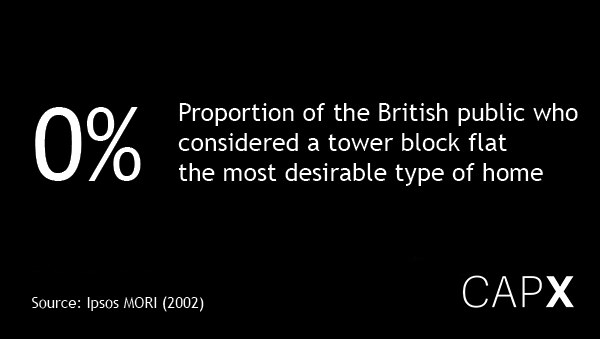

Opinion surveys in Britain, again and again, decade after decade, shows nobody wants to live in these enormous Grenfellian tower blocks. They want, by and large, traditional terraced housing with private gardens -- not forced communal space.

The formula is familiar: The people, the ones footing the bill, wanted something. The central planners, who took their money and promised to deliver, had their own agendas. The people received gruesomeness.

To date, over 4,000 tower blocks scar the British skies, blight the landscape in a hellish array. Most ugly, but all fighting for attention anyway.

The Tower Block Tenants Campaign has been railing for years about the insufficiencies and lack of upkeep: “cockroaches, asbestos, poor security, inadequate soundproofing, social isolation and a lack of play areas and communal facilities.”

Of many other complaints: The concrete is often of poor standard. The walls are normally too thin. The chemicals used erode the steel. Materials used didn’t fit well with the British climate. The buildings are increasingly fragile and difficult to escape from. And on.

They were so ugly, in an effort to spruce them up, the planners covered many of them in a type of aluminum paneling -- which, as they discovered with the Grenfell Tower -- is incredibly combustible.

The worst part? Tower blocks were a result of political social engineering.

THE RISE OF THE SOCIAL ENGINEER

It is no surprise the most renowned father of modern architecture, Le Corbusier, voluntarily served both Stalin and Vichy.

Like them, he thought he could shape the world and everyone in it to his liking. He is the embodiment of the twentieth century’s social engineering.

“We must create a mass-production state of mind,” Le Corbusier wrote in his book, Towards a New Architecture. “A state of mind for building mass-production housing. A state of mind for living in mass-production housing. A state of mind for conceiving mass-production housing.”

Le Corbusier lobbied for the construction of his giant brutalist tower blocks to be built on the peripheries of cities so to atomize and segregate the lower classes from the technocratic elite “experts.”

The politicians saw the vision. And thought that it was good.

Flush with State subsidies, of which Le Corbusier happily saddled, the dominant twentieth-century meme became speed over longevity. Timeliness over timelessness. Function over form. Brutalism over beauty.

Like Le Corbusier’s beloved reinforced concrete, “My reliable, friendly concrete,” as he called it, most modern buildings quickly crumble, stain and decay.

They are a result of incredibly short-term thinking, exacerbated by easy money and political largesse.

“Modernist architects had so little foresight,” Paul Joseph Watson says, “that after a short time, these tower blocks, streaked with water stains and infested with moths, mimicked and provoked the moral decay of their surroundings.”

To Le Corbusier, the individual was just another object to be put in its proper place -- in his “streets in the sky.” The individual exists everywhere as a collective, but belongs nowhere specifically. Which is why, in all of Le Corbusier’s prototypes, humans weren’t anywhere to be seen.

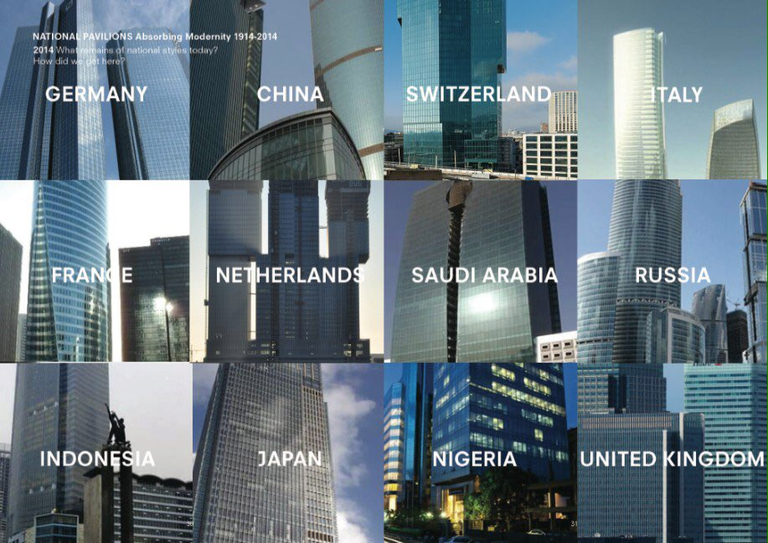

His message represented the hallmark of postmodern thought: Reject history. Reject tradition. Everything in the past deserves to be detested and deleted. Everything should be sameness in the name of diversity. Everyone is equal under a partial letter of the law.

Humans are not as they think, Corbusier demanded. They are as we think and make them to be.

Just like everything else.

“For Le Corbusier,” Anthony Daniels writes in his article, The Cult of Corbusier, “Man was no more than a machine for inhabiting a house, or rather a unité d’habitation. Everything was to be standardised, from space itself to teacups, with no individuality allowed or possible, because life for him was nothing but a technical problem to be solved by a single correct solution.”

Sound familiar?

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://lfb.org/grenfell-tower-technocratic-nightmare/

@chriscampbell

Great effort put up here!

Keep sharing.