One of the things that aspiring-mathematician kids struggle with when they’re on college, is to get use to the way of thinking that math at that level has. I’m talking about the subjacent logic of math and how we can use it to derive further results.

Let’s take a step back: during our academic life (through elementary and high school), in an average math course, we are taught repeatedly an specific formula or procedure: practice makes perfect, and the success that each one has (and the grade obtained) depends on the easiness with which we can recreate such procedure: summing, subtracting, multiplying, dividing, finding the x, deriving and finding the integral. Everything is reduced to a simple operation, whose result is achieved through a systematic sequence of steps following a preestablished set of rules. We, the mathematicians, don’t do that in our professional life.

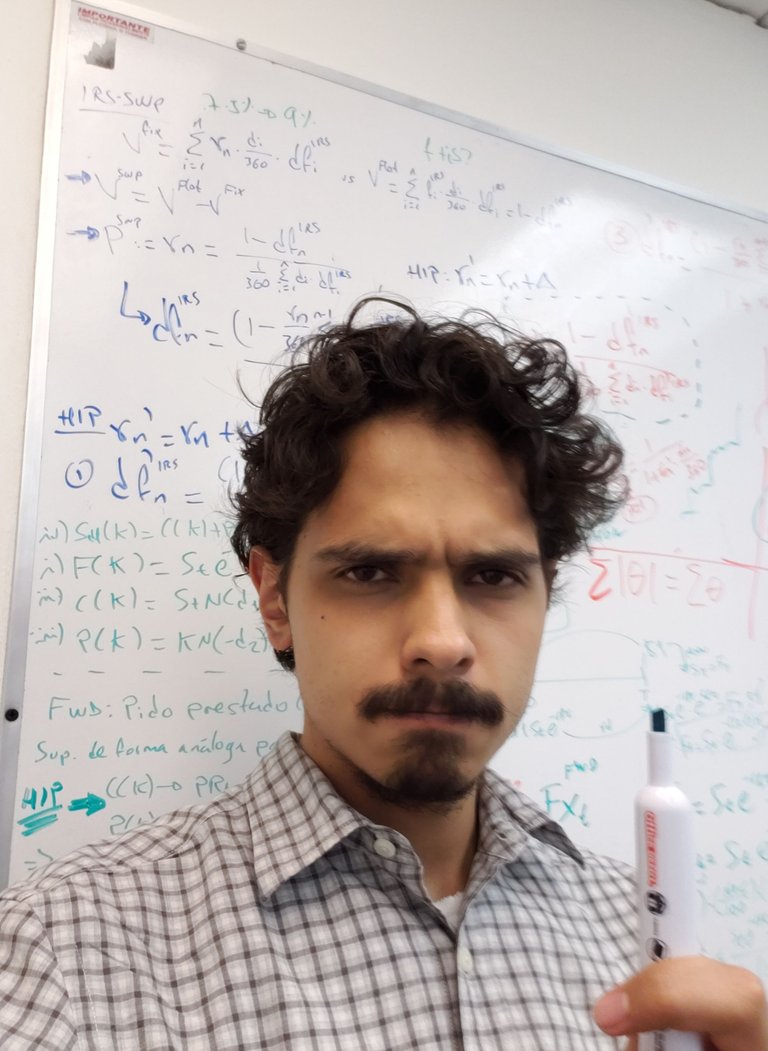

It’s frequent that when I tell other people that I’m a mathematician, immediately they remember those school times. Though they don’t say anything, I’m pretty sure they think I’m payed to find an x from a very difficult equation, or to derive a very complex function. Bewildered, however, people just ask me:

There are a lot of kinds of mathematicians, but those, as I, that have lived the privilege to do research on pure math, work to formulate a hypothesis, and then we try our best to reject it, prove it, and/or make it profounder.

Think, for example, on a chemist: he observes matter and, starting from those observations, he formulates questions. Then, he designs experiments trying to resolve those questions. Similarly, we mathematicians work. However, our field of study, is math itself, and our lab, a piece of paper and a pencil…at least for the pure mathematicians. Our final objective is to formulate a thesis and then to have an irrefutable proof of that thesis.

Una de las cosas con las que más batallan los aspirantes a matemáticos al momento de ingresar a la universidad, es acoplarse a la forma de pensar que tenemos nosotros, los matemáticos. Me refiero a la lógica subyacente que hay en las matemáticas, y cómo usarla para la posterior derivación de resultados.

Demos un paso atrás: durante la vida académica de la mayoría, hasta antes de los cursos universitarios o de grado (no sé cómo le llamen en tu país), en un curso de matemáticas promedio, se nos enseña a utilizar una fórmula o un procedimiento de forma repetida: la práctica hace al maestro, y el éxito que cada quién tenga en el curso (y la calificación que obtendrá), dependen mucho de la facilidad con la que podamos recrear dicho procedimiento: sumar, restar, multiplicar, dividir, despejar a x, derivar, integrar, etc. Todo se reduce a una simple operación cuyo resultado ha de obtenerse a través de una sistemática secuencia de pasos, sin salirnos de reglas prestablecidas. Los matemáticos no nos dedicamos a hacer esto.

Es frecuente que cuando le platico a la gente que soy matemático, inmediatamente les venga a la mente sus recuerdos como estudiantes. Aunque no me lo dicen en voz alta, seguro creen que se me paga por intentar despejar una x de una ecuación muy difícil, o intentar derivar una función sumamente compleja.

Desconcertados, sin embargo, solo alcanzan a preguntar, pero qué haces exactamente?

Hay de todo tipo de matemáticos, pero aquellos que hemos tenido el privilegio de dedicarnos a la investigación en las matemáticas puras, nos dedicamos a plantear hipótesis, y luego a intentar o refutarlas, o bien, probarlas y, de ser posible, hacerlas más robustas.

Piensen en un químico, por ejemplo. Él observa la materia. Y, partiendo de sus observaciones, se plantea preguntas. Luego, diseña experimentos intentando contestar esas preguntas. De forma análoga podría decirse que trabajamos los matemáticos. Solo que nuestro campo de estudio, son las matemáticas en sí, y nuestro laboratorio, una hoja de papel y un lápiz…al menos para los matemáticos puros; y nuestro objetivo último es plantear una tesis, y tener una prueba irrefutable de esta tesis.

I’d like to exemplify the last paragraph with some simple stuff of Group Theory (for now it’s not important to explain what this area of math deals with).

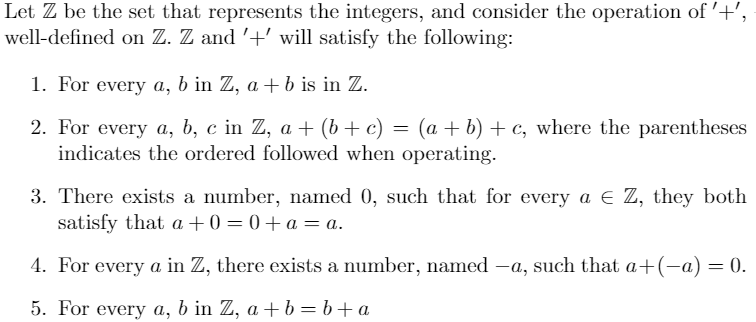

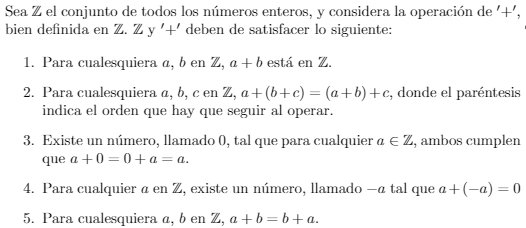

These axioms are the most immediate, intuitive and concise rules that we are going to follow. And as such, we will take them as granted. Hence, my dear reader, if I ask to you: what are the most immediate, intuitive and concise rules that you think numbers follow with their most basic operation: the sum? Well, forget for a moment everything you know about math and suppose that our whole universe concerning numbers is restricted to the following:

As I said, these axioms are the foundations and they will allow us to construct the rest of our mathematical building, and you might be surprised, but there are a lot of things we can say with these simple rules. The mathematicians study math itself, as the chemist studies matter. Thus what questions can we ask following this five simple axioms? What hypothesis could we formulate?

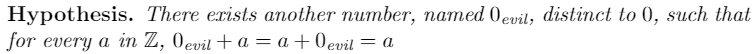

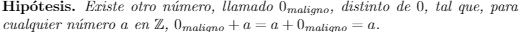

In the third axiom, for example, we could ask, is there another number that obeys the rule? Even if you consider it absurd (remember I told you to forget EVERYTHING you know of math for a moment). Formally, let’s formulate the next

Fortunately, our axioms are concise enough to prove that the existence of such a number is not possible. First, notice that all the previous numbers are restricted to the axioms already stated, including both the evil zero and the original zero:

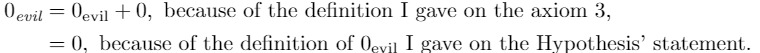

And this is a contradiction, because in the Hypothesis I said that this number, the evil zero, is different from the original zero! Hence, although, we failed to prove our hypothesis, we can state our first

This is a pretty standard technique that we, mathematicians, use--and you already know it!

We proclaim that something satisfies a proposition, then, we ask ourselves, is this thing unique? To prove that it isn't, we suppose there is another element, different to the first one, and then, through a series of steps using both our axioms as well as the other theorems we already had, we try to prove that this other element is equal to the former, hence a contradiction.

2 + 2 = ?

Engineer: 3.9968743

Physicist: 4.000000004 ± 0.00000006

Philosopher: "What is the meaning of 2+2?".

Logician: "Please define 2+2 and then you'll have my answer".

Economist: (he closes the door, the windows, and whispering asks): "how much do you want the result to be?"

@alonsomath: "Wait a second, I've proved that the solution exists and that it's unique...now I'm trying to find it at the limit..."

You could practice recreating this same exercise to prove the uniqueness of the numbers in axiom 4, that is, for every a in the integers, there is only a unique number, named -a, such that a+(-a) = 0.

Quisiera ejemplificar el último párrafo con unas cosas muy sencillas de Teoría de Grupos (por ahora no es importante explicarte mucho sobre esta área de las matemáticas).

Es común empezar con un sistema axiomático.

Estos axiomas son los reglas más inmediatas, intuitivas y concisas que vamos a seguir, y como tales, no las cuestionaremos. Por ello, mi querido lector, si yo te pregunto: cuáles son las reglas más concisas inmediatas y concisas que crees los números deberían de seguir con su operación más básica, la suma? Por un momento olvida TODO lo que sabes de mate y supón que todo nuestro universo numeral se restringe a lo siguiente

Como te dije, estos axiomas serán el fundamento que nos permitirá construir nuestro edificio matemático y, podrías sorprenderte pero, hay muchísimas cosas que se pueden decir y hacer con estas simples reglas. Los matemáticos puros estudiamos las matemáticas en sí, así como el químico estudia la materia. Así que qué preguntas se te ocurren podríamos plantear a partir de estos cinco axiomas? Qué hipótesis podríamos formular?

En el tercer axioma, por ejemplo, podríamos preguntarnos, hay acaso otro número que cumpla esa regla? Aunque creas que es absurdo (recuerda te dije que olvidaras TODO lo que sabes de matemáticas, por el momento). Formalmente, planteemos lo siguiente:

Afortunadamente, nuestro sistema axiomático es lo suficientemente robusto como para probar que no hay cabida para ese otro cero, pues nota que ambos ceros cumplen todos los axiomas que hemos establecido:

Ésta técnica es muy común que nosotros, los matemáticos, utilicemos--y ya sabes cómo usarla!

Decimos primero que algo cumple una proposición. Es muy usual que luego nos preguntamos, es ésta cosa única? Para probar que no, suponemos que existe otro elemento, distinto del primero y, a través de una serie de pasos usando ambos nuestros axiomas, así como los otros teoremas que ya hemos probado, intentamos demostrar que ese otro elemento es igual al primero: una contradicción.

2 + 2 = ?

Ingeniero: 3.9968743

Físico: 4.000000004 ± 0.00000006

Filósofo: "¿Qué quiere decir 2+2?".

Lógico: "Defina mejor 2+2 y le responderé".

Economista (cierra puertas y ventanas y pregunta en voz baja): "¿Cuánto quiere que sea el resultado?".

Matemático: "Espere, sólo unos minutos más, ya he probado que la solución existe y es única, ahora la estoy acotando..."

Si te interesa, puedes recrear la demostración ahora para probar que los números del axioma 4 también son únicos. Es decir, que para cualquier a en los enteros, existe un único número -a, tal que a+(-a) =0.

Joke explained: the number i is not a real number, and pi is the most famous irrational number.

There are other techniques that we use to prove or disprove other statements, depending on the nature of the problem, and through practice we sharp our mathematical gut to develope a natural ability to detect it ( the nature).

Another thing that we looove to do is to generalize things. For us, is not fulfilling to find something: we try our best to get to the most general case. That field of math that I talked you about (Group Theory), for example, is precisely intended to be a generalization of simple arithmetics: around 200 years of research beneath those simple five rules already explained!!

Because there are a lot of strange things that I could think about right now that will actually satisfy axioms 1-5. For example, let's define the following set with only two "numbers":

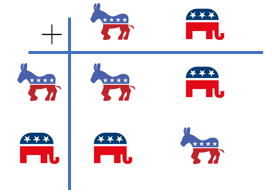

See this simple set as the equivalent of the integers, but now we only have two elements: a donkey and an elephant. And now consider the following table:

The way to read the table is pretty straightfwd. Since we only have two elements defining our universe, we must stablish the result of all four possible operations or combinations. Just read first the left side of the table, apply the operation, and then read the top of the table:

donkey + donkey = donkey

donkey + elephant = elephant

...

We could prove that this simple set is a Galois Group (the technical name that a set satisfying rules from 1-5 has), whose zero is the donkey! Hence, all the results and theorems achievable in an abstract and generalized way (e.g., uniqueness of the zero) are true for this simple mathematical object (e.g., uniqueness of the donkey). As I said, the magic of pure math is about generalization.

Hay muchas otras técnicas que usamos para probar o refutar proposiciones, dependiendo de la naturaleza del problema y, a través de la práctica, vamos afinando nuestro olfato e instinto matemático para detectar hacia qué dirección deben de ir los tiros.

Otra cosa que nos encaaanta hacer es generalizar. Para nosotros, no es satisfactorio encontrar algo: hacemos lo mejor posible para encontrar el caso más general. Ése campo del que te platiqué hace rato (Teoría de Grupos), por ejemplo, es precisamente un campo de las mates que busca generalizar la aritmética: hay alrededor de 200 años de historia investigativa y académica que giran en derredor de esas simples cinco reglas que ya te expliqué!

Porque, amig@ lector@, hay muchísimas cosas locas que se me podrían ocurrir ahora mismo que satisfagan los axiomas 1-5. Por ejemplo, definamos el siguiente conjunto con solo dos "números":

Ve este simple conjunto como el equivalente del que hicimos de los enteros, pero ahora, solo contamos con dos elementos: Maduro y Chávez. Ahora considera la siguiente tabla:

La forma de leer la tabla es muy sencilla. Dado que solo contamos con dos elementos que definen nuestro universo, debemos establecer el resultado de todas las cuatro posibles operaciones o combinaciones. Solo coge un elemento del lado izquierdo de la tabla, aplica la operación, y luego combínalo con uno del lado superior de la tabla:

Chávez + Chávez = Chávez

Maduro + Chávez = Maduro

...

Podríamos probar, de hecho, que este simple conjunto es un Grupo de Galois (el nombre técnico que tiene un conjunto que satisface los axiomas 1-5), cuyo cero, en este caso, sería Chávez! Así, todos nuestros resultados y teoremas que pudiéramos haber dicho en abstracto y de forma generalizada (e.g., a unicidad del cero), son ciertos para este caso muy particular con dos elementos (e.g., unicidad de Chávez). He aquí lo mágico de las mates puras: la forma de generalizar las cosas.

Amig@, no olvides votar si disfrutaste algo de esta publicación!

Si quieres conocerme ve mi

introduceyourself.

Si te gusta la filosofía, ve mi análisis de la otredad del meme

Si quieres aún saber más de mí, lee cómo apuñalé 23 veces a un cobarde pero otrora amigo

My friend, don't forget to upvote if you enjoyed anything of this post! Visit my introduceyourself.

If you like philosophy, read my analysis of the otherness of the meme.

If you want to still know more about me, read how I stabbed 23 times a coward but former friend

Yo también he lidiado con preguntas sobre lo que hago y lo que estudié, pero en mi caso, la explicación que doy (en la que explico que en mi carrera se aprende a pensar, a leer, a intentar darle respuesta a las interrogantes que nos hemos hechos como seres humanos desde el inicio de nuestra historia, y a cuestionar nuestros propios supuestos) suele ir acompañada de la siguiente duda: ¿Y para qué sirve eso?

Ugh. Es muy frustrante jajaja

Al principio pensé," wow, otra matemático", pero luego, viendo tu perfil, me di cuenta que estudiaste filosofía. Tanto una como la otra las une el mismo camino del pensamiento, o razonamiento. Saludos

Creo que fue ganadora hace poco en @decomoescribir :O

Filósofa, cantante, poetisa, escritora...hay algo que no sepas hacer?

No sé manejar bicicleta ni silbar :( jajaja

(Y tampoco soy muy buena en matemáticas)

Bueno, afortunadamente no necesited ninguna de ésas para ser exitosa aquí o en la vida...o eso creo...

Hola alonso. Te entiendo completamente; la misma pregunta me la han hecho cientos de veces. A pesar que yo me dedico a enseñar ( matemáticas) es el ámbito de la investigación donde los matemáticos podemos explayarnos. Los axiomas, hipótesis, demostraciones, pasar de la particularidad a la generalidad, me hicieron recordar mi paso por la universidad. Saludos amigo.

Hola amiga!

Pues sí, este post está dedicado con mucho cariño a nuestra profesión. Qué bueno que te pareció bien :)

Ahora me queda más que claro que las matemáticas junto con la filosofía aunque creo que los vemos como opuestos, terminan siendo complementos!

Un abrazo @alonsomath!

Sí, hay muchos matemáticos que también fueron filósofos a lo largo de la historia. Dos de mis héroes, por ejemplo: Bertrand Russell y Descartes :)

Loved it! I find maths fascinating although I gave up on it early on in high school because I was bored to death with the way it was taught.

Now I must go and look imaginary numbers up. ❤

And I love that you loved it♡

I'm glad that you are giving to math a second chance! :)

If you have a Discord account we could chat. Find me as @alonsomath

Cheers!

Don't have Discord... but maybe I'll try set up an account soon. All my hardware is highly jurassic and many things don't run well in it. We'll see!

Cheers!

Haha, ok!

As I suspected my 32bit old laptop won't work with Discord but the good news is that the browser seems to work ok - I've just finished setting up an account, as elisea of course :) but need a little time to explore it which I don't have at the moment - too much to do today in here today and no internet on my cell phone, but feel free to add me or something (do I need a server? - created one anyway (https://discord.gg/aaFeXcG)- I have no idea about what I'm doing there)...

Will be back later, to give a lenghty answer to your comment on my steemit username: I'm very passionate about language and names. ❤

I have the following comments:

Most steemstem members enjoy to read popular, easy to read, scientific content. ZF might already be a bit too abstract. In addition ZF is not very exciting for non-mathematicians. Maybe you can write about an abstract topic which has a clear interpretation but which also has strange implications like for example the axiom of choice.

I am guessing that you wrote this for a general audience. If that is the case you left some basic stuff undefined, e.g., what does it mean to be well-defined, what is an operation/operator.

Any type of picture on steemit (which is not yours) require a source. In addition, you can only use picture which can be commercially re-distributed. (So that also inculdes the meme and pictures of maduro and chavez)

It is always appreciated if you recommend sources for further reading.

I enjoyed reading it :)

Thank you so much for your time and observations:

The general purpose of the post was to explain to the general public how the average mathematician thinks and makes research through very simple examples.

I never mention the ZF axiomatic system because I acknowledge that even as exciting as it is for me, or in general to any mathematician, it is not for my target reader.

I agree that I left some things in the air and I was very informal with my explanation. I could have defined with all the formality an operation, as what it is, as a function, and explain that when we say that an operation is well-defined, it's because it satisfies that definition. Though, I wanted to keep motivated the reader,and be as intuitive as possible...most of my followers don't even have an engineer level of math.

This post was't even tagged with #SteemSTEM, although I asked for your opinion because I intend to write divulgative articles, such as this, for your community: I really want to be part of it!

I definitely agree, however, that I missed the sources, both for the images and for further reading, as well as ti check if the images are of public domain.

I sincerely appreciate that you took the time, as a PhD math student, to read it and give me some suggestions for the near future. And I'm glad you liked it :)

Muy Bueno! Me encanto el chiste xD y me pareció muy cómico la foto de Chávez y Maduro como conjunto. Me gusto mucho el contenido.

Muchas gracias por haberte dado una vuelta por aquí, y qué bueno que te hizo reír, jaja :)

Como le contesté a @bivianlg, lo escribí con mucho cariño para ambos: para los matemáticos, pero también para ustedes, los poquitos que me leen jeje

....aunque ya me regañaron por no usar citas :((

Saludos

jajajajajaja xD Tranquilo, de los errores se aprende :) Yo también soy relativamente nueva en esta página y la verdad, me ha costado un poco porque no soy de socializar pero bueno, ahí vamos! :D Espero sigas publicando contenidos de gran valor! :D

Gracias! Jaja, sí, a pesar de mi histriónica personalidad aquí, en realidad, soy también muy callado y tranquilo.

Pero sí, de a poco todos vamos aprendiendo :)

Gracias a ti por leerme!

Ay, me encantó. Yo estudio Ingeniería Civil y a veces me es muy difícil hacer converger la literatura y los números, pero luego encuentro que como vos, lo ha logrado éxitosamente :)

Muy buen post, no sabía que los matemáticos pensaran en Chavez y Maduro jajajaja! La mátematica y la filosofía son tan increíbles, tan asombrosas, una forma totalmente diferente de ver el mundo!

Me gusta mucho tu post, @alonsomath. Claro y divertido para los no matemáticos.

Con respecto al ejemplo Maduro-Chávez (como venezolano, no puedo dejarlo pasar), si le preguntas a un matemático del Ministerio de Ciencia de Venezuela, te demostrará que Chávez + Chávez = Chávez; Maduro + Chávez = Chávez. Si el Tribunal Supremo dictaminó que Chávez no estaba presente pero tampoco ausente, cualquier cosa es posible.

Leído en una pared de mi ciudad: "Larga vida a los matemáticos."

Saludos.