Hume infers from his insight that it is not reason but moral opinion that moves us to act, that reason is not the source of moral opinion. From this, he then further argues that moral opinion is a product of the passions – special emotions that arise out of the relations of ideas and impressions. In this essay, I will argue that Hume’s initial inference is correct, but that his subsequent inference is not. Passions may indeed arise from relations of ideas and impressions, but there is no good reason to presume passions, though necessary, are sufficient to produce a moral opinion.

So, what exactly is a “moral opinion”? Plato believed that opinion (doxa) was something that lay in the gray area between true and false belief. He argued that opinion did not deserve the respect of a truth because it lacked the justification of an eternal, unchanging quality necessary to rise to the level of êpistêmê (true belief). If we apply this standard to moral opinion, then, it would be a doxastic belief about the rightness or wrongness of an action, or the goodness or badness of a character. Moral knowledge, on the other hand, would be a belief of a much stronger type. To say, for example, that I believe stealing to be unpleasant, or that I wouldn’t do it, or that it seems wrong, would be to say something contingently true, relative to myself, and subject to correction. To say, “stealing is wrong”, on the other hand, is to make a truth claim asserting the real existence of a property in a certain class of actions. To make such an assertion, I would need to be able to identify the property, point it out, and name it. That would require some sort of perception, and perception requires a sense organ or a faculty of the mind, or both. Plato would rule out a sense organ as the source of our moral knowledge, because sensible phenomena are mere imperfect reflections of the ultimate reality of the form of the good.

The faculty of the mind that perceives such things as rightness or wrongness, according to Plato, is therefore a certain kind of judging faculty that need not rely on the senses. The traditional interpretation is to say that this is reason, and to make analogies to mathematics to bolster the claim because this is what Plato seems to do, but I disagree. In The Republic, Plato provides an ornate metaphor for his tripartite soul: that of a charioteer and two great horses. Plato puts reason in the charioteer’s seat, and assigns the role of appetite (passions) and judgment (moral judgment) to each of the two horses. This arrangement is important, because it speaks to Hume’s own assertion that “reason is and only ever ought to be the slave of the passions”. The charioteer is the apprehending ego, the “reasoning” member of the triad. He does not motivate the chariot. He only steers it. This is consonant with Hume’s view, that reason can only guide the passions, but where Hume fails is (to borrow Plato’s analogy), in thinking there is only one horse. Hume is presuming there is no judging faculty. With only one horse to pull the chariot, the best the driver can do is provide a bit of helpful guidance as the appetitive horse causes the chariot to careen in whatever direction its whim pulls it.

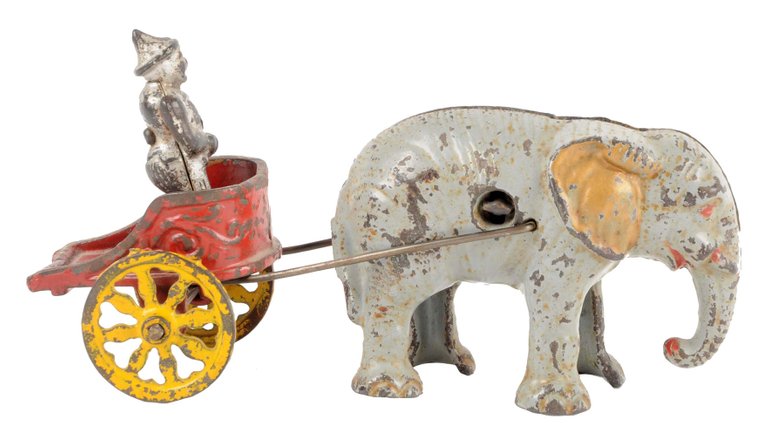

Jonathan Haidt, in his 2012 book The Righteous Mind, provides a more vivid metaphor: that of a thin, scantily clad tribesman mounted atop an unruly African elephant. In this metaphor, the elephant is almost entirely in control, and all the rider can do is suggest minor alterations in direction with a swat of reeds or a tug on a rope. His metaphor, like Hume, includes no faculty of judgment, no capacity to discern the difference between mathematical or empirical facts, and the normative consequences of actions taken in light of them. No capacity for selecting among possible goals. For Haidt, the elephant dictates the terms of engagement to the rider, and his only choice is over how enthusiastically he accepts them. Haidt is dutiful in his acceptance of Hume’s model of moral psychology. But Hume, as I have said, is wrong. Hume is indeed correct that the rider does not form his opinions on his own, but he is wrong to say that they necessarily derive from the elephant. Hume is ignoring the judging horse. Kant, reacting to his own observation of this problem, attempts to right the ship by overcorrecting in the opposite direction: he denies the importance of the appetitive horse, and gives control of the chariot exclusively to the driver. On Kant’s model, neither appetite nor judgment are empowered to lead us anywhere, and the charioteer is forced to get out and push the chariot, out of “respect for the moral law”. This will not do.

To properly form a “moral opinion”, as anything more than just opinion, requires judgment. Judgment is the reconciliation of “is” with “ought”, by means of a value determination. That determination requires a negotiation of experienced desires and reasoned principles. In this way, the rider and his two chariot horses have an equal say in the speed, direction, and ultimate destination of the chariot. For all it’s metaphorical mysticism, Plato’s model of the tripartite soul is a profound insight into human character that is lacking in almost all of his successors, save perhaps, Aristotle. The rational portion of the soul is the master of what is, the appetitive portion is the master of what I want to be, and the judging portion of the soul is the master of what ought to be. Our task, as thinking, self-conscious human beings, is to train ourselves so that these masters learn to live in harmony with one another. When we do, the result is eudaemonia.