Four months ago, I wrote a book review for Gerd Achenbach's book, Philosophical Praxis. Since then, I have been rereading the book and various chapters in it. Back then, I merely read the book in order to soak myself in its knowledge, wisdom, and insights.

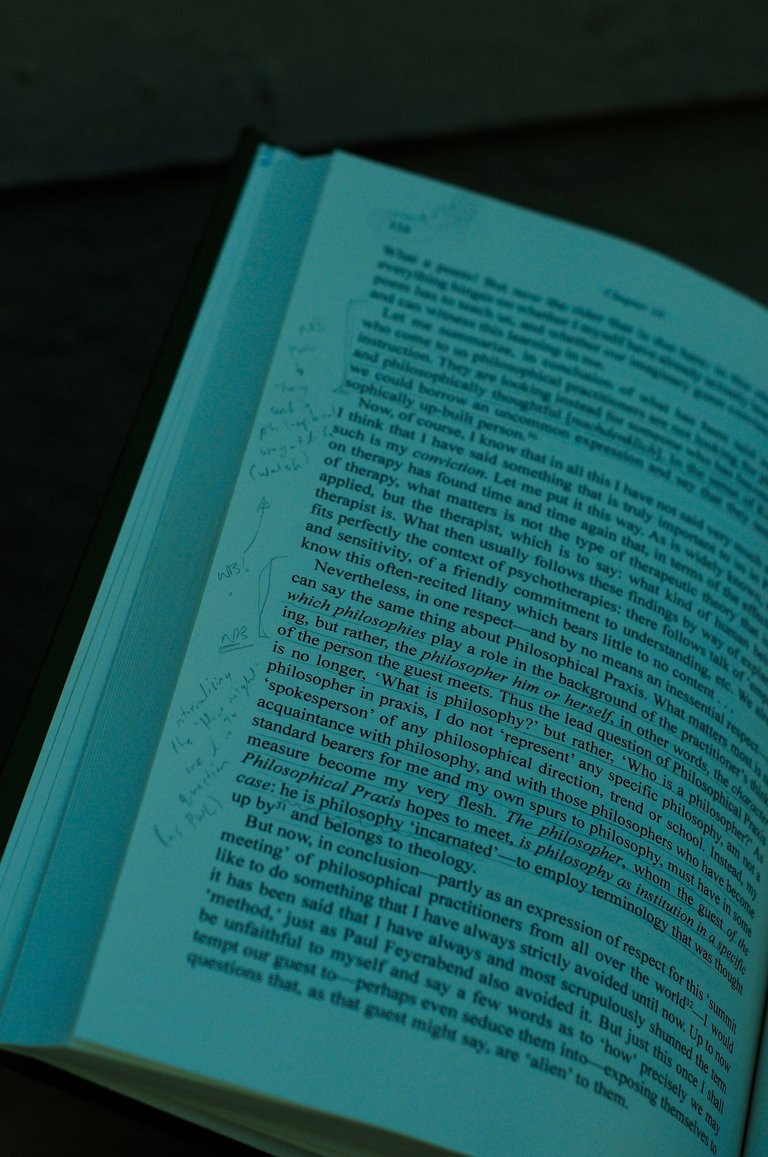

While indulging in the book, I constantly made margin annotations, underlining certain passages, circling page numbers and certain concepts. I tried to really grapple with the work.

And then a week ago, I decided it was time to write up these margin annotations in Obsidian.md. And let me tell you, this was a mission. It really took me a week to write, and with all of the quotations inserted, the document is well over 6 000 words. I really devoured the book, and the notes that I made branched into so many others. I could not stop once it began.

So, here I want to share with you this effort, this week long endeavour to write my own notes, and to see where it branched. This post will be long, and this will not be for the faint hearted. But this will be important for anyone who has a similar passion for bringing philosophy back into the public domain, to get the conversation going regarding philosophy, philosophical practice, and philosophy as a way of life.

Again, this is a warning, this post is overly long, so please do not try and read it one go. Let it ferment, let it sink in, and come back to it as you let these ideas marinade in your mind.

Without further ado.

Philosophical Praxis: Origin, Relations, and Legacy

Written by Gerd Achenbach

An unconventional and overly long discussion

(Or, Some frantic and mad notes)

NOTE: These notes were written by me,

the Fermented Philosopher,

and is by no means standard, universal, or "good". They are mere notes.

All of the quotations are taken from the 2024 translation, as found here.

Two main ideas of this book

One of the main ideas in this book is the by now all too known idea attributed to Gerd Achenbach that philosophical counselling is an alternative to therapy, and not just an alternative therapy (Achenbach, 2024:1). This stems from his idea that ...

"One who visits there wants neither to be treated nor cured [...] the visitor to Philosophical Praxis suspects that life is to be led, surmounted, mastered, if it is to come out well." (Achenbach, 2024:24)

A second idea emphasised throughout the book is the notion that philosophy and therefore philosophical counselling does not work with methods, but upon them.

"To speak correctly, philosophy works not with, but at best upon methods." (Achenbach, 2024:2).

Moreover, from this idea, that philosophy works upon methods, the idea of sabotage, and which I want to call methodological anarchism, stems. Here, the philosopher does not honour methods that was applied in the past, instead, she walks a new path, she tries and test alternative methods. The philosophical counsellor does not fall back into and onto what worked in the past, i.e., a clear method. It is important to note that ...

"every method teaches us to see something, but by the same token also to overlook something else." (Achenbach, 2024:155).

This is incredible insight in that method becomes a type of lens through which life can be seen. Method is discriminatory, it allows for something but then in the same breath disallows for something else. What disrupts the flow and security of the method, is overlooked.

The philosophical counsellor entangling herself with the irreducible counselee

Great emphasis is placed on the idea that the philosophical counsellor entangles herself in the world of the counselee (Achenbach, 2024:xxii).

Various instances throughout the book, emphasis is placed on the idea that philosophy and philosophical counselling/counsellors does not work with theories or methods, because this is not the domain of philosophy. Emphasis is placed on the counselee's unique situation, that cannot easily be reduced to theories or methods merely being applied to the counselee's situation. Hence the idea of the The Irreducible Counselee.

"the philosopher in practice takes visitors seriously [...] not as a mere ‘instance of a rule,’ but as this very one." (Achenbach, 2024:3)

Every philosophical counselling session will thus be different, unique, and based on different concepts and ideas. That is, every session, similar to an artistic moment, will be different. Achenbach goes so far to state that if this is not the case, that particular session would be a "very poor one" (Achenbach, 2024:85).

Interestingly here, one does not merely philosophise about the concrete, that is the lived life, but one philosophises out of the concrete (Achenbach, 2024:156).

The educational mission of philosophical counselling

There is an Educational Mission present, but there is no direct teaching in the strict pedagogical sense; instead, there is focus on personal transformation in which the philosophical counsellor embodies her practice. Additionally, it is about who the philosophical counsellor has become through her education or her time spent in the presence of philosophy:

"The question is whether the philosopher, through their own reading, has become wise and understanding and attentive," (Achenbach, 2024:3).

"it does not depend much, certainly not only, on what the philosophical practitioner knows or thinks, but on who he is—more precisely: on who he has become" (Achenbach, 2024:97).

One might linking this educational mission somewhat with the notion of the Ground Rule of philosophical counselling. Achenbach (2024:103) makes an opening thesis regarding who the philosophical counsellor has become:

The Ground Rule statement or thesis is that the philosophical counsellor cannot separate her own being from that of her practice; the scientist can go home at the end of the day, leaving her work so to speak in the office or the lab. The philosophical counsellor cannot do this, she is and has become her practice.

Becoming philosophy incarnated

This means that the philosophical counsellor cannot help but be what philosophy transforms him to become, that is, embodying his philosophical counselling practice.

This is also linked to the question, How Might One Live? which Achenbach (2024:103) phrases as how shall I live, which is a question that bugs the philosophical counsellor, and the counselee visits the philosophical counsellor because they also struggle with this question, that is, they also want to work through it.

Furthering the idea of embodied philosophy then here, Achenbach notes the literal becoming-flesh and incarnation of philosophy in the philosophical counsellor when they see philosophy not as in a "what is" type endeavour but rather who I as the philosopher can become through my engagement with the question of how might one live. Philosophy has "become my very flesh. The philosopher [...] is philosophy as institution in a specific case: he is philosophy ‘incarnated’" (Achenbach, 2024:124)

Very interesting is that Achenbach emphasises that only through co-thinking (or Collaborative Philosophising) can one really begin to help the counselee (Achenbach, 2024:3).

Experimenting with philosophy: The courage to think different, alternatively, otherwise...

Achenbach (2024:9) in some sense moves away from metaphilosophical discussions when he notes that we should rather experiment with rather than fix what philosophical praxis is. This reminds one a bit of Gilles Deleuze and the question of How Might One Live?.

Additionally, we can also not find ready-made answers and philosophical works in which the idea of philosophical praxis or practice can be found; we need to do the hard work and experiment with it, linking it to philosophising as a process, a moment, or an event.

"there is no place in the history of philosophy that Philosophical Praxis can find its bed ready-made, into which we need only slip to make ourselves comfortable." (Achenbach, 2024:11)

We are also reminded that philosophy tasks us and gives us the courage to think differently, alternatively, otherwise.

"philosophy thinks differently, and finally comes up with new thoughts, which is what is wanting." (Achenbach, 2024:14)

"philosophy is the courage to think differently" (Achenbach, 2024:26)

One might then here state that philosophical counselling is to help the counselee "think further and beyond" (Achenbach, 2024:141). That is, to have all the answers and insights beforehand is not what is needed.

But this thinking otherwise, to have the courage to think differently, might also become a burden, or it might begin to burden us (Achenbach, 2024:44). Trying to think about what really matters to and for us is not an easy task. Opening new pathways to walk on can easily lead us towards detours that might be both dangerous and fruitless (Achenbach, 2024:116; 117).

But this task of leading a different life leads to the most important realisation, and linking philosophy to the dangerous, namely, the fact that philosophy helps us open a conversation, overburdening one, to truly begin to think about what matters. This is a dangerous question, not only in disrupting securities of thinking (think of the dogmatic person who finds solace in her beliefs) but dangerous in the sense of taking potentially unfruitful detours. But this is necessary, as philosophy that does not challenge us, makes us the least bit uncomfortable, is not a philosophy worth its word and our attention (Achenbach, 2024:116).

Lebenskönnerschaft: Maybe phronesis, practical wisdom (?)

Achenbach provides us with a new concept to think about philosophical counselling, very similar to phronesis, which he calls "Lebenskönnerschaft". Here the notion of living well/mastering life becomes important. It is about questions that "moves one", that demands one to take seriously one's life, the one that you are living; and also that which pushes one to stand up for others, and what is "right" (Achenbach, 2024:44).

This also links nicely with the idea that philosophy and philosophical counselling is rather about leading a better life.

The gift of listening to and with the other

Another very important element in philosophical counselling is that of Listening. For Achenbach (2024:36), as one of the subtitles states, Listening is the soul of the conversation.

Listening is a skill that must be mastered (Achenbach, 2024:36). However, "conversational mastery begins once I have understood how difficult, extraordinarily rare, and hence quite improbable, genuine understanding is." (Achenbach, 2024:39)

The virtue of masterning conversation skills (that is, listening as activity and gift) is called by Achenbach (2024:39) Eingelassenheit.

Listening becomes pure activity (and not passivity) (Achenbach, 2024:37),

Listening in this active form can take on long and "deep" silences (Achenbach, 2024:37)

This reminds me of what another philosophical counsellor, Anders Lindseth, notes about Achenbach's practice, that is can sometimes entails deep "creeks of sighs" which stems from this deep listening or hearkening (Fastvold, 2005:173-174)

Listening attentively, i.e., really listening/hearkening, is to already and always rethink-through together, emphasising again the collaboartive nature of this practice, (Achenbach, 2024:37)

But importantly, this listening is not an attempt in making the other understandable, in fact, as Achenbach (2024:37) notes following Socrates, understanding and thus agreement prohibits and stops philosophising.

This also reminds me of philosophical counsellor Tillmanns (2005:3) who notes pretty similarly but adds a moral element to it, that attempting to understand and thus subsume the other's otherness or alterity is rooted in distrust.

Achenbach (2024:38) also talks about this in some sense when he says the philosophical counsellor should listen to the other in terms of how they want to be understood, even if this is a very difficult task and one that rarely works.

Listening together is to allow a freedom and togetherness to blossom so that the listener can gift the other space to talk freely (Achenbach, 2024:39).

"“I listen so that the Other will speak.” Thus, the listening that hearkens is “a hospitable silence” that invites the visitor to “speak themselves free.”" (Achenbach, 2024:39)

The notion of a gift lets me think about Derrida's notion of Hospitality and leads to what one might begin to call the Gift of Listening - the almost paradoxical state of radical reciprocity requiring both vulnerability to be changed by what we hear and an openness to receive without expectation of a return and also entailing an absolute surprise that might ruin my own home or lead to a death.

Returning to the Ground Rule of philosophical counselling

Achenbach (2024:51) begins to talk about what he calls the Ground Rule of philosophical counselling or practice, which is essentially that philosophical counselling, if taken seriously, is not about "the philosophical," but rather about the "non-philosophical"

"the opening move is not made by philosophy; the opening is made by the questions brought to the philosopher." (Achenbach, 2024:51)

Achenbach (2024:60-62) reads a short passage of Bertrand Russell regarding the "worth" of philosophy and comes to a couple of interesting and good conclusions:

The effects of philosophy on the philosopher is where its worth lies (i.e., Philosophy as a way of life)

Those who accepts this way of life, lives "differently" (Achenbach, 2024:60). (Interestingly, Pierre Hadot who also wrote about this notes that philosophers was different, they dressed differently, and so on.)

The value of philosophy is in its relation to uncertainty (this is very important, that is, Philosophy and Uncertainty); it is a tool to help us better cope and live with uncertainty, as this is all that there is (Achenbach, 2024:61).

This is also linked to the idea of All that philosophy has to offer in the sense that we are not "deceived, neither by others, nor by the ensemble of the real (which presents itself as if it could not be otherwise)" (Achenbach, 2024:61)

Philosophy as an end in itself: A conversation between the counselee and the history of philosophy

Philosophical counselling is an open-ended free conversation, leading one towards the idea of Philosophising as an End in Itself; that is, the goal of philosophical practice is to philosophise (Achenbach, 2024:84).

A very important role of the philosophical counsellor is to facilitate a conversation between the counselee and philosophy itself, that is, rather than Socratic questioning aimed at someone or something, the role is reversed so that the counselee begins to question philosophy, posing their questions against the philosophical counselor.

It is no longer the case, similar to Socrates, that the philosopher asks serious and tough questions; instead, it is the counselee who asks serious and tough questions to philosophy itself (Achenbach, 2024:86).

Moreover, as Achenbach (2024:90) tells us, it is not about what we know, but rather what we can make with this skill of traversing the vast network of ideas, it is about being able to know our way, living well in this "second home" of sorts.

He especially links this idea with living in more than one world, and having many "virtual contemporaries" with whom one can converse and engage with (Achenbach, 2024:91-92).

This effectively keeps philosophy (the history of philosophy) alive to those who dare to navigate its sometimes rough waters. This also links with the interesting idea of a Living Past contrasted to a dead past. Here, the philosophical counsellor can help the counselee read the history of philosophy in such a way as to help them "create" new connections and concepts; there is not only one "correct" way of reading a text.

For example, Achenbach (2024:92) writes that, "For Kierkegaard, Hegel lived; for Kierkegaard, he was present and alive like no one else!"

Moreover, this link to education is emphasised again in terms of not being a lecture that the philosophical counsellor gives the counselee, nor something they can verbatim recite, instead, "whether the philosophy we have been able to appropriate has really become our own is proved [...] only by our understanding through it!" (Achenbach, 2024:95). Again, this links with the idea that philosophical needs to transform our very being in the world.

The philosophical counsellor learning from the counselee/guest

Yet another crucial idea that Achenbach (2024:96) gains from Kierkegaard is that the true teacher learns from the student, not necessarily in what it might immediately mean, but importantly in the sense that the teacher tries to understand what the student at that moment might understand.

This links to the important idea, concretised in the book by Patrick Casement, that we begin to "Learn from the patient" or in this case the student or counselee.

Philosophical counselling is also important to help the counselee verbalise and think through what they are themselves saying but also thinking:

"Philosophical Praxis is all about getting people to understand what they are themselves saying" (Achenbach, 2024:125).

Postscriptum, or An Overly Long Discussion on a Strange topic

This is a strange discussion in a unique corner of philosophy. I am not even sure if anyone will ever read this. But it might serve as a kind of depositing of ideas that might spur on other conversations whoever might stumble upon the ideas.

For now, happy reading and writing.

All of the musings, writings, and thoughts are my own, albeit based on the work of Achenbach. These are thus my reading notes based on this book. The quotes are not my own, and come from the book hyperlinked at the start. The photographs are my own, taken with my Nikon D300.