Was the daguerreotype for real?

Joseph Saxton had heard about the recently-announced invention from Paris. He wondered: could this process actually allow anyone to replicate scenes in infinite, accurate detail without any artistic training?

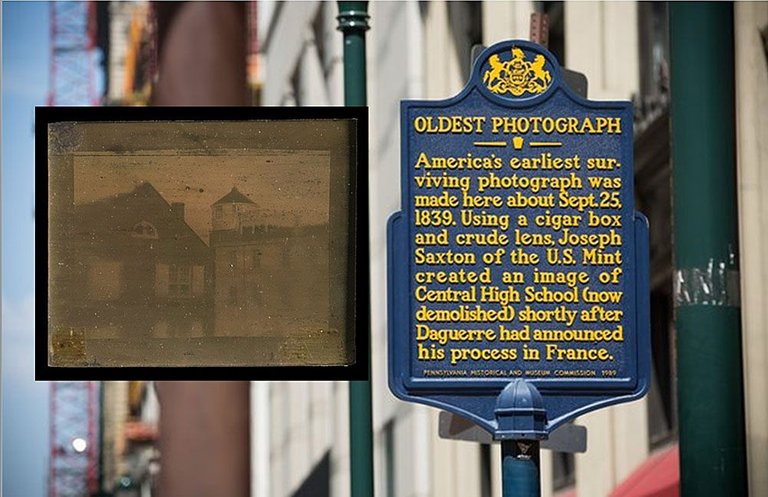

- Historical marker at the site of the United States Mint (Source) and (inset) Saxton's Daguerreotype (Source)

“A new edition of the famed moon-hoax," claimed one chemistry professor, “an intrinsic improbability.”

Saxton wasn't quite as skeptical. And when he read “The Daguerreotype Explained.” in The United States Gazette on September 25, 1839, he thought he understood what Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre had accomplished.

This was no hoax. Nor had Daguerre perpetrated any kind of a magical illusion. The daguerreotype was real—a new, potentially transformative technology.

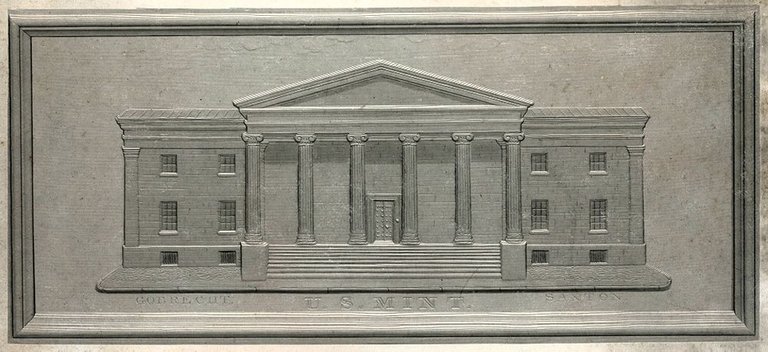

- The United States Mint. (Source: Jacob R. Eckfedlt & William E DuBois, A Manual of Gold and Silver Coins of All Nations)

Saxton, an official at the United States Mint in Philadelphia, had skin in the technology game. He read the newspaper account closely: Start with “a sheet of copper, plated with sliver;” expose it to “the vapour of iodine;” place it in “the camera obscura;” develop it with “the action of the vapour of mercury” and finally, stabilize the image by dipping the plate “into a weak solution of hypo sulphite of soda.” Finally, wash it “with distilled water.”

“The progress is now complete,” promised the article’s anonymous author, “the plate presents a drawing in which the light and shade is truly represented.”

"OK," thought Saxton. "I can do that."

And he did. Not once, but several times over the next few days.

This we know from Marcus Aurelius Root, a successful and prolific daguerreotypist in his own right, who told the story alongside his own reminisces, The Camera and The Pencil, published in 1864:

“Joseph Saxton, a cultured man of genius … carefully examined the... subject, and had concluded that Daguerre's announcement was literal truth. He forthwith proceeded to experiment in the art…”

According to Root, Saxton “constructed a camera by fixing an ordinary sun-glass in one end of a cigar-box; while a Seidlitz powder box, with an aperture in its top somewhat smaller than the plate to be used, and containing a few flakes of dry iodine, served as a coating box. His mercury-bath was made by excavating a hole through a dog wood block, and attaching thereto a piece of sheet iron so bent, as to hold a little quicksilver. And finally, for a plate, he burnished a piece of silver one and quarter by two inches in size.”

- “The earliest surviving American daguerreotype.” (Source: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania

“With these primitive implements he produced that day, the first heliograph ever made in Philadelphia…”

Root continued: “I have in my possession another view taken by him, soon after, from the same window, and representing certain buildings west of Broad street. It was presented to me by Mr. Saxton himself.”

Yet no one has ever reported seeing this, or any other Saxton daguerreotype.

Are they out there?

Digging deeper, looking for clues, we find another account, published about thirty years after Root’s:

In 1892, Julius F. Sachse described “Philadelphia’s Share in the Development of Photography,” at the Franklin Institute. (PDF) “The ingenious Saxton set his apparatus on the window-sill of one of the second story north windows of the Mint, and pointed it northeastwardly toward the sunlit buildings beyond” and “to the great…joy of the experimenter, the attempt resulted in a perfect picture.” Saxton “proved the truthfulness of the published account of Daguerre’s invention” successfully making “the first heliograph in America.”

“On the next day," Sachse added, "Saxton succeeded in making several other pictures of different buildings, all of which were taken from the same window.”

There may be more than one out there? Possibly two or three?

Other than these two credible written accounts, no one has ever seen or heard of any.

The first Saxton daguerreotype, which historian of photography Helmut Gernsheim called “the earliest surviving American daguerreotype” has long been at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. But the second earliest? The third? They may still be out there, unidentified, uncollected, unappreciated, and drastically undervalued.

A note to all history hunters: Take a good look at what Saxton was capable of in September 1839. Make a note of the dimensions of the single modest plate (2 3/4 by 2 7/32 inches) that survives. Keep in mind that Root used the plural when he wrote “these heliographs naturally created no small excitement among the curious in such matters…”

The discovery of the long lost Saxtons—more than 178 years later—would once again stir “no small excitement.”

Certain fame and fortune await those who find the missing Saxtons, America’s earliest daguerreotypes.

Good photo good post :) so nice keep going :)

I intend to @crazy3! Thanks for visiting!

Really enjoying these writeups of yours . Keep it up . This post has been deemed resteem & upvote worthy by your friendly @eastcoaststeem ran by @chelsea88 (not a bot)