Lee Friedlander's "The American Monument" was first distributed in 1976. That is "landmark" particular, however a numerous solitary aspect regarding Friedlander is that he's nothing if not a pluralist. Whitman-like, he is extraordinary, contains hoards. In a paper affixed to the extravagant new release of this historic point work, Peter Galassi (who curated the 2005 Friedlander review at the Museum of Modern Art) regards it "silly" to attempt to check correctly what number of books the picture taker has distributed since 1976 preceding settling on about one a year. The review was tremendous, and, definitely, the going with inventory was excessively robust, making it impossible to drag home serenely. It was kind of amazing, however landmarks have a tendency to be raised to the dead.

On receipt of a lifetime accomplishment grant from the International Center of Photography in 2006, the 71-year-old Friedlander reacted that the respect, while welcome, was untimely. At the marvelous gathering and supper, he spent the night shooting, snapping visitors and alternate honorees like an offspring picture taker anxious to capitalize on what may turn out to be his enormous break. That break really came in 1967 at MoMA when he, Garry Winogrand (who kicked the bucket in 1984) and Diane Arbus (who passed on in 1971) were spoken to a move in narrative photography from social worries toward more individual finishes. It's conceivable that his notoriety, as it has ascended in the decades since, has likewise endured, in the way that Dizzy Gillespie's did in examination with that of his bound kindred bebop pioneer Charlie Parker.

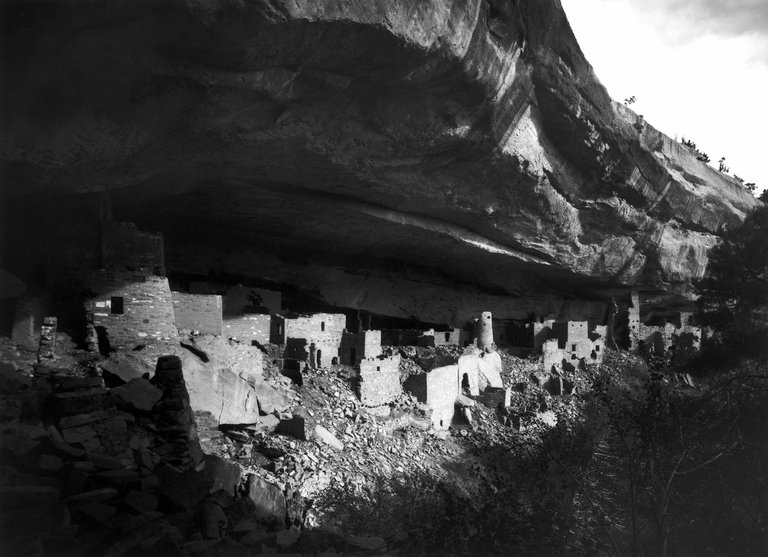

Inevitably for an aesthetic profession extending over five decades, the nature of the work is uneven. Not at all like Winogrand, Friedlander hasn't abandoned altering, however he is more inspired by taking pictures and getting them out than in circumspectly curating his own particular oeuvre. "It's a liberal medium, photography," he is cited as saying in the epigraph to the MoMA inventory. He was thinking especially about a photo of his uncle, which additionally incorporated a bundle of other, unintended data. "The American Monument" came to fruition in comparative design, when he saw that dedications and statues of different sorts sprung up in numerous contact sheets, some of which were principally worried about different issues. From that point forward, he started searching out such landmarks over the span of his goes all through the States. Inevitably he had enough pictures for a book — which, in Friedlander-ese, implies all that anyone could need. The first release bubbled a huge number of potential competitors down to 213, the main part of them taken in the vicinity of 1971 and 1975, supplemented by a splendid afterword by Leslie George Katz. That article still feels astoundingly crisp in the republish, despite the fact that Katz's perceptions once in a while glimmer with a confidence in the suspicion of the proceeded with worth of landmarks that may end up being "defamed," "old fashioned" or amusingly apt, as when he says of their energy, "Something like racial memory is grinding away."

Robert Musil composed that nothing is as imperceptible as a landmark, and Friedlander in the 1970s savored the basic and complex undertaking of making the undetectable unmistakable. He did this by demonstrating how landmarks stow away on display: subsumed by movement, by nature, by the plenitude of coincidental detail he "got" in that photo of his uncle. The artist Siegfried Sassoon communicated the brutal mystery of recognition while thinking about the Cenotaph, devoted to the dead of the First World War, in London: "Influence them to overlook, O Lord, what this Memorial/Means." Friedlander's photographs perused like a nearly arbitrary study of the style and implications of a wide range of landmark — and of the fact that it is so natural to overlook what is intended to be recalled.

It is completely circumstantial that the book is being reissued when the noiseless cases of landmarks on our consideration have turned out to be more discernable than at any period in their long and lethargic history. Second thoughts around a couple of make us recently mindful to the numerous. The collection is basically the same as it was in 1976, yet we see it rather in an unexpected way. Landmarks, all things considered, are additionally reflects. Along these lines, so far as that is concerned, are the windows (regularly of autos) through which we see them — and couple of picture takers have a great time than Friedlander misusing, investigating and thinking about the limits of these two bits of innovation to convolute what is appeared in a casing. Reliant on all way of reflecting, both well suited and invented, the thin volume Friedlander distributed before "The American Monument" was a gathering of self-representations. The self of which the photos in the republished book offer a composite representation is, obviously, America.

By another occurrence, the title of the last picture in the book peruses: "Brigadier General Albert Pike. Washington D.C. Presently evacuated." If Pike's statue were any more far off, at that point photographically it should not be there. Not at all like the walkers hustling toward it, the statue has no expectations of going anyplace, however outwardly it's as of now in transit out. A sign says, "STOP"; still photos do that to time however not to history. In the years since it was taken, the Pike photograph has turned into a record of a now-truant remembrance: safeguarded confirmation of its passing.

In setting up the new release, an analyst for the Eakins Press recognized another 10 or 11 statues in the book that are, contingent upon your perspective, either imperiled or static criminals from verifiable equity. I presume various individuals encountered a startling pull of sensitivity when President Trump bemoaned "the evacuation of our excellent statues and landmarks" remembering the Confederacy, regardless of whether, judiciously, they perceived the requirement for such a winnow. Neighbors perhaps felt a similar path in Argentina when the generously old chap who lived first floor was captured as a war criminal. The distinction, clearly, is that the statues are out there in the open as though they don't have anything to cover up. Treading a scarce difference in lawful amenities, they request to a jury made up, halfway, of individuals who have known them for a considerable length of time: Am I complicit, the statue solicits, in the deeds or perspectives from the man in whose picture I have been thrown and caught? Planning to be conceded insusceptibility from arraignment, their exclusive expectation is to induce us that, throughout the years, they have turned out to be changeless inhabitants of late history instead of emblematic delegates of a more inaccessible and blameworthy past.

Striking photos have just been made of what can occur after contentions for a stay have depleted themselves. Pulled from his platform outside the province courthouse in Durham, N.C., a Confederate warrior lies drooped on the grass as though disappeared by two sorts of time: one new (and less respectful), the other immemorial, in a manner of speaking. This emblematic "passing" offers a potential political trade off amidst the present cleanse. Truly, the statues can remain — yet just in the event that they are unseated and left to take their risks in the midst of the fallen clears out. Give them a chance to wind up images not of administration to the Confederacy but rather of the forsakenness of bigger municipal obligation.

The emptied plinths or spaces once in the past involved by statuary offer ascent to another photographic probability whereby the landmarks' felt nonappearance may be recorded and gaged. Whole surroundings are modified by this nonattendance — for a begin, they're not any more environment! Such a venture would be an upset expansion of Joel Sternfeld's "On This Site" (itself reissued, in 2012, by Steidl), in which photos move toward becoming remembrances of abominable occasions that happened in until now unmarked spots. It would likewise constitute what may be named a certifiable adaptation of Michael Somoroff's "Nonattendance of Subject," in which the subjects of some of August Sander's pictures — including a Nazi fighter — are carefully evacuated so just the foundation remains.

Friedlander has dependably been a craftsman with a solid feeling of photographic history, of carrying on — and saving — crafted by the individuals who preceded. That may be the reason he took a photo of the statue of Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman and his steed in Vicksburg, Miss., that had been captured by Walker Evans in 1936. The concentration, in Evans, is tight, without setting or foundation; Friedlander appears, actually, the cluttered potential outcomes that lie past the casing of Evans' unobtrusively thorough tasteful. All the while, the producer of "The American Monument" develops an attentive and speedy — as in the snappy and the dead — photographic remembrance to the maker of "American Photographs." A sign in that photo of Albert Pike understands, "ONE WAY," however the convention of any fine art must work both ways in the event that it isn't to end up noticeably an ossuary or a sequence of tribute. The last expressions of the last inscription in the book — "Now expelled" — additionally signify "To be proceeded."