Before coming to live in Japan to be a farmer I used to work in France in the spirits (armagnac, calvados, cognac, whisky etc.) industry. One of the many different roles I played was as a photographer for Whisky & Fine Spirits Magazine, visiting many different bars, breweries and distilleries, not just in France but also in Germany, Italy, Scotland, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and Wales. Anyway, here is the third post in the series of photos from those trips, taking you to the Domaine de Chez Maillard distillery in France, producer of the ABK6 and Leyrat brands of cognac brandy.

Cognac: distilled wine from the Cognac region

One of the most heavily-marketed spirits in the world today, Cognac is at once both very simple and extremely complicated. In essence distilled wine (as opposed to whisky which is essentially distilled beer), made by boiling wine so as to concentrate the alcohol it contains, and then aging that for a number of years in oak barrels, Cognac is distinguished from other similarly made spirits by the fact that it is made exclusively in the Cognac region of France. In other words, you can make wine, distill it and then age it in oak casks anywhere else in the world (including elsewhere in France), but you cannot call it Cognac. In fact, even bringing wine in from elsewhere distilling it in the region and calling it Cognac is not allowed: Cognac can really only be made from wine both vilified, aged and distilled in the designated region.

Domaine de Chez Maillard: unlike most other Cognac

Another particularity of the Cognac eau-de-vie (the French term - meaning “water-of-life” - for spirits) is the fact that the vast majority of bottles (and brands) sold are blended from spirits produced in many different distilleries. While this is also true of Scotch whisky (think of Ballantine’s, Bell’s, Chivas, Cutty Sark, Dewar’s, Famous Grouse, Grant’s, J&B, Johnny Walker, Teacher’s etc.), the single malt scotch whisky category helps to balance things out and provides enough choice for serious amateurs (think Balvenie, Glenfiddich, Glenmorangie, Laphroaig, Macallan etc). Cognac sold as single-distillery bottling (so to speak) is, however, very hard to find, being mainly sold as blends of different eaux-de-vie from different distilleries in the different sub-regions of the Cognac area (think Courvoisier, Hennessy, Martell, Rémy Martin etc). The cognac produced by the Domaine de Chez Maillard distillery belongs to this category, being sold under one of two main brand names: Leyrat and ABK6. The first brand name, Leyrat, is reserved for premium bottlings (single casks, vintage etc.) whilst the ABK6 label - named after the Abécassis family who own the distillery - is used for more generic versions. Either way, as producer and as a brand owner, the Domaine de Chez Maillard is definitely up there in the (genuinely real, not simply perceived) premium category, so I was glad of the chance to get to know the entire package: vineyard, distillery, aging warehouses and finished bottled product.

Traditional charentais pot stills

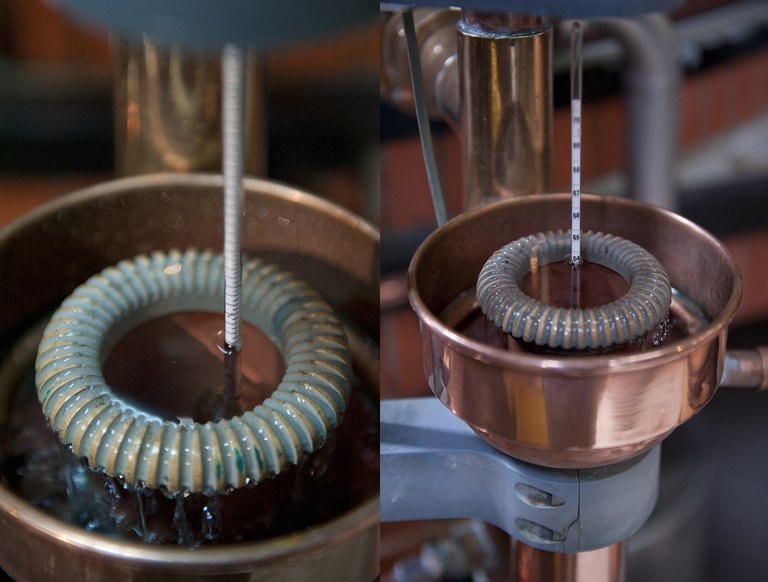

One of the many other conditions governing the production of genuine Cognac (alongside the geographical delimitations etc.) is that all the eau-de-vie be produced in traditional charentais pot stills. The word charentais is simply an adjective, qualifying anything from the Charentes region which, broadly speaking, corresponds to the area of Cognac production. In other words, the charentais pot still is the pot still of the region. Because the region is known for its distilling know-how, these stills are often seen outside of the area, and have been adapted for use in other distilleries all over France (for example, in the Calvados region, cf. my post on the Lecompte distillery, linked to at the bottom of this page) where they are often used in tandem with other types of still. In Cognac, however, only the charentais still is used and allowed. Somewhat smaller than the average whisky Scotch still, the two parts of the charentais pot still really are shaped liked an onion: the red heater sitting high a-top a brick column, and the copper-coloured still encased in a lower brick housing, sitting over a fire box.

Unlike in Scotland, where the law makes it necessary to keep all parts of the alcohol production process under lock and key, in a Cognac distillery it is common to see the spirit flowing off the still through an open well where a hydrometer floats, slowing moving up and down as the ABV ("alcohol by volume") goes and up down throughout the distillation. This means that it is relatively easy to draw off samples - from an adjoining pipe used to fill casks for aging - to taste in order to monitor the quality. Accompanied as we were at this point of the trip by the distiller, we were lucky enough to taste some for ourselves.

Rich and strong (roughly 60 percent ABV), but at the same time mellow, fresh and fruity, un-aged Cognac straight off the still is well-worth trying and makes you realise just how bad some of the big-brand Cognacs really are: if it can taste this good before it is even aged, how on earth do they manage to turn it into something so bland and monotone?!

Inside the aging cellars

Most French distilleries that age their own product have two kinds of aging facility: a regular cellar warehouse for aging their regular stock, and a separate cellar, called the paradis (“paradise” in French) reserved for the sole purpose of aging their very finest and rarest eaux-de-vie. While the regular warehouse is usually open to the elements, the doors lying open to allow air to circulate, the paradis is often hidden away behind locked gates, purposefully rendered dark and inaccessible, the cask lying sleeping beneath thick layers of dust and cobwebs. While obviously only the oldest distilleries have the oldest stock, it is still common - as it was at the Domaine de Chez Maillard distillery - to find casks dating back to the 70s and the 60s in many small, family owned distilleries.

In fact, in many eau-de-vie producing regions (Armagnac in particular), small families often lay down casks of spirit to age as a future investment: to pay for the future wedding of a daughter, for example, or perhaps to buy a son a car for his 21st birthday. However, while the big producers tend to use their very oldest spirit in blends (take Rémy Martin with their Louis XIII luxury version, for example), only the small, family producers regularly bottle their oldest treasures as they are, making small distilleries like Domaine de chez Maillard much more interesting to genuine amateurs in search of the finest, oldest, most complex eaux-de-vie. Oh, and clambering over and through the casks, trying to find something really spectacular, is a great experience, too (in the left-hand photo above, at the very back of the cellar, you can just see a colleague doing just that)!

Tasting some finished samples

While tasting samples direct from the still and pulled from the cask is great fun, it is not necessarily the best way to understand the philosophy of the distillery owners and marketers. After all, as I said above, the big, multi-nationally owned distilleries also produce good spirit, they just choose to blend away it’s character and sell it as relatively boring and bland - but no doubt more easily marketable - sugar, alcohol and fruit juice (well, that’s how I see it anyway…). So, tasting the finished product, or at the very least bottled samples, is not just a pleasurable experience, it is a very educational one, too.

Because the Abécassis family who own the Domaine de Chez Maillard estate and distillery have chosen to do everything in house, they not only have their own master distiller, they have their very own master-blender/cellar-master also. Christian Guérin, born and raised in the Cognac region, started his career working for one of the Château Crozier Bage, a grand cru Bordeaux wine producer, before moving back to Cognac to work in various laboratories and then to the Domaine de Chez Maillard in 2012.

As maître de chai (cellar-master in French), Christian’s job is to keep an eye on stock, making sure that nothing spends more time than is ideal in cask (relatively new casks in particular can have a very strong influence on new spirit: if left in contact for too long, the character of the oak casks can become dominant, overpowering all the fine notes of the spirit itself) and that there is always sufficient stock to cater to demand; as maître-assembleur (master-blender in French), it is his job to use that very same stock to its best advantage: sometimes that means blending together young and old spirits (marrying youthful fire and character with more mature complexity and elegance for example) and bottling the result at a reduced strength; sometimes it means bottling an exceptional cask as it is, neither blending it with any other Cognac, nor reducing the alcoholic strength, or even chill-filtering. [cf. note 1]

The results can be quite spectacularly different, considering how everything comes from wine made from grapes grown in the surrounding vineyards, vilified in the same building, distilled in the same stills and then aged in the same warehouses. From a light, simple, fruity and slightly citrussy young Cognac bottled at 40% and perhaps only two or three years old, to a heavy, rich, powerfully aromatic, intense and very complex cognac bottled at almost 60% and over thirty or forty years of age, the taste spectrum that one different casks from the same distillery can produce is quite amazing.

After this visit - one of the few I made to Cognac (I am much more familiar with Armagnac and whisky as far as the number of visits and assignments is concerned) - I returned to Paris, satisfied with my photos, my notes, and the effects of all those Cognac samples on my palate, but also reassured to know that, although the Cognac category may indeed be dominated by huge multi-national corporations with marketing budgets to rival the GNPs of small countries, and scant interest in actual quality, there are still small, independent distilleries making great produce.

note 1. Christian Guérin no longer works for the Domaine de Chez Maillard: he left this month (May 2018) to become master-blender for Martell, one of the big four multi-national Cognac brands that I referred to rather disparagingly in this article...

When he's not obsessing over heritage varieties of vegetables & herbs, chasing off wild deer or otherwise running around the fields of his mountain farm, he's trying to beat the system, taking photos or trying to better understand cryptocurrencies.

You can find his Steemit introduction here

You can find out more about his farm here: @potager-cerfs