Section 1 – What exactly is the Aperture?

The best way to understand aperture is to think of it as the controls for the pupil of an eye – the wider it gets, the more light it lets in.

Together, the aperture, shutter speed and ISO produce an exposure. The diameter of the aperture changes, allowing more or less light onto the sensor depending on the situation.

More creative uses of different apertures and their consequences are tackled in Section 2 but, when talking about light and exposure, wider apertures allow more light and narrower ones allow less.

Section 2 – How is Aperture measured and changed?

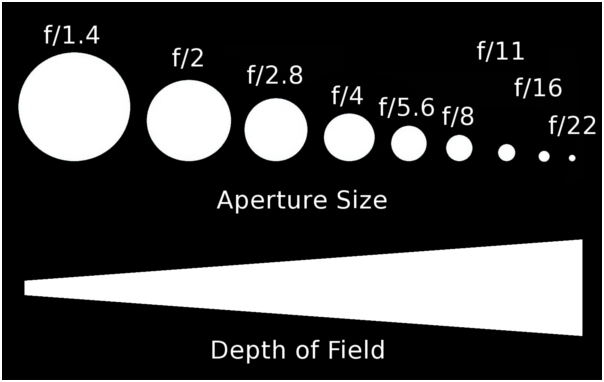

Aperture is measured using something called the f-stop scale. On your camera, you’ll see ‘f/’ followed by a number.

The number denotes how wide the aperture is which, in turn, affects the exposure and depth of field (also tackled below) – the lower the number, the wider the aperture.

This may seem confusing; why a low number for a high aperture? The answer is simple and mathematical, but first you need to know the f-stop scale.

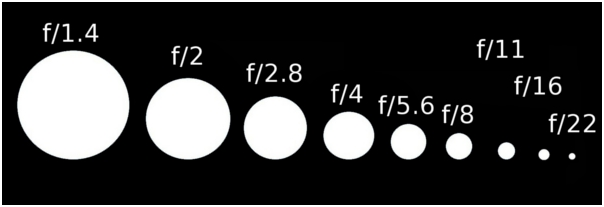

The scale is as follows: f/1.4, f/2, f/2.8, f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/11, f/16, f/22.

The most important thing to know about these numbers is that, from each number to the next, the aperture decreases to half its size, allowing 50% less light through the lens.

This is because the numbers come from the equation used to work out the size of the aperture from the focal length. You’ll notice, on modern day cameras, that there are apertures in between those listed above.

These are 1/3 stops, so between f/2.8 and f/4 for example, you’ll also get f/3.2 and f/3.5. These are just here to increase the control that you have over your settings.

Now things begin to get a little harder. If you get confused, skip to section 3; the most important part has been covered.

Say, for example, you have a 50mm lens with the aperture of f2. To find the width of the aperture, you divide the 50 by the 2, giving you a diameter of 25mm.

You then have to take the radius (half the diameter), times it by itself (giving the radius squared) and times that by pi. The whole equation looks something like this: Area = pi * r².

Here are a couple examples:

A 50mm lens, with the aperture of f/2: 50mm/2 = a lens opening 25mm wide. Half of this is 12.5mm and using the equation above (pi * 12.5mm²) we get an area of 490mm².

A 50mm lens, with the aperture of f/2.8: 50mm/2.8 = a lens opening 17.9mm wide. Half of this is 8.95mm and using the equation above (pi * 8.95mm²) we get an area of 251.6mm².

Now, it doesn’t take a genius to work out that half of 490 less than 251 – this is because the numbers used are rounded to the nearest decimal point. The area of f/2.8 will still be exactly half of f/2.

This is what the aperture scale looks like in reality:

Section 3 – How does the aperture affect the exposure?

The size of a change in aperture correlates with the exposure: the larger the aperture, the more exposed the photo will be. The best way to demonstrate this is by taking a series of photos, keeping everything constant, with the exception of the aperture.

All the images in the slideshow below were taken at ISO 200, 1/400 of a second and without a flash; only the aperture changes throughout.

This set of photos were taken before the recent purchase of my f/1.4 so the photos are in the following order: f/2, f/2.8, f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/11, f/16, f/22. A good way to see the changing size of the aperture is to look at the size of the out of focus white circle at the bottom left of the imag

The main creative effect of aperture isn’t exposure however, but depth of field.

Section 4 – How does aperture effect depth of field?

Now, depth of field can be a big topic – it is a blog post in itself – but for now, I shall summarize it by saying that it is all about the distance at which the subject will stay in focus in front of and behind the main point of focus.

All you really need to know in terms of how depth of field is effected by aperture: the wider the aperture (f/1.4), the shallower the depth of field, and the narrower the aperture (f/22), the deeper the depth of field.

Before I show you a selection of photos taken at different apertures, take a look at the diagram below which helps to explain why this is. If you don’t understand exactly how this works, it doesn’t matter too much; the ‘how’ we’ll talk about another day; for now it’s just important for you to know the effects.

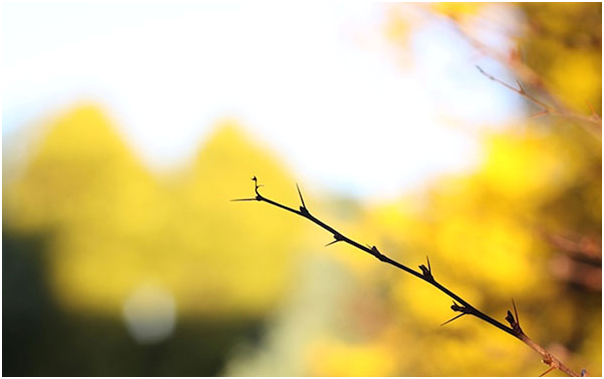

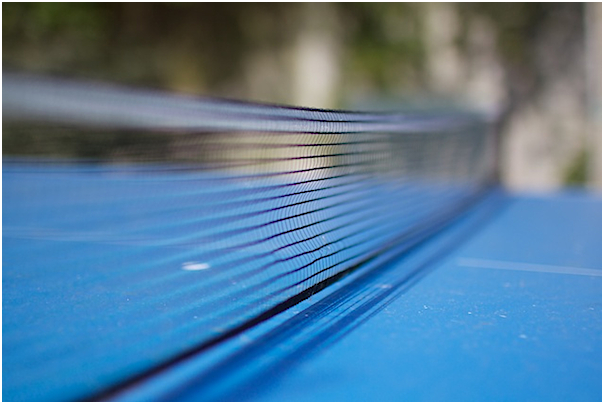

Here is an example of a photo taken at f/1.4. With the subject moving away from the lens, it’s easy to see the effect that the shallow DoF is having on the photo.

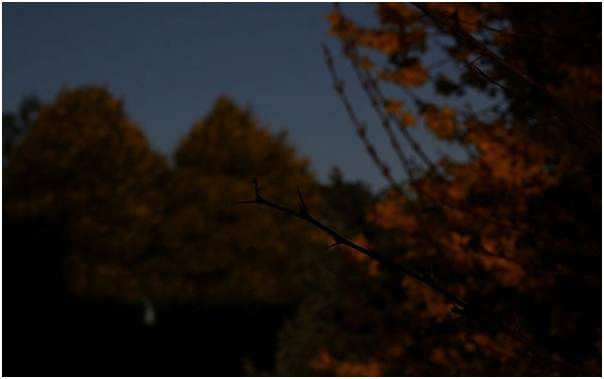

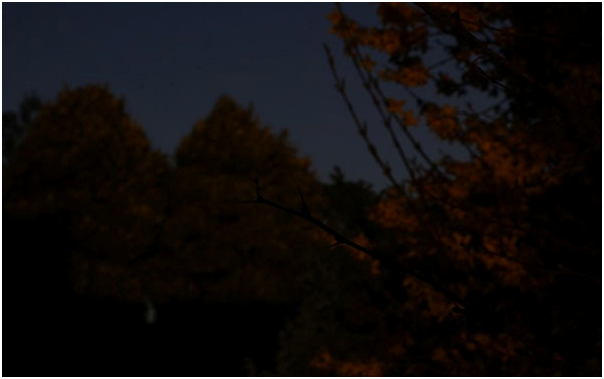

Finally, here’s a selection of photos all taken on aperture priority mode so that the exposure remains constant and the only changing variable is the aperture.

The photos below are in this order: f/2, f/2.8, f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/11, f/16, f/22. Notice how the depth of field increases every time the aperture is decreased

Section 5 – What are the uses for different apertures?

The first thing to note is that there are no rules when it comes to choosing an aperture – it depends greatly on whether you are going for artistic effect or to accurately reproduce a scene in a photo.

To best make these decisions, it helps to have a good knowledge of traditional uses for the apertures listed below.

f/1.4: This is great for shooting in low light, but be careful of the shallow DoF. Best used on shallow subjects or for a soft focus effect.

f/2: This range has much the same uses, but an f/2 can be picked up for a third of the price of an f/1.4.

f/2.8: Still good for low light situations, but allows for more definition in facial features as it has a deeper DoF. Good zoom lenses usually have this as their widest aperture.

f/4: As autofocus can be temperamental, this is the minimum aperture you’d want to use when taking a photo of a person where there is decent lighting – you risk the face going out of focus with wider apertures.

f/5.6: Good for photos of 2 people, not very good in low light conditions though, so best to use a bounce flash.

f/8: This is good for large groups as it will ensure that everyone in the frame remains in focus.

f/11: This is often where your lens will be at its sharpest so it’s great for portraits.

f/16: Shooting in the sun requires a small aperture, making this is a good ‘go to’ point for these conditions.

f/22: Best for landscapes where noticeable detail in the foreground is required.

As I said before, these are only guidelines. Now that you know exactly how the aperture will change a photo, you can experiment yourself and have fun with it!

Collected from : How to Understand Aperture in 5 Simple Steps

by JOSH https://expertphotography.com/how-to-understand-aperture-5-simple-steps/

Great...full of information!!!

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://expertphotography.com/how-to-understand-aperture-5-simple-steps/

Congratulations @shuvosikder! You have received a personal award!

Click on the badge to view your Board of Honor.

Congratulations @shuvosikder! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!