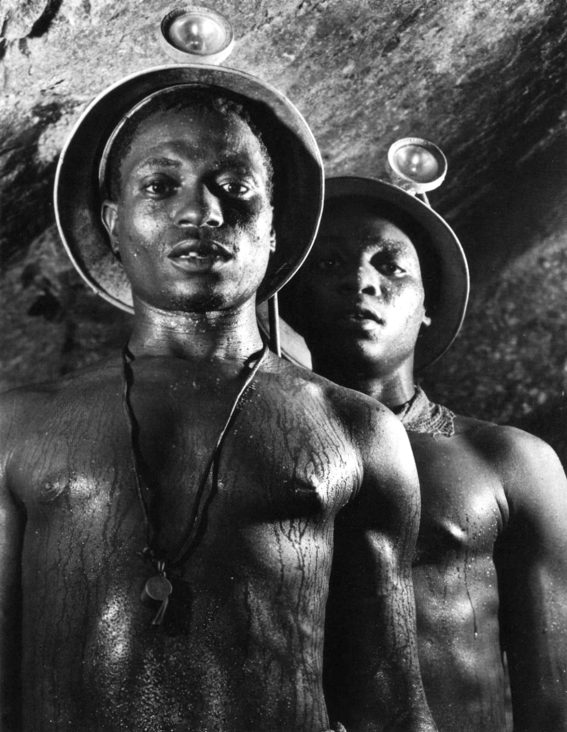

The work of Margaret Bourke-White has become the paradigm of the social and political commitment of American photojournalism. She was initially interested in architectural, industrial and commercial photography. Despite working in an unsightly environment such as the steel industries, thanks to his social skills and good eye, he gained notoriety outside the commercial scope and received in 1930 an important commission for his career thanks to Fortune magazine.

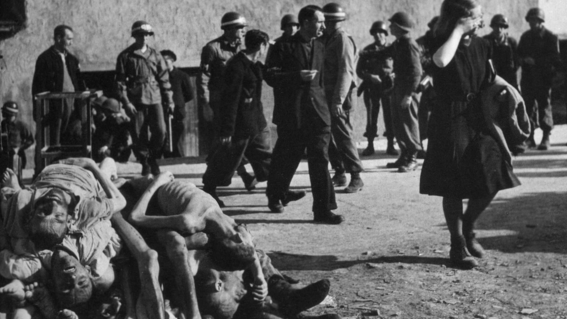

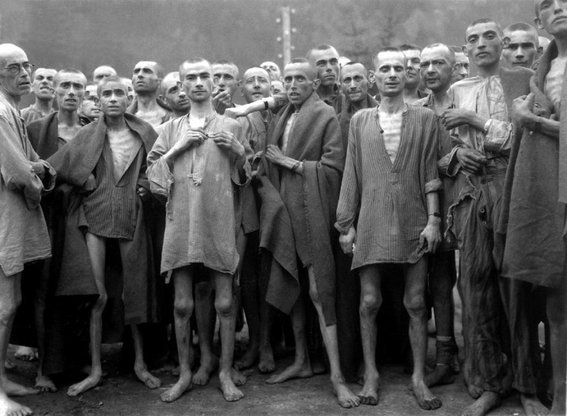

But it was when World War II broke out that he began to develop professionally as a photojournalist. He worked during the war years as a correspondent when portraying the atrocities of the conflict. His moving images of the liberation of the concentration camps had a worldwide impact in terms of perception and consciousness.

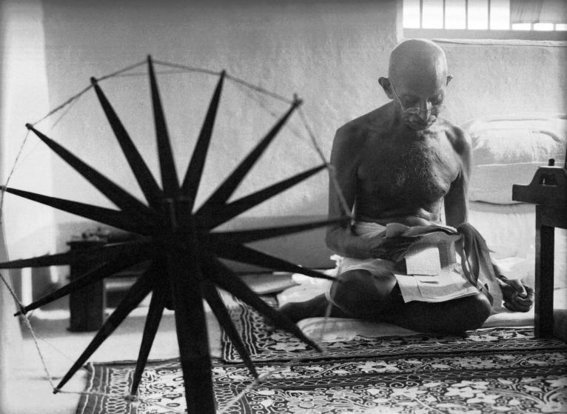

It was in 1946 when he moved to India thanks to a commission of the magazine LIFE to record the reality behind the release of the Hindus, and managed to capture one of his most iconic photographs. The image shows Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi - better known as Mahatma Gandhi - next to one of the most important symbols of Indian independence: the spinning wheel.

When the English deprived of freedom to Gandhi in the prison of Yeravda in Pune, India, from 1932 to 1933, the nationalist leader made his thread with a charka. At first this was only Gandhi's personal way of spending time during his incarceration, but gradually he became a powerful symbol of independence. Gandhi encouraged his countrymen to make their home cloth instead of depending on the products of the English.

When Margaret Bourke-White arrived at the Gandhi compound to write an article about the leaders of India, the charkha was so tied to the identity of Gandhi that his secretary, Pyarelal Nayyar, told Bourke-White that he had to learn the trade before photographing the leader. Bourke-White's image of Gandhi reading the news along with his charkha never appeared in the article for which it was taken. It was after his assassination that the image became the indelible icon we know today.

In addition to the Internet, the Bourke-White legacy can be enjoyed at the Brooklyn Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the New Mexico Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, as well as the public collection of the Library of the United States Congress.