Full Disclosure...

All journalists are biased. They are human beings, after all, with thoughts, feelings, opinions, emotions and experiences that uniquely shape the way in which they perceive the world. To avoid bias in journalism, itself, it is considered ethically (and, in some cases, legally) necessary to acknowledge one's financial associations, et. al. when reporting on a story.

In that spirit, I'd love to give a simple explanation of my political ideology. Unfortunately for me, my ideology doesn't align with the platform of either of this country's two major political parties—neither Democrats', nor Republicans'—as is the case, I suspect, for many (if not most) of you. That said, throughout my life I've always been generally "progressive," which—for my first quarter-century on this planet—had me lean pretty far in favor of Democrats. I supported the late, great Senator John McCain in both his failed primary run for the presidency in 2000 as well as his ultimately unsuccessful 2008 campaign (up until the VP selection, which led to a conversation with one of my closest friends who happens to be from Alaska—after which I decided I was going to vote for Obama because I was so concerned about the possibility of a "President Palin…")

In fact, in 2008, I remember helping a friend of my roommate stuff envelopes in support of Ron Paul's failed 2008 primary run before I supported McCain. I didn't even pay much attention to the Democratic primaries since I'd assumed Clinton was a shoe-in ("Only two years as a Senator? He's not qualified to be President."—me, ca. Feb. 2008) so when I looked up from the Republican primaries to see a black senator from Illinois with the middle name "Hussein" as the presumptive Democratic nominee, I was naturally curious. But the single deciding factor, for me, was the possibility of would-be-President McCain's untimely demise resulting in the ascent of Sarah Palin to the highest office in this nation. (A fatal flaw from a man who is—in this writer's opinion—an otherwise brilliant political strategist: Steve Schmidt. More from him later…)

Paradigm Shift

So I voted for Obama. Twice, because I'm from Michigan, and I can personally guarantee: the trees are not "the right height." 🌳😜

However, the revelations of one Edward Snowden in 2013 lead to my ultimate decision to stop "thinking as a Democrat" (as I felt I'd been doing, while maintaining my official "partisan independence") and, since I certainly didn't align myself socially/culturally with the Republican party, I finally broke free of the shackles of our entrenched duopoly; I started looking at candidates for their own statements, their own voting records, etc. and ignoring that of the party with which they're affiliated. I call this: "voting with your conscience;" whatever your conscience—an extension of your conscious mind, which is hopefully kept reasonably up-to-date with current events, science, etc.—"tells" you is the "right" way to vote, that's how you should vote. Simply put: you should vote for who you think is the best candidate for the job. Different people will have different reasons to vote for different candidates, and that's OK; that's democracy. What's not "democracy" is voting for a candidate you absolutely despise—or, at best, don't feel "especially supportive of"—because you simply have no alternatives.

To be fair, most of the time, you DON'T have any alternative…

We always see those "other" names on the ballot, below the ones we recognize, with party designations that are essentially arbitrary for most voters—unless it's "D" or "R:" the "only two parties whose candidates have any chance of winning." Right? 🤔

Since you don't want to "throw away your vote" (another concept with a fundamentally flawed premise, but we'll save that for another piece…) you want to vote for a candidate that has a chance of winning; you want your vote to mean something. If you simply "throw it away" by voting for an "unelectable" candidate, you didn't contribute meaningfully to the defeat of the candidate you most fear. You may even (gasp!) "help elect" that very candidate by not voting for the next-most-likely-to-win-according-to-poll-X candidate; because your fear of that candidate being elected outweighs your "moral fortitude" to "vote with your conscience," you end up casting a vote for "the lesser of two evils."

Voting for "the lesser of two evils" only guarantees the election of "evil."

This statement is self-evident: voting for "the lesser of two evils" results in—at best—the election of a "lesser evil;" at worst, the election of the "greater evil." Have you ever wondered why we vote this way, instead of voters choosing candidates whom they truly believe can lead the country through whatever problems may arise during that candidate's tenure in office?

Thanks to a September, 2017 study by Katherine M. Gehl and Michael E. Porter, funded by Harvard Business School, as well as a genuine passion to understand the crises facing this nation and have civil conversations about different approaches to solving myriad problems, I've come to the conclusion that this nation not only doesn't "need" political parties as we think of them today—Democrats and Republicans, specifically—but would, in fact, be much better off if their authority immediately ceased to exist. (Something that voters could make happen virtually any time, according to the philosophic idea of "consent of the governed;" in short: "The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government.")

Consider the notion that our system of government was designed to work without political parties by examining the various ways in which parties create unnecessary division and complexity that is not handled by the Constitution, and would not exist if not for partisanship. In fact, the Constitution makes zero references to political parties in any way; I don't believe this was accidental. I believe the founders expected their "living document" to have a hell of a lot more "life" (not to mention the scientific basis for human life, "evolution") after 232 years than a mere 27 Amendments—the first ten of which were passed within two years of its inception, and two of which (#21 and #18) literally cancel each other out, meaning in 230 years we've made 15 changes; one change every 15 1/3 years. The last was proposed September 25, 1789 (yes, that's typed correctly) and ratified May 7, 1992—nearly 27 years ago.

Given our current political climate, I think it's fair to say there are a number of people who don't think any Constitutional Amendment will be ratified ever again. Unless we make some concerted changes, they'll be right.

The Industry of Politics: worse than telcos

While this should be obvious to most economic-minded thinkers, the sheer scale is likely still (and should remain, until it is reigned-in) "alarming." According to figures cited in the aforementioned HBS study, the 2015-2016 election cycle created an ephemeral industry to the tune of $16 billion and nearly 20,000 full-time employees making at least minimum-wage—and that's only at the federal level. Additionally, because of "dark money" sources in politics, the actual figure is likely a few- to several-billion dollars higher than that.

So for $8 billion/year, we must be sourcing the most fantastic, top-notch, brilliant, cream-of-the-crop candidates, right? (You already know that question was facetious. 😉) The United States Presidential Election of 2016 featured the two most disliked candidates ever nominated by either major party. Previously, a candidate would have been deemed "unelectable" with "disapproval" ratings above 50%, yet both Clinton and Trump sported "disapproval" ratings comfortably above 60%.

However, unlike most Americans' beliefs that "Washington is broken," from the perspective of the current Democrat and Republican duopoly Washington is working exactly as intended: creating fear and division among citizens, making it easier to "compartmentalize" and "corral" us into one party or the other. If there's one thing both parties should be afraid of, it's that Americans are starting to get wise to their tactics, sick of their inaction and incompetence, and opening their minds to new ideas.

In the process of weeding ones own mind of entrenched duopolistic thinking, it's important to keep in mind:

- not all "new" ideas are really as "new" as some would like you to believe, and

- the existence of extremism on one end of the left/right polar spectrum does not automatically guarantee (or even encourage) the same on the other.

What is demonstrably true is the fact that both Democrats and Republicans routinely engage in ethically dubious fundraising, voting against the ideology they claim to espouse for the sake of special interests, and creating fake "wedge" issues which—despite not having any business in the national conversation around governing—cut to the core of many peoples' religious/moral views and act as a lightning rod to attract voters to one side or the other out of fear that the "greater evil" will prevail, not necessarily because they support anything in that party's platform. What's worse: while the concept of reasonable government regulation in most industries is acceptable and desired for a majority of Americans, the Politics Industry is made up of those who have little-to-no interest in regulating themselves at all—contrary to their promises to the American people.

The only thing more dangerous than an industry allowed to operate completely without rules or consequences is an industry that makes its own rules—some without consequences—and decides when—or if—they should be enforced.

Problem: The Major Parties Don't Want to Solve Problems

In 2010, President Barack Obama created a bipartisan Presidential Commission on deficit reduction for the purpose of identifying "policies to improve the fiscal situation in the medium term and to achieve fiscal sustainability over the long run." Commonly referred to by the names of its co-chairs Alan Simpson and Erskine Bowles, "Simpson-Bowles" aimed to reduce the federal deficit by almost $4 trillion and reduce debt 60 percent by 2023, among other goals.

Built from a set of assumptions known as the "Plausible Baseline," a scenario closely resembling that of the Congressional Budget Office, the plan proposed roughly $2 in spending cuts to $1 in revenue increases. The report's preamble reads:

The President and the leaders of both parties in both chambers of Congress asked us to address the nation's fiscal challenges in this decade and beyond. We have worked to offer an aggressive, fair, balanced, and bipartisan proposal—a proposal as serious as the problems we face. None of us likes every element of our plan, and each of us had to tolerate provisions we previously or presently oppose in order to reach a principled compromise. We were willing to put our differences aside to forge a plan because our nation will certainly be lost without one.

Because a proposal with so much bipartisan support and promise for future economic security by responsibly reducing spending while making moderate offsets in revenue increases was adopted, the US finally started to see a decline in the national debt and balanced budgets for the first time in a generation. 🙄 Except, not—Simpson-Bowles went nowhere. There was genuine bipartisan support from numerous legislators, but it wasn't enough. Ultimately, neither party would split from its ideology and Simpson-Bowles died a bipartisan death.

Who's to blame for this waste of time and effort, all to have ideology stand in the way of real-world solutions? Democrats and Republicans. President Obama did not show strong support for the Commission's results, and Representative Paul Ryan—who served on the Commission, himself—voted against its resultant legislation. Not enough legislators were willing to speak up, contrary to their party lines, and demand a solution; doing so could risk a primary challenge from their right or left. Yet, neither President Obama nor Representative Ryan nor Congress paid a political price for failing to solve this urgent national problem: Obama won a second term, Ryan became Speaker of the House, and 90 percent of Congress was re-elected.

The duopoly is not accountable for the results of their failed policies, because there is no political competition capable of making them pay a meaningful price.

Politics isn't "Broken;" It's Doing What it was Engineered To Do

[Ed: Before I continue "vilifying" Democrats and Republicans, I should state something obvious: the people that make up the Democrat and Republican parties—those Americans seeking to hold office, specifically—are, according to both recent and not-so-recent history, mostly very good people with good intentions. While I consider myself "anti-partisan"—I believe the nation would be better off without long-standing, powerful political parties—I don't believe it is absolutely necessary to "abolish" political parties. I do believe it is absolutely necessary to abolish the political duopoly that currently exists—but that doesn't have to mean "death" for Democrats or Republicans. They'll just have to adapt to changes in the political climate; namely: demands to serve the public interest rather than create artificial division and legislative gridlock.]

Since the Politics Industry sets and enforces (or not) its own rules and regulations, major parties have evolved to create a large-scale "political industrial complex." Through this industrial complex they have enhanced their power and firmly entrenched their duopoly, using their privileged time behind closed doors to control access to the general election ballot, engage in partisan gerrymandering, and ultimately write the the rules to "control" their own "competition." Among the more egregious examples is the "Hastert Rule," which explicitly puts party interests ahead of those of the public.

The "Hastert Rule" is an informal rule and the Speaker is not bound by it. Dennis Hastert, himself, described the rule as being "kind of a misnomer" as it "never really existed" as a rule. In a nutshell: the Hastert Rule dictates that the Speaker never schedule any floor vote for a bill that does not have majority support within his or her party, regardless of the majority outcome of the body itself. That is: 218 votes are needed to pass a bill in the House. If the minority party has 200 votes and the majority 235, and all of the minority party plus 100 of the majority party agree to vote to pass a piece of legislation, under the Hastert Rule, the Speaker would not allow a vote to take place; a "majority of the majority" does not support the bill. Both Democrat and Republican Speakers have used this "rule" (or not) at various times since the 1990s, though the notion of the "rule" never arose until 2006.

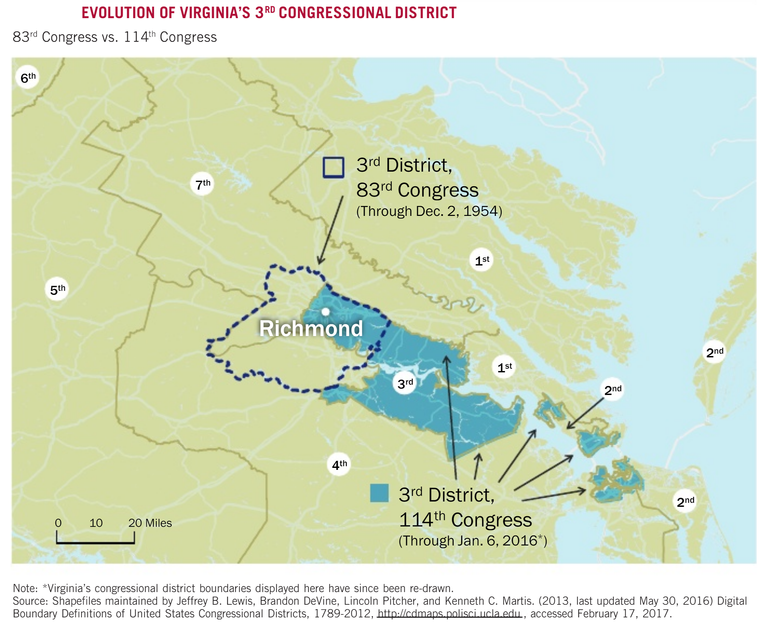

Gerrymandering has been talked about since the dawn of mankind, yet we continue to have districts evolve like VA-03:

Ballot access is an issue that many Americans who have never been involved in political campaigns probably don't really consider [citation needed 🙃], but it is for precisely that reason control over ballot access is one of the more "useful" tools employed by today's duopoly to maintain power.

Fear and Loathing in a Western Democracy

Breaking down the "industry of politics"—including defining the problem(s), identifying desired outcomes, and proposing a path forward to achieve those outcomes—is not an ideal topic for a novice writer to tackle on their second full-blown "piece," given Americans are more polarized than ever—or, at least, that's the prevailing "feeling" of our contemporary era. And there are plenty of different statistics drawn from scientific studies in support of that notion.

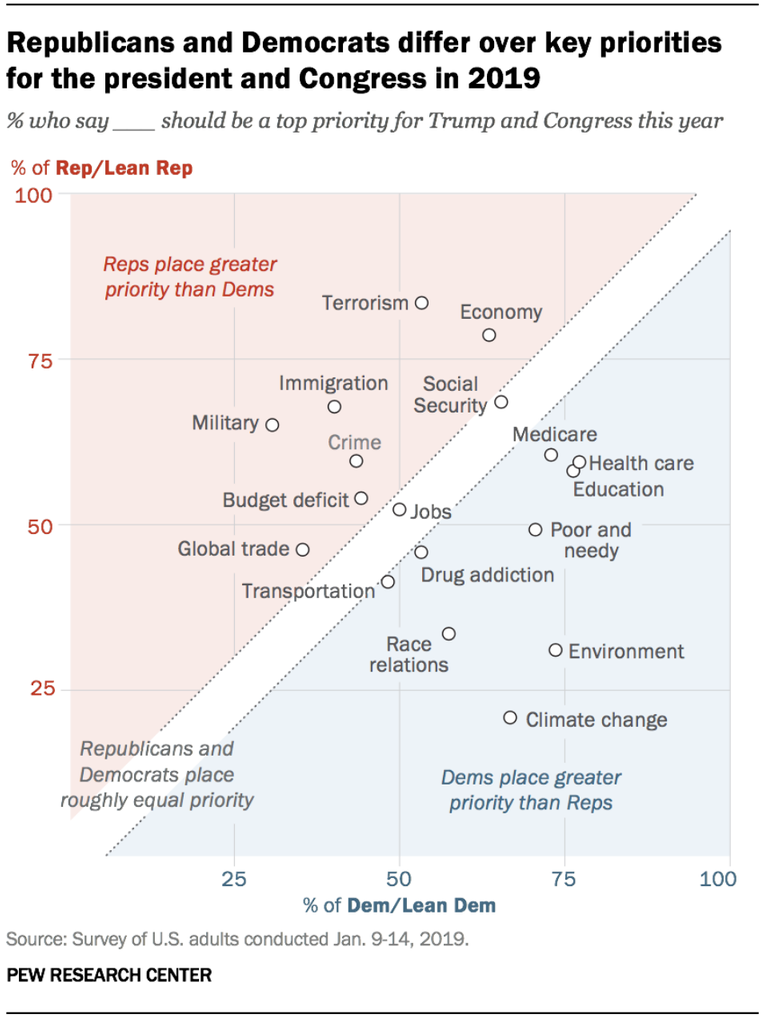

However, when reviewing aforementioned statistics, keep in mind how many questions are asked through a partisan lens. While Democrats and Republicans (including not just elected officials, but voters that consider themselves members of one of the two major parties) tend to strongly agree with members of the same party— with the opposing position taken by the other party—most of the same questions asked of Americans, in general (with no partisan lens) show significantly more agreement among voters. For example, while the figure below attempts to show how divided Democrats and Republicans are regarding specific issues, I think it shows the opposite: given "Climate Change" and "Environment" can easily be lumped together on the Democrat side, and (more loosely, but bear with me) "Terrorism," "Immigration," "Military," and "Crime" all fall under generally the same boat on the Republican side—and the remainder of issues important to Democrats (save for "Race relations") may be directly related to "Jobs," "Global trade," and/or the "Budget deficit"—even this partisan examination of issues important to Americans in 2019 is less "polarized"/"divided" than many would have you believe. 🤷♂️

So if Americans really aren't as polarized as it seems, and that is just an artificial construct created by the duopoly to maintain power, how can we possibly overcome our entrenched, duopolistic thinking and avoid the imminent demise of our nation? Well, in short: we have some work to do. Fortunately, our Constitution was designed to robustly handle even problems as seemingly intractable as this—but it only works when we use it properly.

To be continued...

As Benjamin Franklin left the Constitutional Convention in 1787, he was asked: "What have we got, Doctor—a republic or a monarchy?" Franklin replied: "A republic…if you can keep it."

✅ Enjoy the vote! For more amazing content, please follow @themadcurator for a chance to receive more free votes!

Hello @drinkyouroj! This is a friendly reminder that you have 3000 Partiko Points unclaimed in your Partiko account!

Partiko is a fast and beautiful mobile app for Steem, and it’s the most popular Steem mobile app out there! Download Partiko using the link below and login using SteemConnect to claim your 3000 Partiko points! You can easily convert them into Steem token!

https://partiko.app/referral/partiko

Congratulations @drinkyouroj! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!

Hello drinkyouroj, welcome to Partiko, an amazing community for crypto lovers! Here, you will find cool people to connect with, and interesting articles to read!

You can also earn Partiko Points by engaging with people and bringing new people in. And you can convert them into crypto! How cool is that!

Hopefully you will have a lot of fun using Partiko! And never hesitate to reach out to me when you have questions!

Cheers,

crypto.talk

Creator of Partiko