Political scientists from Harvard and Melbourne University warn that democracy is in a state of deep decline. Even in the richest and most politically stable regions, confidence in democratic institutions is rapidly decreasing, especially among young people.

For a long time, liberal democracy was considered the only correct form of government. Furthermore, Winston Churchill noted:

“At the bottom of all the tributes paid to democracy is the little man, walking into the little booth, with a little pencil, making a little cross on a little bit of paper — no amount of rhetoric or voluminous discussion can possibly diminish the overwhelming importance of that point”.

.jpg)

But these words don’t correlate with the realities of life. An article published by Yasha Munk, Lecturer in Political Theory at Harvard University’s Government Department, and Roberto Stefan Foa, Lecturer in Political Science at the University of Melbourne, states that over the past few decades people have gradually “cooled down” towards democracy, voter turnout has fallen and political party membership has plummeted in virtually all established democracies.

Sunset of democracy

In their article, the political scientists rely on research published by the World Values Survey in 2017, which polled people from nearly 100 countries. The survey studies “changing values and their impact on social and political life”.

The researchers are most concerned that citizens in North America and Western Europe have begun to criticize their political leaders.

“Rather, they have also become more cynical about the value of democracy as a political system, less hopeful that anything they do might influence public policy, and more willing to express support for authoritarian alternatives.”

Source: Yascha Mounk and Roberto Stefan Foa, “The Signs of Deconsolidation”, Journal of Democracy

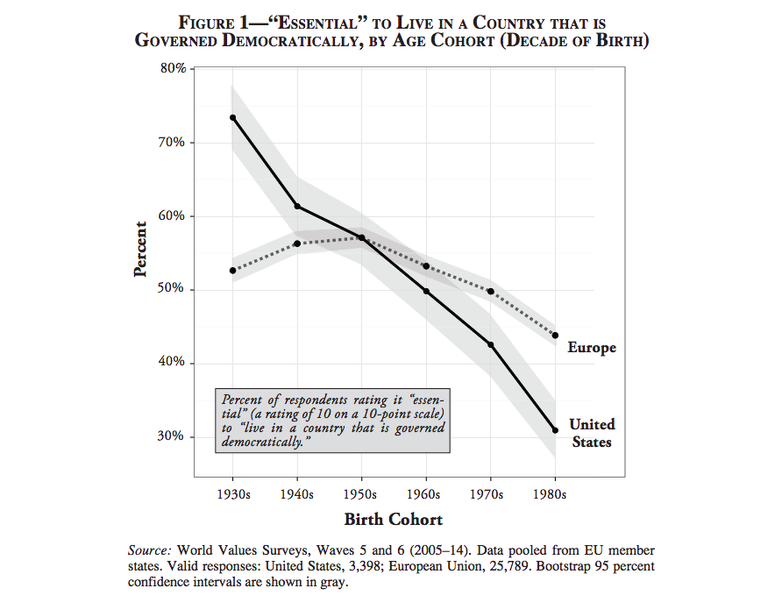

Among respondents of the older generation born before World War II, the concept of democracy is almost sacred. When they were asked to rate, on a scale of 1 to 10, how “essential” it is for them “to live in a democracy”, 72% rated it as 10. The opposite situation can be seen in the responses of millennials (those born since 1980). In the United States only 30% of respondents agree with the tenets of democracy; in Europe the picture is slightly less dramatic.

Source: Yascha Mounk and Roberto Stefan Foa, “The Signs of Deconsolidation”, Journal of Democracy

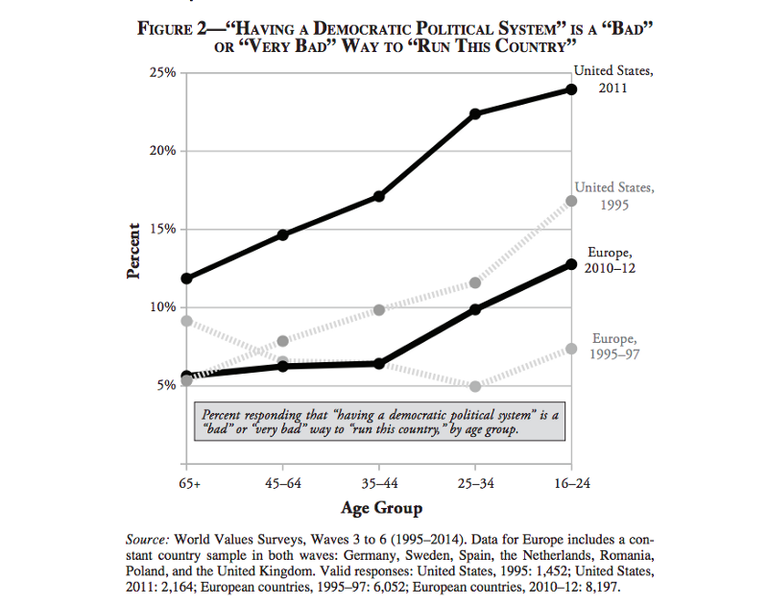

In 1995, 16% of American respondents aged 16-24 said democracy was not the best way to run the country, while in 2011, 24% agreed with this statement. If you look at Figure 2, you can see a distinct change in the anti-democratic attitude of the youth.

New practices

It is difficult to explain exactly why this has occurred, but one assumption is that people feel powerless and “cut off” from the political process, despite having a vote. There is also a lack of trust, with only 16% of Britons saying they have confidence in politicians. As a consequence, turnout has fallen. For the last three general elections in the UK, for example, turnout has been the lowest since the 1940s.

ut this doesn’t mean people aren’t involved in politics. Of course, the loss of confidence led to a reduction in membership of political parties in the US and Europe. At the same time, there has been an increase in the number of protest movements, with people expressing their opinions in online petitions and social media campaigns. For hundreds of thousands of people, the only way to be politically active is via the Internet.

So, instead of people going to elections, maybe it’s time for elections to come to the people and to let them vote online. The crisis of confidence in democratic institutions is obvious. In most democratic countries, the turnout at local elections is pitiful. What harm could it do to try out other systems based on new technology? It would breathe new life into politics, increase engagement, stimulate debate and demonstrate that old democratic practices can be adapted to the digital age.

Use cases for democracy

One of the tools that can help facilitate this is blockchain technology. A blockchain is essentially a decentralized database capable of storing information that is distributed, i.e., not in one place but spread across the computers of all the network members. This technology solves three main problems that democracy and electoral systems face everywhere: the risk of vote rigging, low turnout and the laborious process of counting votes.

Because it’s transparent and secure, blockchain technology can help restore people’s confidence in the political process. After all, corruption still blights elections in countries where democracy is not firmly established. Currently, voters go to a polling station, fill out their ballot papers and place them in ballot boxes for independent officials to count. This method is based on trusting the authorities to collect and count votes honestly. Who can guarantee the honesty and incorruptibility of this approach? Most likely no one.

With blockchain technology, anonymous votes are encrypted into the blockchain and counted and decrypted automatically, without revealing any intermediate results. It’s impossible to interfere or influence the process. It may sound fantastic, but this is exactly how the Polys online voting system works. Moreover, any voter can personally verify that their vote has been accepted, written down in a blockchain and taken into account. Of course, this requires certain skills, but it is possible.

When voters see the result, there will be no room for doubt. And here we turn to the next advantage of online elections based on blockchain technology — an increase in turnout. (Of course, ‘turnout’ may not the best way to describe the process of voting via the Internet, without actually visiting a polling station.)

But perhaps the main advantage of online elections based on blockchain technology is not the increased turnout, and not even the reduction in costs, but a strong interest among today’s youth.

Actual experience

Last December, Polys held a second pilot project at the National Research University Higher School of Economics. The students elected a new ombudsman and Student Council members. It was a large-scale project that involved two cities, 21 local councils, 39 districts, more than 300 candidates and two rounds of voting for the ombudsman. A total of 25,000 people took part in the elections and turnout almost tripled. Elections on such a scale only became possible thanks to the Polys online voting system. The organizers saved 1,120 man-hours and spent just two days organizing and conducting the election and counting the results. This is hard to believe, especially considering the previous year’s election of Student Council members in just one city took months to organize and complete.

But what is even more encouraging, and offers hope, is the fact that after the first pilot project, the HSE students themselves initiated the second large-scale online election on the Polys platform and now have no intention of ever going back to offline voting. In the long term, online elections based on blockchain technology can serve as an incentive to transform the electoral system and enhance the election process, because voters will be able to control it.

That cohort of young people (aged 16-24) that said democracy is not the best way to run countries (see figure 2 above) are the very ones who can revitalize it. After all, young people are open to everything new.

We don’t want to talk about it too loudly, but after the success of the online elections at the Higher School of Economics, Polys received numerous requests from European and American universities. And we, the Polys team, believe that these are just the first small steps of a resurgent interest in democracy.

We invite you to conduct your first online vote now — and we’d really appreciate any feedback.

Originally published at https://polys.me/blog

Wouldn't it be cool if blockchain proved a workaround to Plato (he said Democracy doesn't work, and so far, I agree with him).

Here's a problem, though. Even if, and especially if, blockchain is effective in de-putrifying politics, the entrenched powers will resist implementation. In my country, Canada, our resident clown got elected by running on a platform that included revising the voting system, and the change wasn't anything as good as blockchain. It didn't take long for the proposed proportional representation to get shitcanned, along with many other election promises that he reneged on. It would be an even tougher go in the States.

But you can't win if you don't play; let's go for it!