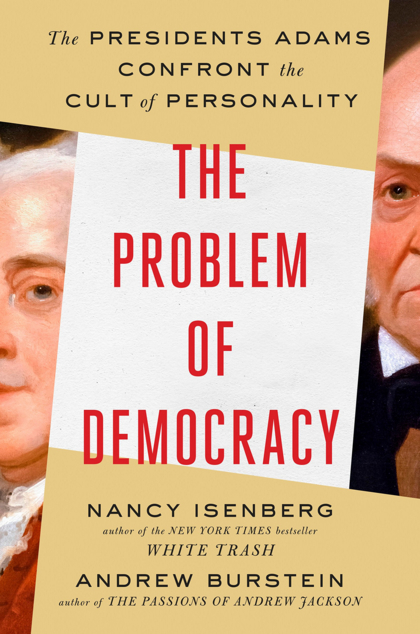

The Problem of Democracy: The Presidents Adams Confront the Cult of Personality is a dual biography of John Adams (1735–1826) and John Quincy Adams (1767–1848) (hereafter JQA, as in the book and many of his own works) by Nancy Isenberg and Andrew Burstein. The book explores their lives in rough chronological order, using excerpts from their letters and books to discuss both their personal struggles and their heterodox political views vis-à-vis the American mainstream.

In the introduction, named “Exordium” after the designation that JQA gave to this part of a book in his Lectures on Rhetoric and Oratory (1810), the authors explain why they wrote the book; partly to set the record straight on the second and sixth U.S. Presidents, and partly to bring light to their critiques of popular democracy and all of the political degeneracy that comes with it. The authors exude a desire for popular democracy to finally happen, but fortunately, they do a fine job of suppressing it until it resurfaces again in the conclusion. Their rejection of the conventions of isolating history into distinct eras with no overlap and of characterizing the period of 1812–24 as the “Era of Good Feelings” is quite refreshing for a work by academic historians. The introduction concludes with a short overview of the history that is told at length in the book proper.

The main part of the book is split into two parts (“Progenitor” and “Inheritor”) of seven chapters each. In the first chapter, “Exemplars,” a brief history of Braintree, later Quincy, Mass., is given alongside a more detailed depiction of John Adams in the 1750s–60s to establish the context into which JQA was born, after his sister Nabby (1765–1813) and before brothers Charles (1770–1800) and Tom (1772–1832). Though most people think of Presidents as being rich, the reader sees that the Adams family was not. The authors detail some of the cases argued by the elder Adams in the 1770s, as well as his pseudonymous writings as “Humphry Ploughjogger.” After a brief speculation on how the Adamses might have sounded when they spoke, the authors discuss the events in Boston that led up to the Revolution, including the impact that the Battle of Bunker Hill had on the Adams family. The role that John Adams' wife Abigail (1744–1818) played in the family is examined at length, from to the education of JQA (called Johnny in his youth) to the differences between her and John on political matters. One finds John making a reactionary traditionalist case for denying female suffrage while Abigail argues a proto-feminist case for equality. Finally, John's writings of the Revolutionary period are shown to contain a pro-democratic sentiment that is absent in his later works.

The next three chapters, “Wanderers,” “Envoys,” and “Exiles,” cover the time that John Adams was in Europe. JQA was with him for most of this time, but later returned home to study at Harvard. One may be surprised to learn that the Adamses had such harrowing experiences in their travels, from an overland journey through the Pyrenees in the winter of 1779–80 to John Adams nearly expiring in 1784 after nearly being shipwrecked while crossing from England to the Netherlands. The authors tell us about the reading materials they had on their journeys, as well as the letters and diary entries they wrote to each other and about other people. These show the elder Adams in particular to be a quick and rather harsh judge of character. In JQA, one sees a sort of young prodigy that is almost not allowed to exist anymore, helping with translations for a diplomatic mission in St. Petersburg, Russia at an age when a modern youth would be a high school freshman.

The third chapter begins with a comparison between the father's and the son's diplomatic careers, which were quite similar in disposition and location. Notably, both were part of negotiations to end a war with Great Britain (the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, respectively). Here, one sees in both Adamses a long-term mentality that democratic politics almost never rewards, with both working to secure American commercial ties; the elder with the Dutch. That John did not see eye-to-eye with Benjamin Franklin is well-known, though perhaps not in the detail described here. Some attention is also given to a rivalry between JQA and Franklin's doubly illegitimate grandson William Temple Franklin. In his appraisal of the marquis de Lafayette, John Adams revealed his distrust of fame and its corruption, especially on the young who are ill-equipped to handle it. One then finds John Adams exhibiting a degree of hubris both for himself and for America, even regarding French involvement in the Revolution as a means of regaining lost pride from the French and Indian War (1754–63).

Read the entire article at ZerothPosition.com

References

- Isenberg, Nancy; Burstein, Andrew (2019). The Problem of Democracy: The Presidents Adams Confront the Cult of Personality. Viking; New York. p. 146.

- Ibid., p. 158.

- Ibid., p. 222.

- Ibid., p. 247.

- Ibid., p. 460.