Just how confident are you in your abilities? Is your performance above average or do you doubt your ability to perform well?

Image source

An overview

We all know the guy at work—a software programmer, say—who boasts about his programming skills and never tires of talking about his achievements. But you know he produces buggy and out-of-spec code and takes forever to finish a project. When his manager gives him a low score in a performance review, he's incredulous and can't believe what he's hearing. “I'm the best programmer in the team! How can you possibly give someone with my talent such a low score?”

And there's the young lady who works away diligently in the corner producing excellent, well-tested and well-documented code that always just works. She's the one you go to when you need some help. But she's almost apologetic about the advice she gives you saying, “This is the way I've done it before but I'm not sure it's right. Perhaps you should check with Fred”—referring to the braggart above. When she gets her high performance score, she's typically very modest about it and thanks the manager as if he's done her a huge favour, and never tells her colleagues about her achievement.

Both of these people suffer—directly or indirectly—from the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Wrong estimations

In general, the Dunning-Kruger effect is a type of cognitive bias in which people of low ability in a particular skill or activity tend to unduly overestimate their abilities, an illusionary superiority. In simple terms, it's people who are too ignorant to know how ignorant they are.

The inverse also applies: unusually competent people tend to underestimate their ability compared to others. This is known as the impostor syndrome. Again, in simple terms, it's a person who says, “I've learned enough about this subject to know what I don't know.”

The Dunning-Kruger effect is named after David Dunning and Justin Kruger of Cornell University. It all started when investigating the cognitive bias in the criminal case of McArthur Wheeler, who robbed banks while his face was covered with lemon juice. Odd as this may seem, he believed this would make it invisible to the surveillance cameras, a belief based on his misunderstanding of the chemical properties of lemon juice as an invisible ink.

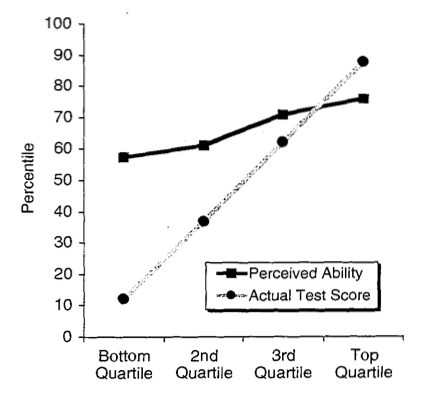

Dunning and Kruger performed hundreds of tests on students on a series of criteria such as humour, grammar and logic. The actual results of these tests were then compared with each student's own estimation of their performance.

Those who scored well on the test were shown, consistently, to underestimate their performance. Since they found the task easy they mistakenly thought that they would also be easy for others. This type of impostor syndrome is mainly found notably in graduate students and high-achieving women—high achievers who fail to recognise their talents as they think that others must be equally good.

On the other hand, those who scored lowest on the test were found to have grossly overestimated their scores, thus displaying the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Here are the findings from the original paper. The worst performers—those in the bottom and second quartile—grossly overestimated their ability (also note how the best performers underestimated it):

Image source

The tests were not based on intelligence but on competence. It's not that the worst performers were necessarily stupid but simply on how well they performed the task.

A little knowledge is a dangerous thing

Examples of the Dunning-Kruger are found widely in public life. Climate denialism is rife with its advocates applying very limited knowledge to a complicated—and incredibly well-studied subject—and use “common sense” to come up with their baseless assertions. Other notable examples are the Answers in Genesis crowd and anti-vaxxers.

Image source

The prime example of the Dunning-Kruger effect is among supporters of Donald Trump (and of course, Trump himself). A recent study carried out by the political scientist Ian Anson at the University of Maryland Baltimore County, it found that those who score low on political knowledge tend to overestimate their expertise—even more when greater emphasis is placed on political affiliation.

This effect may help explain why certain Trump supporters seem to be so easily tricked into believing proven falsehoods when the President delivers what have become known as “alternative facts,” often using language designed to activate partisan identities. Because they lack knowledge but are confident that they do not, they may be less likely than others to actually fact-check the claims that the President makes.

(Psychology Today)

In a recent interview with David Dunning, he emphasised that people who suffer from the Dunning-Kruger effect don't know that they do:

The first rule of the Dunning-Kruger club is you don’t know you’re a member of the Dunning-Kruger club. People miss that.

In essence, he said:

... our brains hide our blind spots from us. And the Dunning-Kruger effect is one example of how: We often feel more confident about a skill or topic than we really should. But at the same time, we’re often unaware of our overconfidence.

This means that everyone is susceptible to the Dunning-Kruger effect. How many times have you come across a well-educated person—an expert in his/her field, and yet flails around with stupid ideas with the same certainty as with his/her main expertise?

So what can we do to help us trust our own self-assessments? How about these three things (from verywell mind):

Keep learning and practising. Instead of assuming you know all there is to know about a subject, keep digging deeper. Once you gain greater knowledge of a topic, the more likely you are to recognize how much there is still to learn. This can combat the tendency to assume you’re an expert, even if you're not.

Ask other people how you're doing. Another effective strategy involves asking others for constructive criticism. While it can sometimes be difficult to hear, such feedback can provide valuable insights into how others perceive your abilities.

Question what you know. Even as you learn more and get feedback, it can be easy to only pay attention to things that confirm what you think you already know. This is an example of another type of psychological bias known as the confirmation bias. In order to minimize this tendency, keep challenging your beliefs and expectations. Seek out information that challenges your ideas.

One of the questions you can ask yourself is how well do you react to positive criticism—an essential determinant of how well you can prevent falling into the Dunning-Kruger trap.

I found this little test quite revealing—try it for yourself:

How Do You React to Constructive Criticism?

References:

verywell mind: What Is the Dunning-Kruger Effect?

Wikipedia: Dunning–Kruger effect

Rational Wiki: Dunning-Kruger effect

An expert on human blind spots gives advice on how to think

Forbes: The Dunning-Kruger Effect Shows Why Some People Think They're Great Even When Their Work Is Terrible

Psychology Today: The Dunning-Kruger Effect May Help Explain Trump's Support

Also posted on Weku, @tim-beck, 2019-02-02