As the global human population continues to grow, develop and change, so too do their health issues. Therefore, it is a continuous challenge for policy makers and stakeholders to assess how to best improve the health of all populations globally.

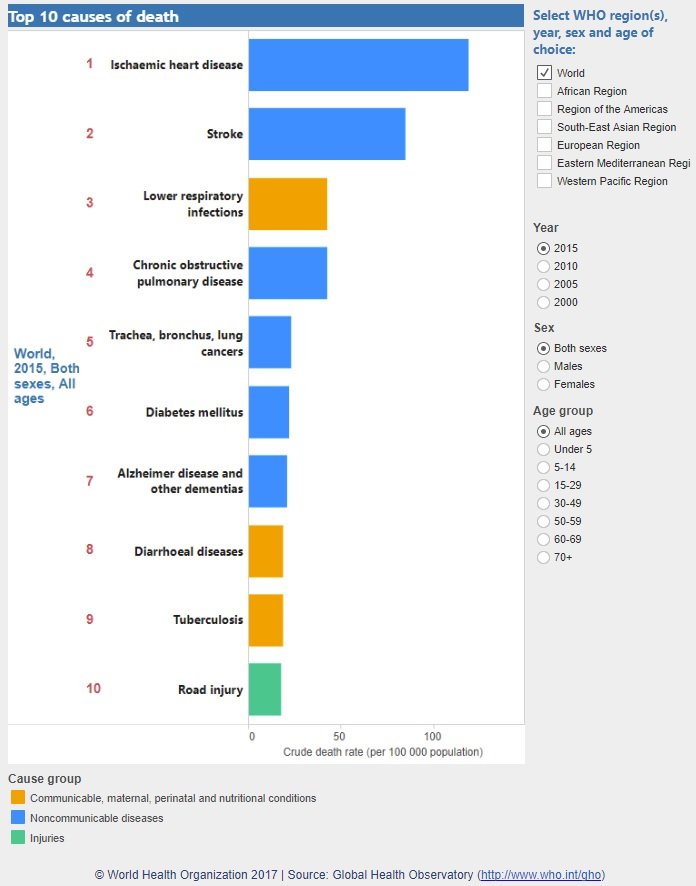

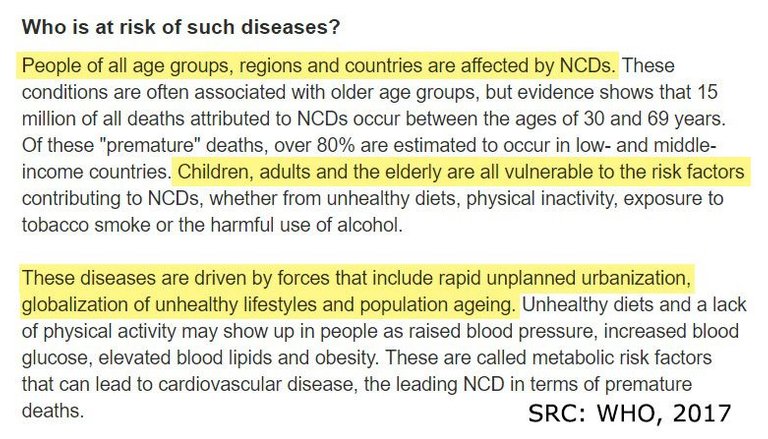

In 2015, the prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCD), also known as chronic diseases, had risen to 70% of all global deaths and qualify as the leading cause of death in the world killing 40 million people every year (WHO, 2017). Tragically, most of these deaths are premature, occurring in people aged between 30 and 69. According to the WHO, 80% of premature heart disease, stroke and diabetes can be prevented, which highlights the urgent need to control this burden on people, health care systems and economies (WHO, 2017).

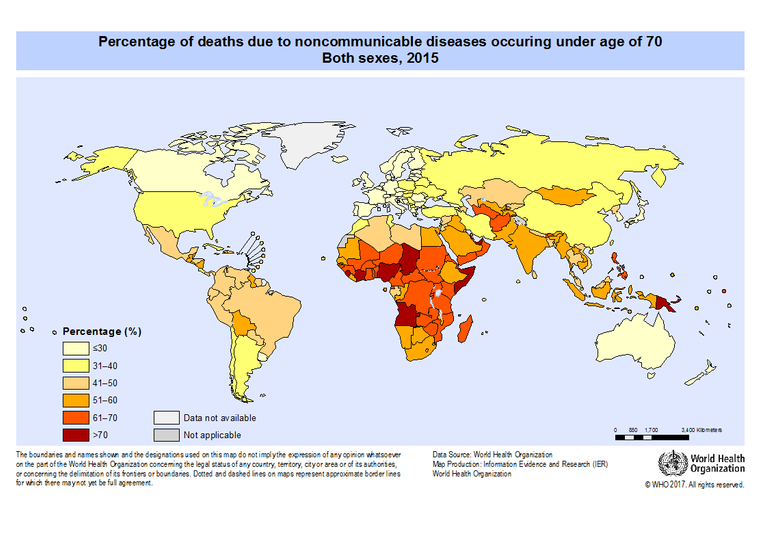

Out of the total deaths caused by NCDs globally during 2015, 82% occurred in low- and middle-income countries. Lower-middle-income countries (LMIC*) have a gross national income (GNI) per capita between $1,006 and $3,955 and low-income countries have a GNI per capita of $1,005 or less (The World Bank, 2017). Thus, they have insufficient capacity to control the burden of NCDs in their communities (Anand & Yusuf, 2011).

*I’ll use LMIC to refer to both low-income and lower-middle-income countries.

Most of these deaths were caused by cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), in which more than 75% occurred in LMICs (WHO, 2017). As at 2015, Ischaemic Heart Disease is the leading cause of death globally, followed by Stroke. Cancers, respiratory diseases and diabetes follow closely behind CVDs.

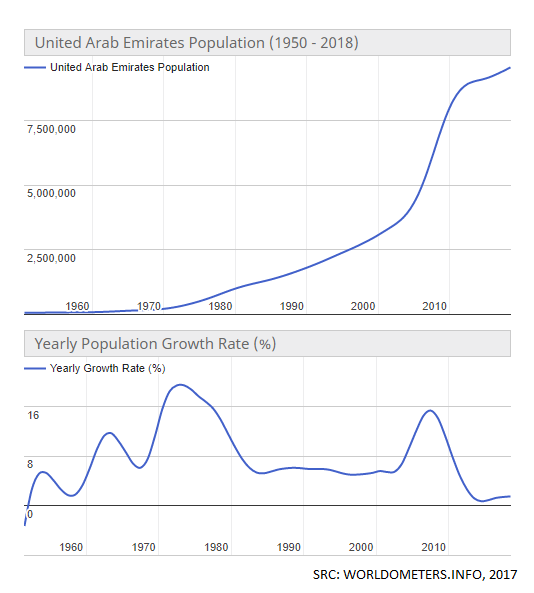

Before I continue, I want to point out that the country with the highest percentage of deaths caused by non-communicable diseases in the world in 2015 was actually a high-income country, the United Arab Emirates, at an astounding 80% (WHO, 2017 & The World Bank, 2017). This proves that there is no singular cause such as an income level that determines the health of a nation’s population. For example, it is important to consider that approximately 90% of their population are immigrants, their rapid population growth, their geographic location (especially their hot climate), and their conservative sociocultural norms (World Population Review, 2017 & Advameg, Inc., 2017).

While the impacts of major modifiable risk factors of NCDs are known across the world, the prevalence of CVDs is not simply determined by risk factors at the individual-level, but also at the population-level with complex and varied causal factors via differing environmental and community influences (Anand & Yusuf, 2011).

Micro-Level Risk Factors of Non-Communicable/Chronic Diseases (WHO, 2017)

Modifiable (behavioural) risk factors of NCDs are:

- Smoking tobacco

- High salt intake

- Drinking alcohol

- Lack of physical activity

Metabolic risk factors of NCDs are:

- High blood pressure

- Overweight/obese

- Hyperglycemia (high blood glucose levels)

- Hyperlipidemia (high blood fat levels)

Macro-Level Analysis

The majority of deaths occurring in working-aged people (aged 30-69) is terribly troubling for LMICs. Families lose their breadwinners and are forced into poverty as their income diminishes and their household costs grow due to healthcare costs. Paying for the medication that would minimise the progression of a chronic disease is not affordable for most people in LMICs. That is, if their healthcare system can afford to supply them with it. In LMICs, there are competing priorities which the healthcare systems have to juggle, such as immunizations and medications to control communicable (or transmittable) diseases like malaria, or high birth rates and associated prenatal, perinatal and postnatal medical care.

While the adults in LMICs today are becoming more incapacitated than ever by NCDs, their children are also extremely disadvantaged in various different aspects with minimal education, malnutrition and stress as they grow into adulthood. Again, the healthcare systems are unable to provide support with most allied health specialist roles such as counselling and psychology that would help. In fact, it’s more likely that populations of LMICs don’t even have access to primary health care services, let alone allied health specialists.

Many children in LMICs don’t progress in education beyond the age of 13 and instead work to help their family survive. This impacts the sociocultural norms as they grow up to start their own family. Mental health issues may stem from a stressful upbringing where domestic violence and food insecurity may be present.

It is reasonable to conclude that a lack of education leads to unhealthy lifestyle choices that are compounding various behavioural (modifiable individual) risk factors for developing chronic diseases. Not knowing the nutritional requirements for their diets coupled with an increase of imported, processed foods high in fat, salt or sugar is a key risk factor. Further, a lack of awareness and education about the health risks of smoking tobacco and drinking alcohol increase this risk.

People living in densely-populated (city) areas might be able to access higher levels of education, but they also have better access to these imported processed foods as well as cigarettes and alcohol compared to those in rural and remote areas. Therefore, it isn’t simply a lack of education that causes the increase in behavioural risk factors, but also the ease of access.

I will conclude my analysis with a focus on the economy. Given that the majority of people who are dying from NCDs are of working age, and their children are unable to progress in education to strengthen the future workforce, it is clear that countries of low- and middle-income levels are in dire need of public health approaches to improve their economic situation. The more people there are who can work, the more products that are able to be produced with the potential for export and trade. A better economy means a better opportunity to grow the healthcare system geographically (extend the range of the health facilities to remote areas) and with an increased healthcare workforce.

The global crisis of chronic diseases as the leading cause of death in the world is predominantly occurring in low- and middle-income countries. It’s a big challenge for many government leaders to turn to their specialist advisers for guidance on establishing the way forward to control the incredible burden on their people, healthcare systems and economies. Though the complexity of the task to reduce the burden of chronic disease in low and middle-income countries may be overwhelming, there is hope.

Remember: 80% of heart disease, stroke and diabetes are preventable!

References:

Anand, S. S., & Yusuf, S. (2011) Stemming the global tsunami of cardiovascular disease. The Lancet, 377(9775), 529–532. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62346-X

Advameg, Inc. (2017) United Arab Emirates, Countries and Their Cultures

The World Bank (2017) World Bank Country and Lending Groups

World Health Organisation (2017) 10 facts on noncommunicable diseases

World Health Organisation (2017) Deaths due to noncommunicable diseases: age-standardized death rate (per 100 000 population) Both sexes 2015

World Health Organisation (2017) Global Health Observatory (GHO) data; Map Gallery

World Health Organisation (2017) Noncommunicable diseases (NCD)

World Health Organisation (2017) Noncommunicable diseases, Fact Sheet

World Health Organisation (2017) Percentage of all NCD deaths occuring under age of 70, 2000-2015: Both sexes, 2015

World Health Organisation (2017) Top 10 causes of death

Worldometers (2017) United Arab Emirates Population

World Population Review (2017) United Arab Emirates Population 2017

Image Source:

All the non cited images are available for Reuse under Creative Commons Licenses from either Pixabay, Pexels, or Wikipedia Commons, or created by me.

@originalworks

To call @OriginalWorks, simply reply to any post with @originalworks or !originalworks in your message!