What makes art “queer?” According to Jennifer Doyle, in her article Queer Wallpaper,

"When we use the word “queer” to describe art or criticism, we are certainly saying something about the importance of sexuality to art—but we are not always ‘outing’ the work of an artist or writer as “gay.” We often use the word “queer” to signal the things that can come with being gay or lesbian, with being a member of a lesbian and gay community, but which are not exactly reducible to sexual identity."

In other words, art is “queer,” if the work and the artist are living outside the conventional or established societal norms, at odds with the mainstream. Queer art and expression does not just have to be made by a LGBT or gender non-conforming artist, nor does the subject have to display scenes that are homoerotic. Art can be considered “queer” art, if outside of the ordinary political or socially accepted systems, or queer things happen where the art is made or a performance is happening. Queerness can be due to how that art happens—is it made in a room covered with aluminum foil, with a team of half-naked models? The art can address subjects that are queer, outside of the sexual realm—makeup, drag queens, idols, or hairdos. One indicator of queer art may be how the art is visible in some contexts and invisible in others, or where you can see the art—is it easily accessible, or do you have to research where to find it? Queer art is art that opens door for others to explore their own queerness, makes art accessible to those who don’t feel they have a place, and, hopefully, is gradually normalizing “extremes.”

Andy Warhol’s art, as a whole, represents and addresses every one of these facets that Doyle would say constitute the label “queer.” His art was done in one of the most welcoming places to all forms of expression, The Factory. Watney explains that Warhol had constructed “a safe space in which everyone and everything is queer.” The Factory, as the name implies, was a place of collaboration on his works, which was not, at the time, considered by critics as the appropriate way for a fine artist to work. In addition to the collective nature of the work and the space, the art made there defied those fine art critics notion of “The Artist”, by being printed over and over, reproduced like mass media. He made art that represented icons of gay or fringe culture, such as Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor—while being bright and glam, it was also drab and static. His art is extremely accessible and visible in some places, while some is hidden in out of the way places—his “popular” art is shown in large museum exhibitions, whereas his prints of male on male sex acts, such as the series “Sex Parts,” is relegated to a dark wall in the back of a gay bar. He supported and promoted those in the social scene around him, he brought them into his “factory,” introduced people with talent to people with money, and opened many doors for the next generations of queer artists to find a place for themselves and their work in the art world.

Thirty-two Soup Cans 1962

Andy Warhol began his life as an outsider, a viewer, to the society around him. Born in 1928, as the child of Slovakian immigrants, he partially learned English from listening to the radio and watching movies and TV shows. In his adolescent and early adult years, he wore unmatched shoes, walked around in his mother’s clothes, and painted his fingernails. For these and other things, he was taunted and tormented by his father and brother and constantly put down by his dominating mother. As Watney says, “Little, queer, mommy’s boy Andrew was predictably teased, bullied, hurt, and humiliated…,” contributing to his inhibitions and lifelong problems with shame, lowered self-image, and feelings of alienation. Society and all of its propaganda, as dispensed through the television, was his only connection to the outside world.

Andy Warhol became a recognized artist before the Stonewall Riots. Though the riots prompted the coming together worldwide of what became the gay liberation movement, which changed the face of gay culture and ushered in a new era of open gay expression, Warhol did not become an activist for the movement. He benefitted from the new liberation, but did not openly display his place in it through his art. Curiously, as Watney says, “Before the emergence of Gay Liberation in the United Kingdom in 1971, Warhol was one of only a handful of cultural exemplars who represented a public face of queerness. He was transparently queer…” So transparent, he had been considered “too queer” for the other homosexuals of the 1950s, who had “accepted a deal that was not available to Warhol. They had, if you will, dehomosexualized themselves, especially in their social role as artists or critics.” He was an outsider to his peers of the period, people who possibly could have understood him best, but he was a still child of their era of thought and non-action, not comfortable with himself in what was becoming a time of openly queer acknowledgement and encouragement.

Though he outwardly represented himself as something out of the ordinary, not of this planet, or “queer,” he separated himself and his work from those who were reacting to the issues surrounding homosexuality, especially that of the AIDS crisis. He was rejecting and refusing to join the politicized queer art movement of the late 80s, a movement which focused on the AIDS epidemic. Even though he was close friends with some of the artists (and victims of AIDS), he kept his distance from them. The ingrained combination of shyness, low self-image, culturally induced shame, fear of disease, and a propensity towards voyeurism is perhaps what stopped him from joining those artists—artists whose work brought the plight of AIDS, and the normalization of gay culture, to the forefront of their work.

Mao 1972

To know Warhol was gay and to be taught the significance of his place in queer art history are two different things. The information comes from different avenues of knowledge transmission. To know Warhol was gay can be as indefinable as having “gaydar,” or the innate feeling of “knowing queer when you see it”, or even word of mouth. To be taught in an academic setting how much he influenced art, in the sense of queerness, one might have to just be at an institute that supports queer and gender studies. A viewer can go to modern museums and not see one word about the influence of gay culture on his work. As Jennifer Doyle says, “You can attend a major museum exhibition on Andy Warhol and never learn that he was gay—never mind that homoerotic and explicitly sexual images animate the entire range of his artistic production.” The museums are not showing this erotic imagery, content to display his more popularized references to the colorful images of the commercial world. They show the soup cans that represent his working class roots, his beloved multiple reiterations of Marilyn Monroe’s glam, or the giant portrait of China’s Chairman Mao. These pieces are comfortable, as they show his connection and seeming assimilation to the majority and what they know. As Doyle states, simply looking at his “Sex Parts” prints, or viewing his movies (or any study of his full career as an artist), would seem to tell a different story—a story that needs to be looked at through the lens of queerness.

.jpg)

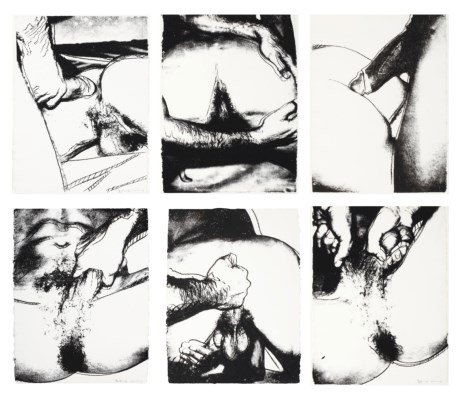

Sex Parts 1978

Both Watney and Doyle are involved personally and professionally with queer culture, which gives them an intimate perspective on Warhol’s work and reception, a perspective that not all share. Watney describes the Lonesome Cowboys opening in London, which he was in attendance, as, “by and large it was a very queer audience.” Yet, he says that the reviews of the film focused on the technical aspects, “the speed of film stock he used, details about the projection speeds, and so on. . . But never sex, let alone queer sex.” Warhol’s film was challenged for being boring, banal, lacking in significance, but not for the overtly gay content. The homosexual aspect was gleaned over, in favor of dissecting his technique—maybe that was the very thing Warhol wanted—to be looked as any artist, not boxed into “queer” or gay.

Sex Parts Series 1978

Doyle describes being able to sit with a Warhol “Sex Parts” print, on display at a local gay bar—a place she is well aware that not all would be comfortable going. The print isn’t highlighted with quality light, or displayed prominently. Somehow in this setting the print is more at home, it is in its intended element, something that would be lost if it were in a museum. Doyle, in contrast, also recounts a time when she was at the media opening for a “survey” of his entire career. She, noticing the lack of wall text for the artwork, attempts to question the museum director about exclusion of any sexual subjects and is, in more or less words, told that the queerness of his art is only there if you see it. She is told that that the museum and exhibition wanted to let the works “speak for themselves.” In a gay bar, the queer aspect is almost impossible to neglect, but in that statement, the museum is able to “whitewash” the entirety of gayness/queerness/uncomfortability by simple omission.

Marilyn x6 1968

Even with all of the proof of his homosexuality, in how he handled himself to the art he made, why is his name not taught to be among the other blatantly “queer” artists of the 1960s through the 80s? How and why has Andy Warhol been “de-gayed” by academics and critics? After Modern Art (1945-2000) by David Hopkins has one line addressing his queerness, stating that his homosexuality was not widely acknowledged until after his death. Hopkins seems to agree with Watney in his saying that Warhol’s “campness was a fundamental survival strategy.” But, it is also possible that those in the field of art history, didn’t know how to address the works at the time—maybe they are still unsure of where Warhol belongs in the place of queer studies. The academic field of queer studies, especially when related to art, is less than a half of a century old. The terms are still being developed, the way we look at the art and the world around still too fresh. Jennifer Doyle says,

"The full discussion of sexuality and art is a very recent development in art history—as central to art history as queer people are (as, for example, artists, critics, collectors, and curators), the subject of sexuality still remains outside the official boundaries of the field. Those writers who do take up sexuality in their work are, in essence, carving out a new field of scholarship."

Those who are able to merge the fields of gender/queer studies and art history are having to name, define, develop and agree on the qualifications of what queer art is. They are having to overthrow the conventions of the critics of the past and step outside and beyond the heteronormative labels and critiques that have already been established. They have to rewrite what is already thought of as history and Andy Warhol’s queer influence is one of those things.

Why is he not celebrated in art history as the one who carved a path for so many queer artists after him? Homosexuality, especially through the 1980s, was considered an obstacle. Warhol did not translate his battles with shame, low self-image, and fear of illness into positive queer art. These were not presented as obstacles for him to overcome and conquer, they were covered and ignored, pushed to the side with glamour and secrets, non-emotion and aloofness, only showing that which was campy and banal. Watney seems to think this is one of the things contributing to the lack of fight from the queer community,

"Perhaps one reason why Warhol has been so comparatively neglected by gay culture critics is the extent to which his work frankly and painfully enacts scenarios of homosexual shame which were largely incompatible with the aesthetic of normative ‘positive images’ that so dominated lesbian and gay Anglophone culture in the seventies and early eighties. He was too tortured and ‘nelly,’ too embarrassing.”

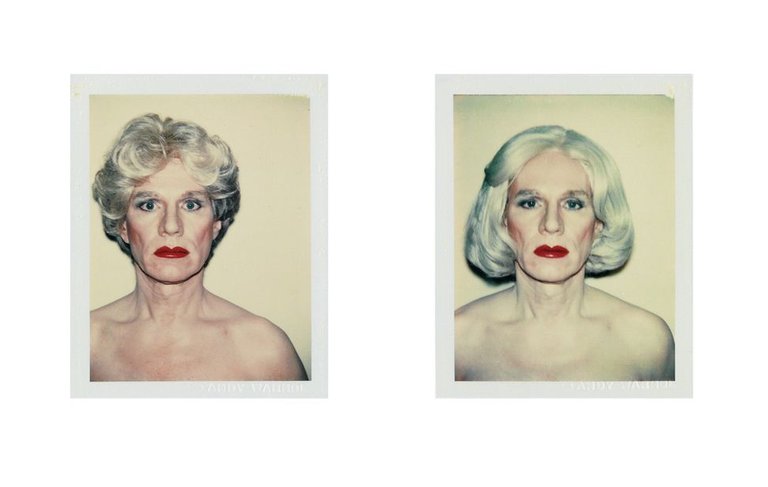

Polaroid Self-Portraits 1981

Did Warhol’s lack of activism for the queer community contribute to his queer erasure? Possibly. In the face of what we think are obstacles, what is better to claim and project?—A positive, strong, secure face for the needs of queer liberation (such as Mapplethorpe or others), or an insecure, campy, boring, passive Warhol, who wouldn’t even answer direct questions with his own thoughts and opinions?

That is the challenge in history. Who do we acknowledge as having represented any place, time, movement, or culture? Who decides? Do we only include that which is easy to dissect, or do we allow the things that challenge us? Warhol does both, his work is big, bright, colorful, gay and it is dark, gritty, banal, queer. Which do we acknowledge? How do art historians and queer critics resolve this seeming impasse? Like Doyle says, “And I remembered: that—the integration of art into life—is just the sort of thing that queer art is all about.” When all the aspects of Andy Warhol are incorporated, looked at through the lens of queer theory, both in print and in the places we view the work, art history (in terms of his work) will be whole.

References

Jennifer Doyle "Queer Wallpaper"

Simon Watney "Queer Andy"

Resteemed to over 15100 followers and 100% upvoted. Thank you for using my service!

Send 0.200 Steem or 0.200 Steem Dollars and the URL in the memo to use the bot.

Read here how the bot from Berlin works.

We are happy to be part of the APPICS bounty program.

APPICS is a new social community based on Steem.

The presale was sold in 26 minutes. The ICO will start soon.

Read here more: https://steemit.com/steemit/@resteem.bot/what-is-appics

@resteem.bot