One evening, nearly 20 years ago now, I sat across from my dad in our living room and explained through tears that I was concerned for his soul. You see, I had recently had a profound spiritual experience and become a follower of Christ after having grown up an atheist, and I was beginning to see the world differently. To be sure, I was young, zealous, and unstudied… but I very quickly possessed an authentic burden for my family members to know and experience what I had come to know and experience. My dad, an atheist at the time, listened patiently and proceeded to systematically dismember my newfound faith with a series of pointed logical arguments, most of which dealing with the problem of pain. I was speechless. I didn’t have a response to his thoughts and observations which he had clearly pondered deeply for decades. Despite feeling totally dejected after our conversation, my faith wasn’t shaken. I don’t know why. The very same questions he asked me then, in 1998, are the ones that plague me now. I find myself daily wrestling with the fundamental questions concerning pain, suffering, and evil – and all the attending philosophical offshoots – and ending up with more questions than answers after each struggle.

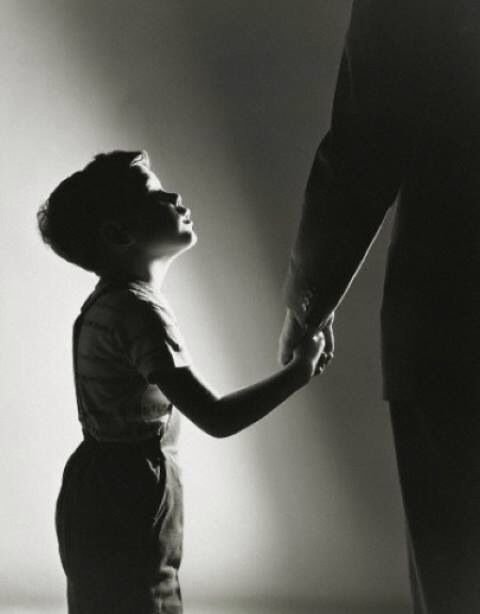

I’m learning, however, there is a unique beauty and even blessing in the (often extreme!) tension. Though much remains that I do not understand, I have come to learn a few things that I would like to pass on here concerning the problem of pain. These insights are the fruit of a system of thought that is deeply rooted in the Christian faith and Biblical scriptures, in which, I believe, exists a cohesive framework for perceiving reality and understanding the human condition. And while an academic approach to the problem of pain is noble and necessary at times, I have found that metaphors and anecdotes often open a back door to the chambers of wisdom and knowledge. After all, according to CS Lewis, though “reason is the natural organ of truth, …imagination is the organ of meaning.” Therefore, this post will explore at least one aspect of pain through the lens of a father’s relationship to his son.

Several years ago, when my oldest son, Aidan, was about 18 months old, my wife asked me to take him outside to play while she tended to our son, Paxton, who we had just brought home from the hospital. We lived on a piece of property that sat up about 7 feet above street level, which meant that our driveway was steeply inclined near the road. Aidan was running around aimlessly, as toddlers are wont to do, and he began to stray toward the end of the driveway. As he ran downhill, he began to lose control as his big toddler head tipped his center of balance downhill. Most people instinctively put their hands out to break their fall when they trip, but Aidan as Aidan fell, he flung his arms back like he expected to take flight at the last moment and avoid the impending impact. I couldn’t exactly see it from where I stood, but I heard the sound of bone scraping and breaking on concrete. I ran up as he rolled over to see that he had somehow landed on his mouth, and in particular his front tooth. His momentum and weight, along with the downhill angle and the concrete, combined to provide enough force to shear his tooth up into the gum. Through the blood I could see tooth fragments on his lip and tongue. I scooped him up and carried him in the house, trying at the last moment to replace my panic with a look of calm, as if this sort of thing happened regularly, so as to not completely freak out my wife! “Hey, sweetheart, Aidan had a fall and scraped up his mouth a bit. No big deal… I’ll get it taken care of.” You know how that goes. “Oh, and he might have fractured his tooth and maybe even his jaw.” As if the blood and screaming hadn’t already given us away.

At any rate, I got on the phone with a friend of mine who is a dentist in another city and he affirmed that we were going to need to see a surgeon to get the remaining shard of tooth and root extracted so that it wouldn’t get infected, and to make sure that no additional bones were broken. I contacted a local pediatric oral surgeon and we scheduled a time to meet. She ensured me over the phone that I didn’t need to rush him to the ER, but that we didn’t want to wait too long to stave off the risk of infection. So we scheduled an appointment for some time in the next couple of days. In the meantime, I got him cleaned up and after some ice and children’s Tylenol, he returned to a somewhat normal state for an 18-month-old.

After a few days elapsed, we took him to his appointment where the surgeon informed us that a simple procedure to remove the remaining tooth fragment and root was all that was needed, and that no further damage to the bone structure had been done. She explained that we had two options: one that would fully sedate him, and another that just used a local to numb the pain. She said even though he would be awake if we chose the second option, he wouldn’t feel much and probably wouldn’t remember the whole ordeal in the end, though he certainly wouldn’t like it in the moment. Since we were paying out of pocket and the local anesthetic was cheaper by orders of magnitude, we went with that option, scheduling the procedure for a day the following week.

At that first visit to assess the damage

When that day rolled around, I showed up at the surgeon’s office with an unsuspecting toddler in tow. I filled out and signed the paperwork and then sat waiting to be called while Aidan played with the bead maze and flipped through books that he held upside down. A nurse came out with a syringe full of medicine that she gave to Aidan to make him drowsy. After a few more minutes, another nurse directed us to smaller room with a TV and a sofa where we watched Pixar’s Cars until the medicine took effect. Aidan fell asleep on my chest and when the next nurse who poked her head in saw he was asleep, she smiled and said it was time to bring him back to the operating room.

I carried his small limp body into a sterile surgical room and laid him on the bed in the middle which was surrounded by a small team of waiting nurses and a masked oral surgeon. The room had been darkened, accentuating the brightly lit bed, where my son was groggily becoming aware of his new circumstances. The doctor informed me that he would soon give Aidan a shot of Novocain to locally deaden the gums around where he would be extracting the tooth, and that when he did, Aidan would likely wake up and not be thrilled about the pain in his mouth. He told me that from there they would quickly restrain him and pull out the tooth fragment with the plyers, but that they may need my help holding him down since his head had to be still to prevent further aggravation.

Sure enough, as soon as they stuck the needle in his gums, it was like someone lit a fire in his mouth and he was instantly fully awake and in a panic. A nurse held his legs, another his head. The doctor leaned over his mouth with the plyers but had to stop to ask for my help. As Aidan screamed and thrashed, the doctor asked if I would lay across his chest and hold down his arms. I obediently stretched my body diagonally across the table to where my chest was on his chest and I held down his arms with mine. I kept my feet on the floor so as not to crush him with my weight. I was shocked at his strength as he arched his back and kicked. I wondered if baby Samson had been as hostile. The angle placed my face about eight inches from his, and as the doctor brought the plyers close to his mouth, Aidan’s look changed from one of terror to one of accusation.

At 18 months old, he couldn’t really say much, but what he lacked in his ability to communicate with his mouth, he made up for with his eyes. He looked at me in such a way as to say, “I knew it… you’re one of them! Traitor! I thought you were for me, that you loved me, but I was wrong. You don’t care about me, you don’t care that I’m in pain!” In response, I leaned in a little closer and began to whisper, “I’m here buddy! I love you and you’re going to be ok. I know you don’t understand, but we have to go through this. I have a perspective you don’t have. If we don’t get the tooth out now, it’s going to get infected and cause you even greater pain down the road. Trust me. I’m with you in this. I love you. You’re gonna be ok!”

As I attempted to comfort my son with those words, the doctor was able to reach in with the plyers, grab hold of the tooth, and pull it free with relative ease. There was a little blood which was quickly tended to and Aidan began to calm down. Once he was given a sucker, you wouldn’t have known he had been screaming for his life just a few moments earlier. All was right with the world once again. He pranced out of the operating room like a little boy who had just woken up on Christmas morning… probably an effect of the drugs and the sugar.

Not long after the tooth extraction

It wasn’t until weeks later that I began to see that whole experience through a metaphorical lens as it concerns the character of God. Throughout that particular series of events, I maintained a perspective as an adult that Aidan simply didn’t have. My age and experience enabled me to see the world differently than Aidan considering his relative youth. I knew that he had a problem that, had it been left unattended to, would have most certainly caused him greater injury later in life. As a result, I was willing to subject him to a little pain now to avoid significant pain later. What was required of him throughout our process was a simple trust in my understanding of how the world works, along with my beneficence and care regarding his well-being. His faith in my favorable disposition toward him could have tempered his anxiety. Would it have lessened the pain? No. Pain is pain. But it would have enabled me to comfort him and encourage him of a brighter future devoid of the tooth fragment. Vision gives pain purpose. I stood tall enough to see over the fence of hardship and relay a message of hope to him who lacked the stature and maturity to see what lay ahead. I needed him to look at me instead of his pain.

Easier said than done, I know. But all of this is true as it relates to our position in God’s family. He stands tall enough to see over the fence of chronic illness, joblessness, premature death, evil intent, deprivation, loneliness, betrayal, and more. He sees beyond and relays to us a message of hope. He asks that we look to him instead of our trial, and to look with eyes of trust and not accusation. To trust that his disposition toward us is one of favor and not of contempt. And that he possesses the requisite wisdom to ensure that all things really do work together for the good of those who love him and have been called according to his purpose. He invites us to lean in and to hear him whisper, “I’m here buddy! I love you and you’re going to be ok. I know you don’t understand, but we have to go through with this. I have a perspective you don’t have. If we don’t deal with this issue now, it’s going to fester inside of you and cause you even greater pain down the road. Trust me. I’m with you in this. I love you. You’re gonna be ok!”

Now, for the Christian, we can be sure of this hope because of God’s victory over death itself. It’s true, many of us will die in the midst of our pain, and often with unanswered questions. But the struggle does not end in death! Resurrection life awaits those who put their trust in Jesus Christ… a stunning reversal of the entropic decay that defines the present state of our world. That promise makes hope possible despite our suffering, for to me, to live is Christ and to die is gain! For if I am to go on living in the body, this will mean fruitful labor for me. Yet what shall I choose? I do not know! I am torn between the two. I desire to depart and be with Christ, which is better by far, but it is more necessary for the sake of others that I remain in the body. This has been the mantra of Christ followers beginning with Jesus himself in the garden and echoing down the halls of history – through the epistles to the modern day killing fields. And what could compel such surrender but a deep trust in God’s ability and commitment to his followers that, indeed, all things work together for good, even when it is the Lord himself who does the restraining.