Scientists have been able to achieve historical development through the development of human female eggs in the laboratory, with the possibility of developing into fertilized embryos in the process is the first of its kind.

Scientists have replicated this process, where egg cells can mature outside the human body, using strips of ovarian tissue, which can provide advanced treatments for fertility in the future, and gives hope again to women who lost their fertility, and do not respond to artificial insemination.

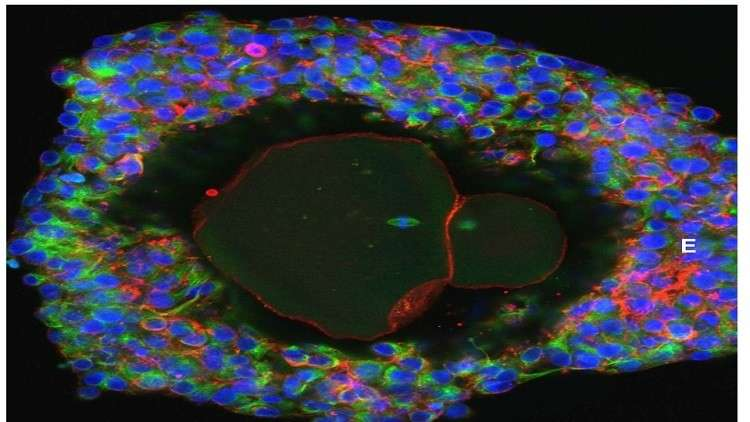

Women are born with millions of immature eggs in the follicle cells within the ovary, which are very sensitive to hormone levels and other environmental factors at each stage of growth, so the University of Edinburgh team replicated these conditions, in collaboration with medical experts.

The latest developments, published in the journal Molecular Human Reproduction, included ovarian tissue extracted from 10 women aged 25 to 39 who underwent cesarean delivery.

The ovarian tissue biopsy was first examined in order to remove any follicles that had already begun the process of maturation, before the growth process began. When the follicles ripened, the eggs were placed under "mild pressure" in preparation for the final stage of growth.

"If we can prove that these eggs are normal and can form embryos, there will be many applications for treatment in the future," said Professor Evelyn Teller, lead author of the study from the Reproductive Health Resource Center at the University of Edinburgh.

While the cultivated eggs are in the final stage of maturity, it is unclear whether they can form a healthy embryo. She explained that there is a lot of organizational and moral work, before the application of fertilization.

"Scientific breakthrough" can provide a solution for young girls with cancer, in particular, who have very few options in maintaining fertility before chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Ovarian tissue is now stored, hoping to grow again when little fertility is restored.

Theoretically, the developed process can be applied to postmenopausal women, although it will be difficult to obtain a piece of ovary, which contains enough oocyte cells.

The study marks the culmination of 30 years of international cooperation, which in the past has shown the details of artificial insemination "from start to finish" in animals, where ovarian tissue samples are more abundant. Many researchers, including Professor Telfer, have completed parts of the maturation process.

Independent experts agreed that applying the treatment developed in fertility clinics would take several years.