Not A Drill: Rosendale Mayor’s “April Fool’s Prank” Dissolved Village, for Real & Forever

“Now hear me when I tell you that my story’s really true; I want everyone to listen and believe. It's about some silly people from a long time ago; and all the things the neighbors didn't know…” – Frank Zappa, 1968

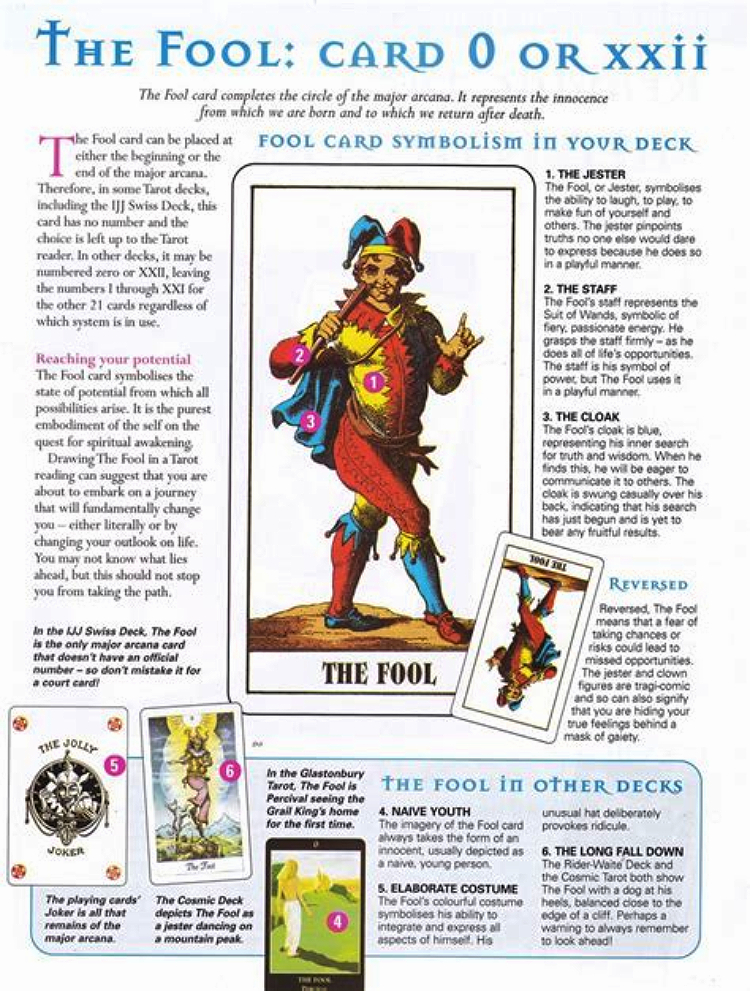

Normally, for the April Fool’s edition of a publication, the author has a rare opportunity to pull the reader’s leg, spinning a farfetched fictional yarn, in honor of that ancient tradition, where pranks are played on the 32nd day of March.

Sadly, this isn’t one of those tall tales. It really happened; in Rosendale, of course - a mythical place renowned for perpetual folly, especially bizarre acts committed by elected public officials. Today, for the first time ever, we are publishing a true misadventure regarding the 1978 dissolution of Rosendale Village.

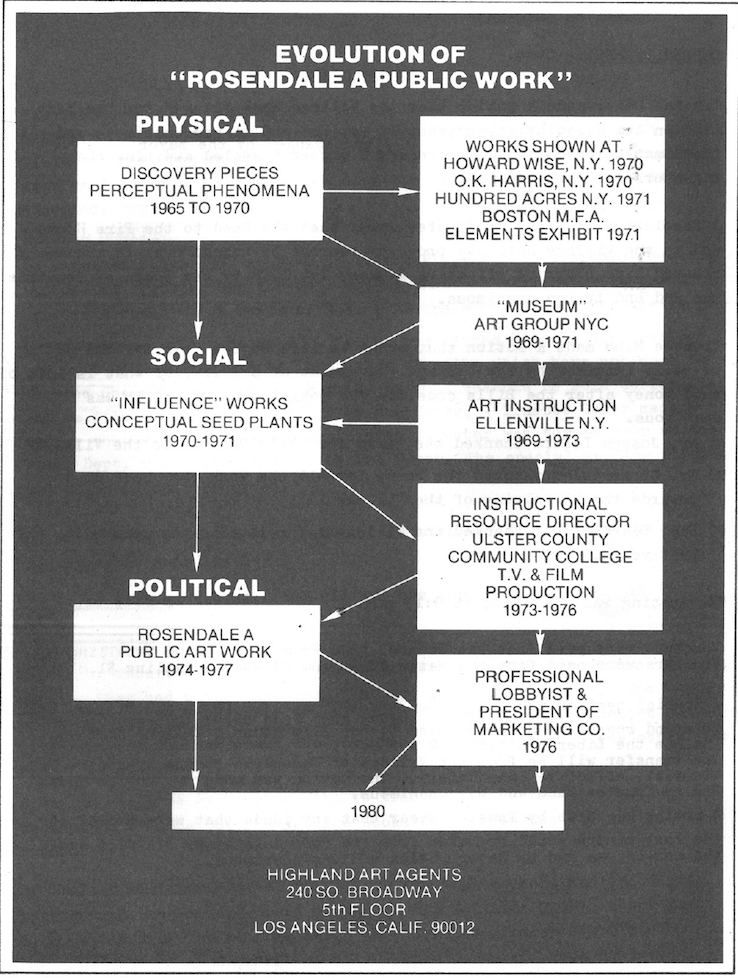

With only 500 words to tell a short version of this account, I’ll have to save more of the insane details for a longer version, in some upcoming future edition of this newspaper. That would include an actual extended interview with Raivo Puusemp, a former adjunct at the local community college, who got himself elected as Mayor of Rosendale Village during the mid 1970s, and erased the municipality as an “art project,” unbeknownst to his own constituents.

Mr. Puusemp later released his “term paper,” explaining in detail his nefarious deed, including how he managed to convince the inhabitants to go along with his hairbrained scheme, and why it was “art.” Citing Marcel Duchamp’s 1957 lecture titled “The Creative Act.” Puusemp invoked the Dada master’s so-called coefficient of art, defined as “an arithmetical relation between the unexpressed but intended and the unintentionally expressed.”

Following his act of civic vandalism, Puusemp's political career became self-eliminated; thus our unemployed mayor migrated with his family to Utah, quit his original calling(s), and instead launched a ski business. The erstwhile mayor barely looked back, to witness the organizational carnage left in his wake.

Residents of Rosendale had no clue as to Puusemp’s true motives; he had convinced the public that dissolution was necessary in order to cut taxes, and eliminate redundancy in government. The Main Street business hamlet became absorbed into the surrounding township, also named “Rosendale.”

According to the late Dietrich Werner, a local historian, village voters wound up paying more for garbage pickup fees, a former village service, than all their old municipal tax expenses combined. A hole was also created in the zoning map, which persisted for two more decades, known only to future officials, who regularly abused that mistake, as a weapon against their enemies.

The awful truth is stranger than fiction! Puusemp’s ridiculous actions, entitled “Beyond Art – Dissolution of Rosendale, 1975–1976,” is a 30-page compendium (presented afterward, at an exhibition in Ellenville), consisting mostly of press clippings discussing Rosendale’s village dissolution. Only much later, during the 1980s, was this material actually published. Read it here: http://rosendale.info/special/puusemp.pdf

Notes:

Raivo Puusemp, Curriculum Vitae: https://makinguse.artmuseum.pl/en/raivo-puusemp

History of April Fool's Day: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/April_Fools%27_Day

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Type Cultural, Western

Significance Practical jokes, pranks

Observances Comedy

Date 1 April

Next time 1 April 2023

Frequency Annual

April Fools' Day or All Fools' Day[1] is an annual custom on 1 April consisting of practical jokes and hoaxes. Jokesters often expose their actions by shouting "April Fools!" at the recipient. Mass media can be involved with these pranks, which may be revealed as such the following day. The custom of setting aside a day for playing harmless pranks upon one's neighbour has been relatively common in the world historically.[2]

Origins

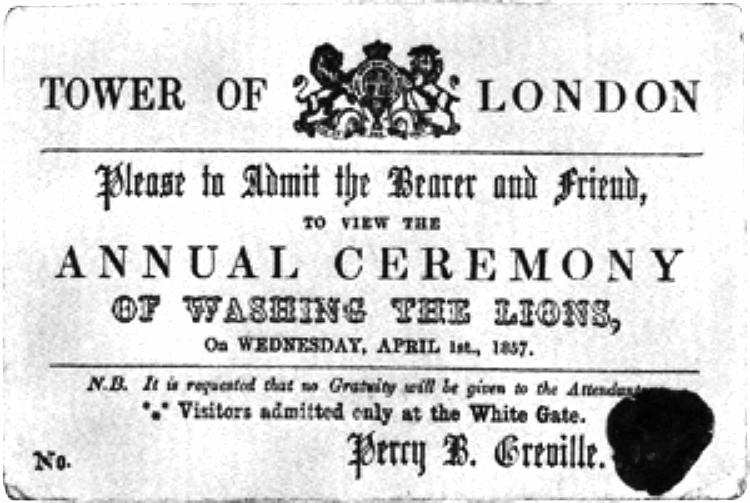

An 1857 ticket to "Washing the Lions" at the Tower of London in London. No such event ever took place.

Although the origins of April Fools’ is unknown, there are many theories surrounding it.

A disputed association between 1 April and foolishness is in Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales (1392).[3] In the "Nun's Priest's Tale", a vain cock Chauntecleer is tricked by a fox on "Since March began thirty days and two,"[4][5] i.e. 32 days since March began, which is 1 April.[6] However, it is not clear that Chaucer was referencing 1 April since the text of the "Nun's Priest's Tale" also states that the story takes place on the day when the sun is "in the sign of Taurus had y-rune Twenty degrees and one," which would not be 1 April. Modern scholars believe that there is a copying error in the extant manuscripts and that Chaucer actually wrote, "Syn March was gon".[7] If so, the passage would have originally meant 32 days after March, i.e. 2 May,[8] the anniversary of the engagement of King Richard II of England to Anne of Bohemia, which took place in 1381.

In 1508, French poet Eloy d'Amerval referred to a poisson d'avril (April fool, literally "April's fish"), possibly the first reference to the celebration in France.[9] Some historians suggest that April Fools' originated because, in the Middle Ages, New Year's Day was celebrated on 25 March in most European towns,[10] with a holiday that in some areas of France, specifically, ended on 1 April,[11][12] and those who celebrated New Year's Eve on 1 January made fun of those who celebrated on other dates by the invention of April Fools' Day.[13] The use of 1 January as New Year's Day became common in France only in the mid-16th century,[8] and that date was not adopted officially until 1564, by the Edict of Roussillon, as called for during the Council of Trent in 1563.[14] However, there are issues with this theory because there is an unambiguous reference to April Fools' Day in a 1561 poem by Flemish poet Eduard de Dene of a nobleman who sends his servants on foolish errands on 1 April, predating the change.[8] April Fools' Day was also an established tradition in Great Britain before 1 January was established as the start of the calendar year.[15][16]

In the Netherlands, the origin of April Fools' Day is often attributed to the Dutch victory in 1572 in the Capture of Brielle, where the Spanish Duke Álvarez de Toledo was defeated. "Op 1 april verloor Alva zijn bril" is a Dutch proverb, which can be translated as: "On the first of April, Alva lost his glasses". In this case, "bril" ("glasses" in Dutch) serves as a homonym for Brielle (the town where it happened). This theory, however, provides no explanation for the international celebration of April Fools' Day.

In 1686, John Aubrey referred to the celebration as "Fooles holy day", the first British reference.[8] On 1 April 1698, several people were tricked into going to the Tower of London to "see the Lions washed".[8]

Although no biblical scholar or historian is known to have mentioned a relationship, some have expressed the belief that the origins of April Fools' Day may go back to the Genesis flood narrative. In a 1908 edition of the Harper's Weekly cartoonist Bertha R. McDonald wrote:

Authorities gravely back with it to the time of Noah and the ark. The London Public Advertiser of March 13, 1769, printed: "The mistake of Noah sending the dove out of the ark before the water had abated, on the first day of April, and to perpetuate the memory of this deliverance it was thought proper, whoever forgot so remarkable a circumstance, to punish them by sending them upon some sleeveless errand similar to that ineffectual message upon which the bird was sent by the patriarch".[2]

The Fool On The Hill (Remastered 2009) -

Daily Eagle News

http://dailyeagle.news

Established July 4, 2019