Inquiry into the nature of interval relationships usually leads us on a direct path through the western diatonic or twelve-tone chromatic foundations of familiarity. Although this discussion will turn to our perceptions of the more common interval relationships

through time, we have a need to understand that these particular intervals are a product of artistic invention and not naturally occurring formations of scales and harmonic tissue. Music cannot, and does not rest solely upon unalterable natural laws.

In addressing the melodies of song we find that their alterations of pitch take place by intervals and not by the continuous transition of notes in a scale. "The musical scale is as it were the divided rod, by which we measure progression in pitch, as rhythm measures progression in time.'' [1] Now if we observe the progression of the interval through musical history; we will almost always find the intervals of the octave, fifth, and the fourth in all musical scales. It has been said that the origin of all scales can be explained by the assumption that all melodies arise from thinking of a harmony to them, and that scales arose from breaking down the fundamental chords of a particular key. But scales existed long before the experience of harmony and ancient composers had no feeling for harmonic accompaniment, as non-harmonic

scales are far more numerous than harmonic scales. (see table on pg. 2)

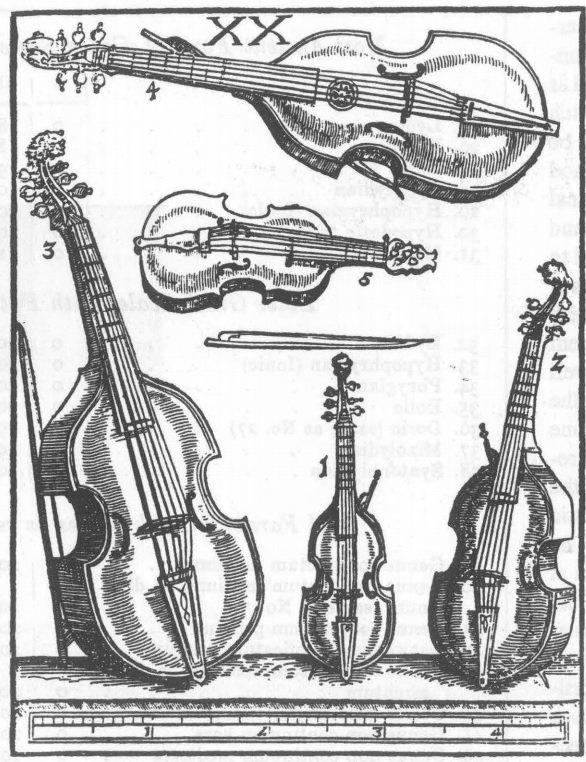

Musical pitch (tuning pitch) has undergone continual change throughout history. Tuning pitch or the tuning note is here classified as the 'A' of the violin from which the pitch number of all other notes in the scale must be calculated from the temperament and method of tuning in use. Now, the pitch of musical instruments has always varied greatly and '' ... since the ancients were not accustomed to play in concert with all kinds of instruments at the same time, wind instruments were very differently made and intoned by instrument makers, some high and some low.' [3] It is well known that for higher instruments such as the mandolin, trumpet, violin, etc., the higher one tunes, ''the more freshly it sounds and resounds. " [3] For the deeper instruments, the lower they are tuned, " ... the more majestic and magnificent is their stately march.' '[3]

The general rise in standard tuning pitch began at the Congress of Vienna in 1814, when the Emperor of Russia bestowed upon his Austrian regimental band new and sharper instruments. This band became noted for the brilliancy of its music, and gradually tuning pitch at Vienna rose from A' 421.6 cycles per second (Mozart's pitch), to A' 456.1 cps or nearly three quarters of a tone. As far as recorded

history is concerned, standard pitch has undergone-changes from Delezenne's A' 373.1 cps (1640?) to Steinway's orchestral pitch of A'

460.8 cps (1880) and seems to have stabilized at around A' 440 cps today.

It is now apparent that there are many modifications of interval relationships, intonations and standards of pitch pertaining to the art musical. These anomalies do have a remarkable influence on whether or not each particular key in music possesses its own

individual character. One must understand, however, that only specific instruments will allow for the distinction between keys. If we

were to choose an instrument of fixed tones . with uniform tuning, and magnitude (such as the synthesizer and other electronic instruments usually of the keyboard type) one could not distinguish between the absolute character of keys. On the other hand, there is a decidedly

contrasting character in the disparate keys on stringed instruments which the following experiment may reveal. If we take two different

instruments, tuning one in such a fashion that its D flat is the same as the C major of the other, we will notice that on both instruments the C

major retains its brighter and bolder character while the D flat remains soft and veiled. This is of course due greatly to the differences in the

quality of tone of strings which being stopped at different places on the fingerboard will no doubt alter the intonation in comparison to the

open string's perfect intervals of tuning. Differences of character on wind instruments can be even more striking.

In review of the above material, we can see that all intervals suggested are mere interpretations of approximations due to intonational differences, pitch differences, etc., and no two can really be alike. When we speak of the interval of the fourth, fifth and so on, we are

really speaking of the ideas that these applied titles represent. Our perception of intervals rests solely upon how we divide the octave, be

it into twelve equal parts or one hundred unequal parts as the octave is our only musical boundary. The definition of intervals can only

be limited according to esthetic and artistic creation. However, whether fortunate or unfortunate, our musical history demonstrates a natural leaning toward a diatonic and twelvetone chromatic system which we as its creators can not ignore.

The real experience of the interval is most appreciated by our thoughts, feelings and by our spiritual being. Music can reflect such sundry and diverse characters of motion as ''Graceful rapidity, quiet advance, grave procession, and wild leaping, ... and as music expresses these motions, it gives an expression also to those mental conditions which naturally evoke similar motions, whether of the body and the voice, or of the thinking and feeling principle itself.' '1 As thoughts and feelings march.. about, so do the melodic motions of tones, by imitation and expression. We may deal with the multifold complexion of motion in music at a later time but, for now, let us deal with our awareness of consonant intervals.

The true feeling for the octave has really not yet been developed in humankind. As one may perceive the differences that exist between intervals up to the seventh in relation to the tonic, one cannot actually discriminate between the octave and the tonic on a spiritual level. We simply do not use the octave in the same manner as the other intervals. Although, we can certainly distinguish the difference between the tonic and its octave by difference of frequency, we have not yet acquired its feeling, and this will be developed in time. '' ... in the future the feeling for the octave will be something completely different, and will one day be able to deepen the musical experience tremendously, ... and will become a new form of proving the existence of God.' [4]

Returning to an earlier period in human evolution, all musical experience (according to Steiner) saw its fifth development in the Atlantean age with the experience of the seventh (these concepts will start to make more sense as the other intervals begin to unfold). If we could go back to this age, we would find that the music, having little resemblance to today's music, was arranged according to continuing sevenths and all other intervals were absent. This experience, which has become an unpleasant effect as of the post-Atlantean era, was based on the interval of the seventh through the full spectrum of octaves and gave one the feeling of transportation from our earthbound existence. This feeling of the seventh eventually became somewhat offensive and was replaced by the feeling of the fifth as the human being wished to incarnate more deeply into the physical body.

Music that progresses in fifths is actually still connected to the transported feeling of the seventh by experiencing motion outside of physical organisation. This becomes more evident when we take the scales through the range of seven octaves and realise that it is possible for the fifth to manifest itself twelve times within these seven scales. This, of course, has always been considered a Pythagorean invention for it has been stated (historically) that he constructed the whole diatonic scale from this series of fifths thusly;

and calculated all intervals from the above scale. The fact is, the Greek scale was actually derived from the tetrachord, or divisions of the

fourth. If we proceed upwards from C by fourths, we obtain:

Abb Dbb,

and if we continue downwards we get:

The notes after Gb in the first series, are actually:

and are the same as those related to by Abdul Kadir, a celebrated Persian theorist of the fourteenth century. This system can be seen throughout the whole Arabic and Persian musical system which seems to have developed before the Arabian conquest, and " ... shews an essential advance on the Pythagorean system of fifths. "[1] (Note that the Arabic lute is tuned in fourths.) All of this is really only important for its historical significance in reference to our interval experience.

In the earlier music of the fifths, the human being felt lifted out of the physical. We still find remnants of this in the pentatonic scales of the Chinese and the Gaels. Many of the ancient Chinese, as well as Scotch and Irish tunes have neither a fourth nor a seventh in them. As far as the these Celtic melodies are concerned it maybe of some interest that early bagpipes (upon which, most of this music was composed) were constructed without these two intervals. In most of their melodies, the omissions in both major (the 4th and the 7th) and minor (the 2nd and 6th) scales are so premeditated as to avoid the intervals of a semitone, and are replaced by intervals of a tone and a half (see below). This, of course, gives the music a certain quality which may indeed give one the feeling of being transported to the 'Land of Fame'.

With our experience of the fourth, we may reach out to the forgotten self in the spiritual sensations of the fifth, and also return inwardly to our inner being in the experience of the third. Our common 1-4-5 progression exhibits this border phenomenon of the fourth. In the experience of the fourth, we may move about between the spiritual and physical worlds. The sixth also expresses this border sensation

only on a higher level.

Now we may come to the most significant experience.in the interval of the third. Something new appears with the arrival of the experience of the third. Now we can encounter the feelings aroused by major and minor keys. With the third we can color the musical entity with mood, and this displays for us the inner life of feeling. This is the predominant experience of the present age, or the age of introversion. As the more inward element tends toward the minor side, the more outward element tends toward the major side. If we consider the seventh's role in our present age, we see that minor and major sevenths tend to rule composition in what is considered popular music. This appears to be the channel of enslavement most have come to accept, although it is not an eternal predicament

The perception of the interval of the second establishes the intensification of our inner life, and this is only a recent experience. It is usually only encountered under the guise of the ninth chord which brings us to an interesting conjecture. In ancient traditions our sevenfold nature is referred to quite often. Spiritual experience of that age had developed in part from the observation that the number of planets in the solar system corresponded to the seven scales and that the twelve signs of the zodiac equalled the twelve fifths of the seven scales. But, a disturbing revelation came with the changeover from the ancient geocentric system of seven planets to the modern heliocentric system of nine,rendering the system of correspondences imperfect. One may see the blooming of our technological and materialistic age from a galloping (or should we say hobbling?) science of discovery taking shape in some of the more recent musical trends as well. Discovery without regard to spiritual interpretation may not always be such a good thing.

In conclusion, we can view the whole of the experience of the intervals from Rudolf Steiner's graphic depiction as seen above. Since 3 and 4 overlap, as well as 6 and 7, Steiner has cleverly arrived at the human being's sevenfold nature through a ninefold organisation.

'The facts of human evolution are expressed in musical development more clearly than anywhere else.'

1. Hermann Helmholtz. On the Sensations of Tone, New York: Dover, 1954.

- William Chappell. Popular Music of the Olden time, Volumes I and II, London: 18??

- Syntagmatis Musici, Michaelis Praetori C., Tomus Secundus, de Organographia, 1619.

4. Rudolf Steiner. The Inner Nature of Music and the Experience of Tone, Anthroposophic Press, 1983. - Michael Theroux. Back to Bach, Journal of Borderland Research: May-June, 1988.

- H.A. Clarke. Pronouncing Dictionary of Musical Terms, Theodore Presser Co., 1896

- Thomas Morley. A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke. 1597.

This article was sourced from the Journal of Borderland Research Vol XLVII, No.5 September-October 1991

Download the full volume here: http://bit.ly/2kq3qQP

Download a collection of the Journal of Borderlands Research here: http://bit.ly/2L5cGWo

Michael Theroux’s Website: https://michaeltheroux.com/

Free Book “Rhythmic Formative Forces of Music” by Michael Theroux : https://michaeltheroux.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/rff.pdf