The Antimatter Factor located at the European Nuclear Research Centre (CERN) in Geneva is the premier factory for making the most expensive atoms, by weight, on the planet. In fact, it is the only place in the world where antiatoms are created on a daily basis.

This blog series is aimed to inform the general public on the subject of antimatter, based on what happens in the Antimatter Factory at CERN, including the antimatter production, as well as the experiments performed. This series will take you inside the building with pictures and descriptions of the most important equipment and machinery.

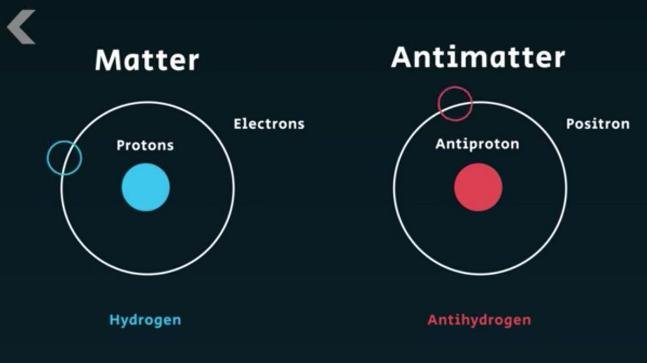

Antiparticles are especially slippery test subjects. With the same mass but the opposite charge to ordinary particles, they disappear in a puff of energy (annihilation) whenever they meet normal matter, which makes up everything we see. That means antiparticles have to be meticulously made and captured for each test.

Antimatter was first predicted to exist in 1928 by Paul Dirac, who found an equation combining quantum theory and special relativity to describe how electrons move at relativistic speeds. The equation resulted in two possible solutions, one for an electron with positive energy and another for negative energy. It was not until 1932 that experimental evidence of the anti-electron (positron) was discovered by Carl Anderson.

Moving and trapping antiprotons or positrons is easy because they are charged particles. But when you combine the two you get neutral antihydrogen which is far more difficult to trap so a special trap which considers that it is a bit magnetic is used.

An atom of antihydrogen consists of an antiproton and a positron (an antielectron). Creating antihydrogen depends on bringing together the two component antiparticles, antiprotons and positrons, in a trapping device for charged particles. One of the difficulties in making antimatter is the energy the antiprotons possess when they are first made, shooting out of the apparatus at close to the speed of light.

Credit: popularmechanics.com

As a result, at the Antimatter Factory, there is no need for speed because the six experiments in this building are not trying to create collisions. Instead, they are slowing antiparticles down enough to carry out experiments – often on a single atom. The complex consists of the Antiproton Decelerator (AD), the Extra Low Energy Antiproton (ELENA) ring and six different experiments.

The pay-off stands to be huge. Ordinary matter and antimatter are expected to behave the same way – responding identically to gravity, for instance. If they don’t, it could be the calling card of exotic new forces, beyond those described by the standard model and Einstein’s general relativity. There are six experiments which study antimatter, all aiming to carry out surgically precise measurements on antihydrogen.

Up next: Part 2 - Why investigate antimatter?

#steemstem #science

Why is then the anti-property attributed to charge and not to mass/energy? Could a positron be a negatively-charged negative mass particle?

And another question:

Are there going to be experiments to test a gravitational mass of antimatter on this factory?

The consensus among physicists is that antimatter has positive mass and should be affected by gravity just like ordinary matter. There are currently two experiments in the antimatter factory which are investigating the effect of gravitational force on antihydrogen, GBAR and ALPHA-g, which I will write about in future blog entries.