If you were wondering what a mottled sculpin looks like, there are plenty of pictures available online. But while they may satisfy a curious tidepooler, the discerning ichthyologist demands more. That’s why a professor at the University of Washington is getting full 3D scans of every fish in the sea — every species of fish, anyway.

With a $340,000 CT scanner, a few lab assistants and a whole lot of fish, Adam Summers wants to build a complete catalog of the more than 25,000 types of fish out there. This isn’t some new mania: he’s been scanning fish since the 1990s, and knows the scientific benefits of this kind of data.

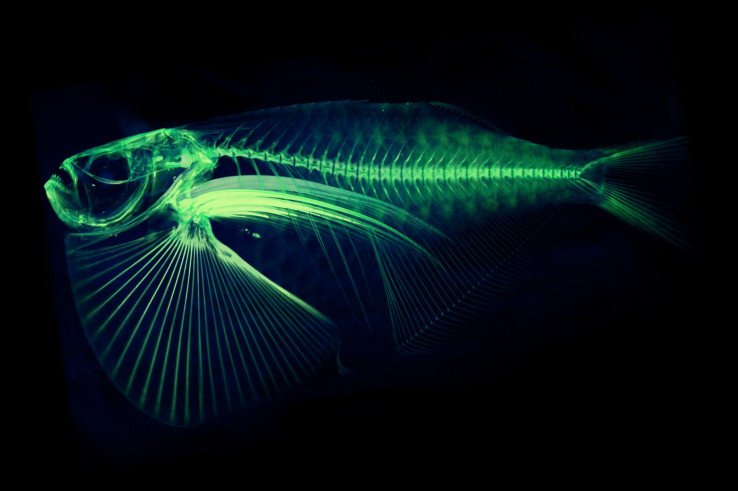

Having digital models accurate to (say) the millimeter allows for instant, exact comparisons between species, or among several of the same species — you could even 3D print a skull, tail, vertebra or whole fish to compare with a real-world sample. It’s an invaluable tool, which is why Summers has made sure that all the data his lab produces is freely available.

“Having this scanner has made it clear to me the incredible power of this system if you think about it the right way,” Summers said in a UW news release. “These scans are transforming the way we think about 3-D data and accessibility.”

The lab is on San Juan Island in the beautiful Puget Sound region of Washington, and Summers now has visitors to his watery paradise who want to scan their own fish. Not folks who just caught a big one, of course, but biologists and museum curators who want to digitize their own extensive collections.

Summers thinks it’ll take between two and three years to scan them all, but that doesn’t mean his work will be over. Next he plans to scan the remaining 50,000 or so vertebrates on Earth — a considerably bigger task in several ways.

So far there are somewhere north of 500 species of fish scanned, which you can browsehere at the Open Science Framework. All the files are the full resolution and free to download.