image credit

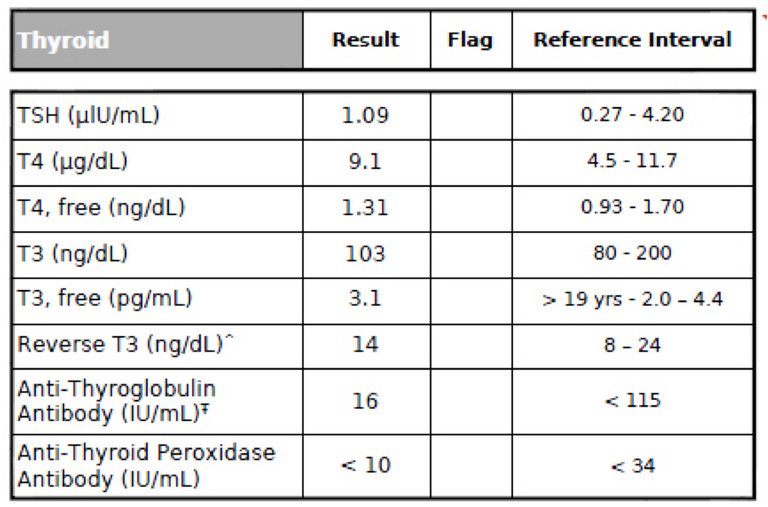

There is an ongoing issue with diagnosing thyroid problems through lab panels, that only very recently has been addressed. Diagnosing tests prescribed by most doctors are incomplete and often lead to an ineffective treatment.

The reason behind this issue is that the thyroid functions through several steps. It is simply not enough to diagnose that the thyroid gland malfunctions or that the thyroid hormone levels in the body are not within the normal range. One needs to identify which exact step malfunctions and why.

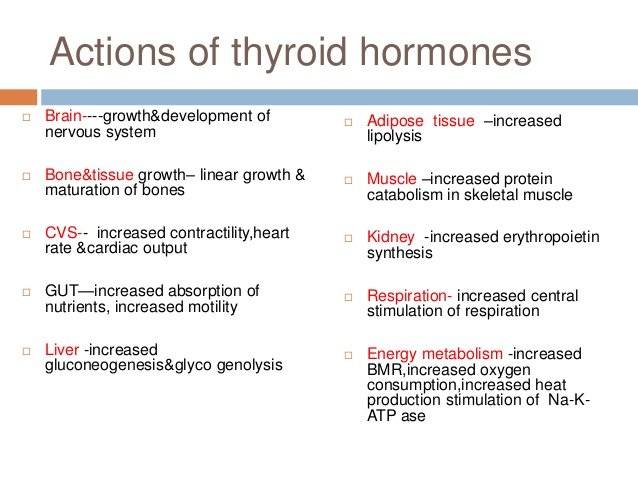

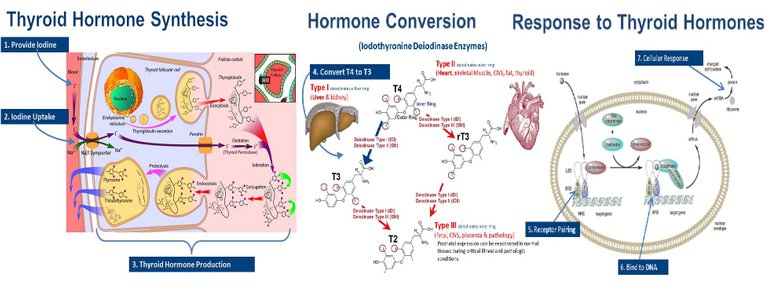

What the thyroid gland does is take iodine from food, combine it with an amino acid called tyrosine, and convert it into thyroid hormones thyroxine T4 and triiodothyronine T3. Their names come from the number of iodine atoms they contain: T4 contains four and T3 contains three.

These are released in the bloodstream, where they control metabolism and almost every physiological process in the body.

image credit

Thyroxine and TSH

Now here comes the tricky part:

The thyroid gland produces much more T4 than T3. Literature does not agree on exactly how much more; Different research and average patient data range from a ratio of 17:1 to a ratio of 3:1.

However, T3 is about 4 times “stronger” than T4. As soon as T4 reaches the organs, it is converted to T3. Therefore, T4 is actually the inactive form of thyroid hormone. It must first be converted to T3 in order for the body to be able to use it. The active form of thyroid hormone is therefore T3.

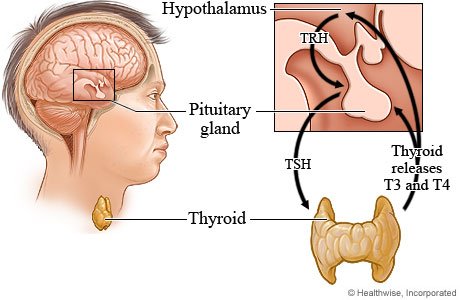

T4 and T3 levels in the body are both regulated by thyroid stimulating hormone, or TSH for short, which is produced in the pituitary gland, found at the base of the brain. The pituitary gland itself is controlled by our hypothalamus, through thyrotropin releasing hormone.

image credit

TSH release stimulates the production of T4. In turn, the levels of T4 and T3 in the blood dictate the amount of TSH that will be secreted. If there is enough T4 and T3 in the blood, the pituitary gland will decrease the production of TSH, and vice versa.

Thyroid Panel Issues

When suspecting a thyroid issue, most doctors will prescribe a T4 and a TSH panel test only, and base their diagnosis only on these results. This approach is problematic for two main reasons.

- The “normal” range is not so normal:

- This approach cannot identify which process malfunctions:

Apart from the fact that range markers vary from lab to lab and even more so from country to country, these are not actually based on the average markers of the general population, but on the average markers of the people who come to these labs for testing. Taking in consideration that most people order a testing when they already suspect that something is wrong with them, this essentially means that labs create their “normal” ranges based on results obtained from sick people! This means that a patient with mild symptoms is more likely to be dismissed as healthy.

In addition to that, it is important to note that falling within the normal (average) lab range is not equivalent to being within the optimal range required to feel perfectly healthy.

The thyroid physiology is a very complex one and involves several steps. The most basic of these are the following: the hypothalamus stimulating the pituitary gland, the pituitary gland stimulating the production of TSH, the TSH regulating the production of T4, the production of T4 by the thyroid gland using iodine, the conversion of T4 to T3 through the deiodinase system in multiple tissues and organs, the regulation of T4 and T3 levels by the TSH, the production of transport proteins produced by the liver, their transportation through the blood and eventual detachment of the protein carriers, and their binding to thyroid hormone receptors in the cells.

image credit

A malfunction in any of these steps will cause a different set of symptoms and a significant variance in lab test results. Hypothyroidism (as well as hyperthyroidism) are not a single illness each with a defined cause and course and potential issues are not exclusively located in the thyroid gland. It is therefore incorrect to assume that they will all show up in the same way on lab tests.

What should a complete thyroid panel include:

- T3, T4 and TSH:

- FT3 and FT4:

- Reverse T3:

- Antibodies:

- Vitamin Deficiencies:

The levels of certain vitamins and minerals which are highly associated with thyroid function, such as iodine, selenium, vitamins B, D and several others, need to be tested in order to determine whether: a) deficiency of a certain vitamin or mineral is causing a thyroid issue or b) a thyroid condition is itself causing deficiencies in specific vitamins or minerals There will be more about deficiency correlations on a next article.

It is important to keep in mind that apart from blood work analysis, there are other testing methods which can aid a correct diagnosis. These include an ultrasound, in which the thyroid can be examined physically, as well as a CT scan. A damaged thyroid seen in an ultrasound test certainly confirms that something is wrong with the thyroid gland, even though lab tests fall within the normal range.

Testing only T4 and TSH is simply not enough. As we mentioned above, T4 is the inactive hormone and is not really useful if it cannot get converted to T3. Even if tests show that the levels of T4 are within the range, the levels of T3 also need to be tested. Furthermore, in order to obtain a more objective understanding of the thyroid function, T4, T3 and TSH need to be analysed together, as low levels of one and high levels of another indicate different causes.

For example, high TSH, low T4 and either normal or low T3, usually indicate primary hypothyroidism, which means the issue lies within the thyroid gland itself. Slightly low TSH and slightly low T4 (which could still be within the lab range) indicate pituitary dysfunction caused by elevated cortisol levels due to infection or blood sugar imbalances, while normal TSH and T4 levels and low T3 levels indicate issues with the conversion of T4 to T3, again often caused by inflammation and elevated cortisol levels.

Unfortunately, several issues with T3 are categorized by many physicians as “non-thyroidal illness”, as their basis is not the thyroid gland itself, and are not examined in standard thyroid tests. This is a problematic approach because, as we will see below, thyroid processes and functions within the body are all interconnected.

Apart from testing the amount of total T4 and T3 in the blood, a more useful measurement is to test the amounts of “free” T4 and T3 (FT3 and FT4). While “total” refers to the total amount of T4 and T3 circulating in the blood, it includes hormone that is bound to protein, which makes it inactive. “Free” hormone is the amount that is unbound and active. It is therefore useful to also test the levels of the protein that transports the thyroid hormone though the blood. This protein is called thyroid binding globulin, or TBG for short.

For example, if levels of TBG are high, the levels of unbound (free) protein will be low. The lab tests will show TSH, T4 and T3 levels to be normal, while free T3 will be low and TBG will be high. This imbalance is often caused by elevated estrogen levels. Inversely, when TBG is low, free T3 will be high. Again, TSH, and total T4 and T3 levels will show nothing wrong. This imbalance is caused by high testosterone levels or insulin resistance.

image credit

Additionally, low FT4 indicates secondary hypothyroidism. This a rare condition in which either the pituitary or the hypothalamus malfunctions and not enough TSH is secreted. In this case, the thyroid gland is functioning properly but does not receive enough TSH to signal the production of T4 and T3.

As mentioned above, T4 contains four atoms of iodine while T3 contains three. When an iodine atom is removed from T4, it turns to the active form of T3. The thyroid gland itself releases 90% of its hormone as T4, 9% as T3 and only 0.9% as rT3. However, almost all rT3 in the blood is made somewhere else in the body, where enzymes remove a particular iodine atom from T4.

Just as T3, Reverse T3 has three iodine atoms and many doctors believe that rT3 is an inactive metabolite with no significant effects. However, reverse T3 is made when the “wrong” iodine atom is removed from T4. Increased levels of rT3 result in blocking T3 receptors and preventing its absorption in the body. This essentially means that even if all lab tests of TSH, T3 and T4 levels fall within the normal range, the body does not respond properly to T3 leading to hypothyroid symptoms. This condition is called “tissue resistance to thyroid hormone” or simply “tissue hypothyroidism”. Since ranges vary from lab to lab, it can be best diagnosed by calculating the ratio of Free T3 to Reverse T3. If the ratio is less than 20:1, it indicates a possible problem. A high FT4 reading is also a marker for potential high rT3.

image credit

High levels of rT3 are often caused by sudden or extreme dieting, as it slows down metabolism in order for the body to use all available food! It can also be caused by cortisol or insulin imbalances, low ferritin or low B12 levels.

In the case that the condition is autoimmune, such as with the case of Hashimoto’s or Grave’s disease, the body also produces anti-thyroid antibodies. The main thyroid antibodies consist of anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies (anti-TPO for short), thyrotropin receptor antibodies (TRAbs), thyroglobulin antibodies and anti-sodium/iodide symporter antibodies. A complete panel should include antibody testing to either identify or rule out autoimmune conditions, as these require different treatments!

For example, 90% of the patients with the autoimmune condition Hashimoto’s have elevated anti-TPO levels. Even if their TSH, T3 and T4 levels are still normal, a patient with elevated TPO antibodies most likely has Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. TPO antibodies attack the thyroid gland, destroying its hormone-producing cells and eventually causing hypothyroidism. There will be more information on thyroid antibodies on a next article.

excellent job