After years of working with reptiles, I have learned something: turtles and tortoises are just weird animals. They have an iconic shell that is unlike anything in the animal kingdom. Their bizarre skeletal structure greatly impedes their range of motion and movement speed. They have a completely unique type of skull from all other vertebrates. They are largely dim-witted animals (with a few exceptions). And yet, turtles and tortoises are among the most successful species on the planet. Of course, most of their success is in large part due to their incredible shells (which is also just weird).

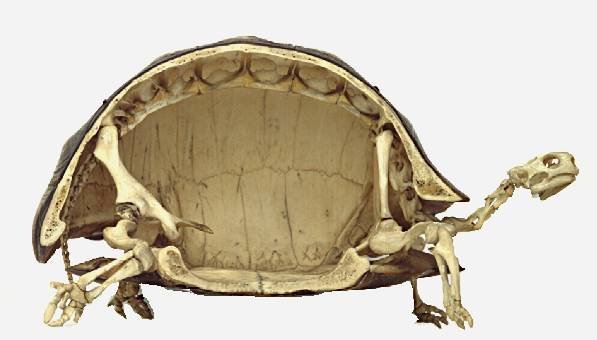

The shell of a turtle is an interesting structure that is essentially just an augmented rib cage. The individual ribs of the shell are flattened and expanded to the point where they have fused with one another, creating the bony carapace. The shell is then covered with large keratin scales that we call scutes. This is why turtles cannot leave their shells like a hermit crab as depicted in cartoons; unlike a crab, the turtle's shell is part of its internal skeletal structure (if you look at an old turtle shell, you can clearly see the spine embedded in the roof of the carapace). There is no layer of skin beneath the shell either, so if you were to cut into the shell, you would enter the body cavity where the organs are housed; this is why turtles with severe shell injuries are not likely to survive. (It is also worth noting that the shell is comprised of living tissue, so carving into the shell or even painting can have negative effects on the animal, and is largely discouraged).

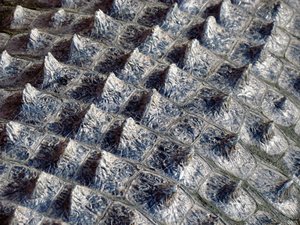

Despite knowing the anatomy of the turtle shell, we are still piecing together exactly how such an interesting structure evolved in the first place. Biologists have debated for over a century how the turtle shell came to be in the earliest testudines; paleontologists argued that early shells formed from osteoderms, bony-plate scales (found in the armor of crocodilians, armadillos and some dinosaurs) that eventually grew and fused with the ribs and backbone to form a crude shell. Developmental biologists disagreed, suggesting that the shell simply was the result of the ribs broadening and eventually fusing. Unfortunately for the debate, the oldest known turtle was a fossil called Proganochelys, but because it already had a full developed shell, it didn't offer any clues as to how the structure originally arose. Source

The debate was finally put to rest in 2008 when Chinese researchers made an incredible find: a 220-million-year-old turtle... whose shell covered just its belly and not its back. They named it Odontochelys semitestacea, which literally translates to “toothed turtle in a half-shell", and it was the intermediate fossil that provided the crucial evidence we needed: the very broad ribs and lack of osteoderms were enough to prove the developmental biologists correct. With the discovery of an intermediate, the evolution of shells fell into place with an existing fossil of a 260-million-year-old animal called Eunotosaurus (this animal was previously ruled out as a turtle ancestor because it lacked osteoderms, though it too supported broads ribs and a "half-shell"....it was ignored for almost a century despite its importance!).

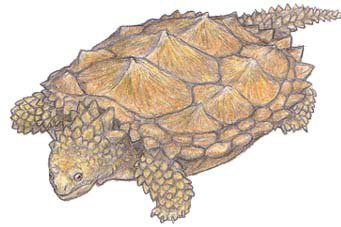

Now declared one of the earliest known turtles, the Eunotosaurus looked like a burrowing lizard "with stocky legs and bulging flanks" (Source). From the fossils, scientists were able to deduce that the lower ribs began growing wider first, eventually fusing to create the lower portion of the shell, the plastron. The upper portion of the ribs developed similarly later on, fusing with the spine and one another to form the upper portion of the shell, the carapace. The skeletal structure then shifted in what some researchers simply call "evolutionary origami"; the ribs began growing OVER the shoulder blades, rather than sitting below them (as is the case for humans and most land-dwelling vertebrates). Source

This answered questions regarding exactly how the iconic shell formed, but it raised new questions. Tyler Lyson (Denver Museum of Nature and Science) began to suspect the shell may have arisen for different reasons than previously thought.

“For me, the next question was: Why? And there are two huge reasons why not.” -Tyler Lyson Source

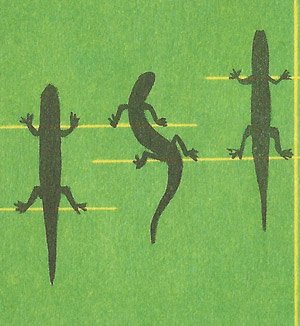

Though it might seem useful, a shell is not the most beneficial structure. The first problem comes with respiration; ribs and their muscles help inflate and deflate the lungs when animals breath. Having enlarged, fused ribs compromises that ability (turtles had to develop a new method of breathing called "buccal pumping" to overcome this). The second problem is it slows you down, and not just because the shell is a heavy structure. Reptiles have sprawled limbs, so when they walk, they bend their bodies back and forth to increase the length of each stride, using the trunk of the body to move along. Because the shell prevents the body from bending, the turtle/tortoise is powered only by its limbs. So Lyson began wondering, "what benefit could a shell possibly provide that compensates for being worse at both breathing and walking?" Source

The answer seems simple at first. If asked why turtles evolved a shell, most people would just assume its a protective structure. But while today's turtles are heavily armored, Lyson had doubts that protection was the original goal of the bony plastron. He pointed out that the wide ribs of Eunotosaurus would have done little to protect the animal as they didn't shield the head, neck or back. He suggests that if turtles really wanted to evolve protection, they would have done so similar to crocodilians, developing osteoderms that wouldn't have had negative consequences for breathing or movement.

Lyson pieced together a hypothesis as he studied a huge number of Eunotosaurus fossils. He took note of several key features; the skull was short and had a shape similar to a spade. Its front legs were larger and sturdier than its hind legs. The shoulder blades and fore limbs had large attachment points for especially large tricep muscles, suggesting that the turtle ancestor could pull its arms back with extreme force. Lyson recognized the signs of a fossorial animal, a creature with a burrowing lifestyle; Eunotosaurus was built to be a powerful digger. He believes this lifestyle is the key to the development of the early "shell"; the expanded ribs would have anchored the limbs as they dug, making them powerful excavators. Source

“Eunotosaurus was clearly digging. The big question is whether the early turtles with partially formed shell—Pappochelys and Odontochelys—were too. This is important to know because they represent the stages in which the shell actually formed.” -Rainer Schoch from the State Museum of Natural History in Stuttgart Source

“The selective pressure to develop protective structures may have come from the slower gait that resulted from the broader ribs,” says Judy Cebra-Thomas, Millersville University Source

Because the ribs decreased their speed, early turtles would have been vulnerable to predation (just imagine today's slow, lumbering turtles without their shells). It would only stand to reason that this increased vulnerability drove the evolution of the shell from a defensive standpoint.

“Ribs are pretty boring. From snakes to whales, they’re pretty much the same because they’re so integrated with breathing. But once ribs were freed from that constraint, they could be selected for a shell.” -Lyson Source

The turtle's shell is an example of what we call "exaptation", a process by which traits evolve for a certain function but are later adapted to serve a secondary function. The shell began as a means of excavation and eventually became a mobile fortress. Another example of exaptation is that of early feathers: originally evolved for warmth or mate signaling, they now allow birds to fly, making flight a sort of "by-product" of their evolution.

“A change in a structure of the body can only provide a selective advantage based on its current abilities, not potential future ones. That’s very important, and not just for understanding the evolution of turtles.” -Cebra-Thomas Source

Simply put, turtles would not have just evolved a shell because they might have needed one down the road. Their evolution was fueled by their current lifestyle, which was that of a fossorial animal. They didn't require protection at that early time, but they did require a means for more powerful digging. It was only because of the evolution of widened ribs that turtles would eventually require further armament. Debate will likely continue on the subject as we continue discovering more intermediate fossils, but Lyson's hypothesis is a strong one that is well-backed by evidence. We have learned so much about the evolution of these animals in just the last decade, who knows what we will discover in the coming years?

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Source

This is an outstanding post. I really enjoyed reading it.

It was informative whilst striking the right balance of not going into too much technical detail which might put the casual reader off. Further it illustrated a your passion for the subject in a way that was highly engaging.

One of the best posts I have read in a while and I learned something new.

I always assumed the shells were there for protection from the beginning and had never imagined that digging might have something to do with their origin.

Thank you for sharing this.

Thank you! There's lots of interesting stuff like this out there but you are totally right: there's so much technical detail it just gets muddled up. Most of the education I do at work is just trying to take stuff like this and regurgitate it in a manner that makes sense to people with no science background.

Really interesting stuff.

I was hoping somebody could explain how the incremental changes you discuss give a "survival of the fittest" advantage along the way. I can see how digging holes faster would be advantageous if you were digging them while under attack. But, whether it takes 1 hour or 2 hours to dig a burrow doesn't seem to explain why evolution would head in that direction - since evolution has no look-ahead engineering capability, every incremental change must pay for itself.

What was it about sacrificing mobility today that would select for digging or defense or anything else in the future?

What did all the disadvantaged unfit generations of turtles do to survive while waiting for evolution to "develop a new method of breathing called "buccal pumping" to overcome this" restriction on ability to breath? How many simultaneous modifications did it take to create this new method of breathing before it became functional and what selected for each of those intermediate modifications that added no advantage until they were all complete?

Thank you and good questions. They didn't just sacrifice their mobility off the bat for the digging benefits down the road. They were already a fossorial species, and probably modestly adapted for that life-style. Their ribs began shifting and widening to serve as forelimb-anchors because that fit well with that particular lifestyle. The trade off was that it did make them slower, however since they spent the large amount of their time underground, speed was not the most pressing issue (it wasn't until turtles took to the water that we believe they started to compensate for their slow speed by developing a protective shell). So yes, they did sacrifice their speed, but it was to increase qualities that made their immediate life easier.

Buccal pumping probably evolved alongside the ribs. We still don't know exactly how that method of respiration arose (it's still up for debate) but it probably developed as the ribs were expanding and making normal respiration more difficult. I think it will be a while before we have an answer to that question.

Very interesting article, now I have some turtle shell evolution knowledge up in my noggin' :D

You'll be the life of the Christmas party with all that knowledge!

I had no idea there was no layer of skin between the shell and the turtle's body. And after reading this, it makes sense that prehistoric turtles had to dig. They aren't fast enough to out run predators so evolution could have really gone two ways: burrow or fly. Fascinating stuff. Thank you. :)I love your articles @herpetologyguy. They are so packed with interesting facts that one doesn't realize there is learning involved.

Thanks for the support!

There was so much information, it couldn't all be packed into one post. You're absolutely right, turtles did start burrowing for protection, but it wasn't fear of predators that drove them underground. Fossil evidence suggests that these turtles live in an incredibly hot and dry climate (hence why they didn't take to the water earlier) and they began burrowing to escape the intense midday heat. It's astounding to think the whole concept of the shell originally stemmed from a turtle just trying to get out of the sun for a bit!

WOW, no kidding? It makes sense about the temperatures too. I read somewhere, albeit a long time ago so my memory may not be good, that animals in the desert would dig what I call a "butt hole" (LOL) only a few inches deep as it's approximately 10 degrees cooler and gives them a respite from the midday heat.

This is easily the best thing I've read here on Steemit. Fantastic work!

Thank you! That is high praise!

Really excellent educational content, very well presented.

Incredible!

Turtle's Shell Wasn't for Protection!

interesting article

Thank you!

We were at the AMNH in New York this past summer and saw some turtle shells that were as big as a table -- 6 feet across or so. http://www.amnh.org/science/divisions/paleo/bio.php?scientist=gaffney

I need to visit! I believe they have a shell of Stupendemys (monster-size freshwater turtle)!

another interesting post - quite amazing how they have developed

love that 1/2 tortoise picture - really shows what you are saying.

thanks for the share

Thanks! They're such weird animals, it's hard to visualize without a skeleton!

Interesting and well crafted post. This is exactly the quality of content I hope to see here as a result of the free market of ideas and information.

Very informative, glad to have learned something new from you.

I like turtles